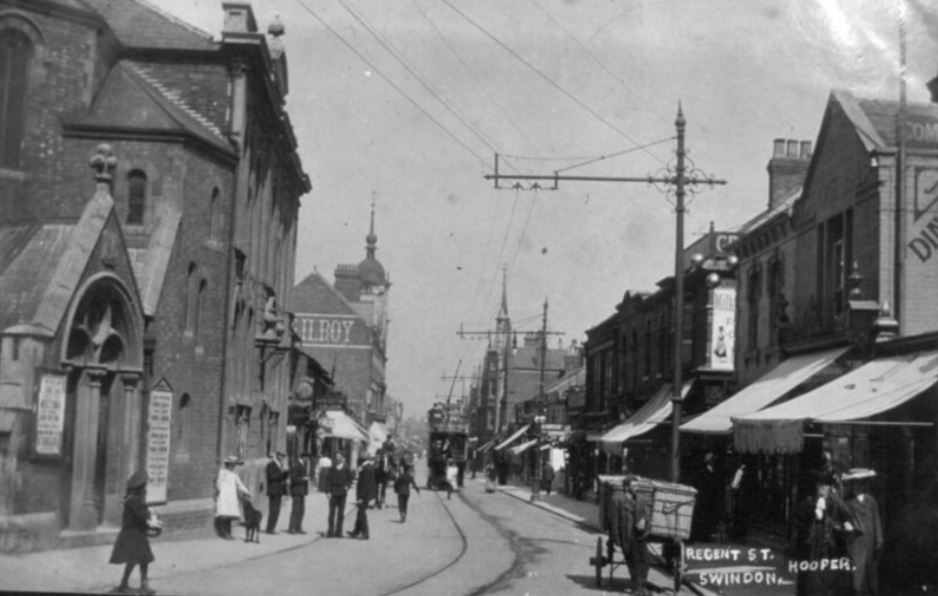

Princess Helena Victoria visited Swindon on April 21, 1923 published courtesy of Local Studies, Swindon Central Library.

The re-imagined story …

When I told mum the Mayor had selected me to meet Princess Helena Victoria when she came to Swindon, she said nothing at first.

I joined the Girl Guides when I was 12 and went on to become a Ranger. It was in this role that the Mayor, Cllr Harding, had invited me to meet the Princess when she came to town to open the Boys’ Red Triangle Club.

I loved everything about being a Guide. I loved the fellowship and the feeling that I was making a contribution to society. I had made some good friends. Where we met was the only place I could relax and have fun and laugh and be myself. There wasn’t much laughter in our house. Mum’s grief was all consuming, to laugh seemed to be making a mockery of her sadness.

She hadn’t always been a serious kind of person, it was dad who was the sombre character. She would tease him and tickle him when he refused to smile and I can hear her tinkling laughter somewhere in my memory.

“I’d rather you didn’t meet her, Sylvia.”

I was stunned. The Mayor had paid me a huge honour, selecting me to meet the Princess.

“It’s a real privilege mum. The Mayor has only asked George Akins from the Scouts and me to meet her.”

“She’s German,” said mum, blunt just like that. ‘She’s German.’

“She’s Queen Victoria’s granddaughter.” I was incredulous.

“And she was German, too. I’ll not have a daughter of mine shake hands with a German.”

I couldn’t argue with her, that would have been too cruel. She had lost dad and my uncle in the war. Sometimes it felt as if the war had been in another age, at other times it felt as if we were still living through it. Some people would bear the scars for a lifetime, limbs lost, faces disfigured, minds broken. My mum had a broken heart and I doubted whether she would ever recover.

Everyone was excited about seeing the Princess. There was to be a luncheon at the Queen’s Royal Hotel first before she opened the Boys’ Red Triangle Club and a Civic Gathering in the Town Hall afterwards.

I explained to the Mayor why I couldn’t greet the Princess. I thought he would be angry, but actually he seemed to understand.

Sometimes it felt as if the war had been in another age; at other times it felt as if we were still living through it.

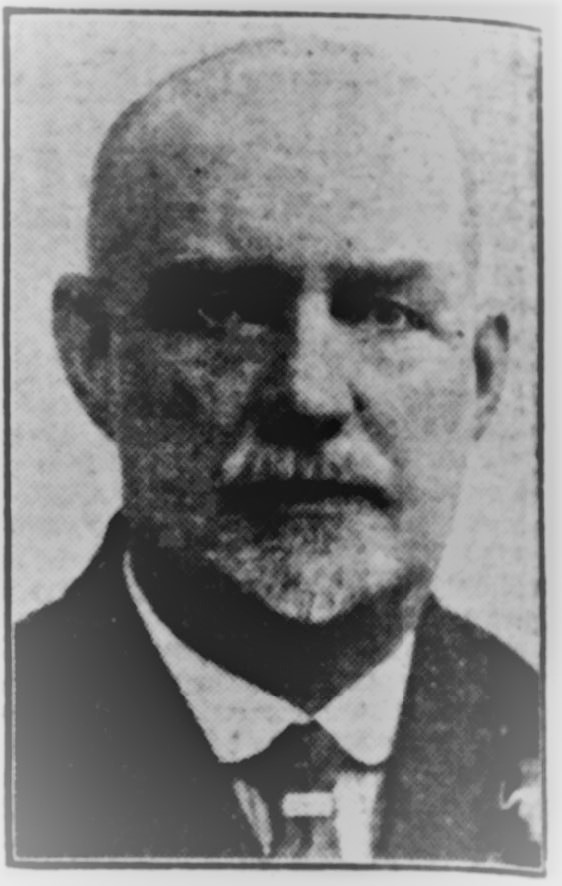

Mayor A.E. Harding

The facts …

Princess Helena Victoria visited Swindon on Saturday, April 21, 1923. The Princess was the elder daughter of Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein and Princess Helena, the daughter of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. She was born at Frogmore House in 1870 and lived her entire life in Britain. During the First World War she visited British troops in France and afterwards worked to promote and support the YMCA and the YWCA. During the war King George V relinquished the use of German royal titles for himself and his numerous cousins.

Albert Edward Harding was born in London in 1865. At the time of the 1881 census he was working in the railway factory as a clerk and lodging with the Hunt family at 38 Prospect. He married Agnes Westmacott in 1889 and the couple had three children, Stewart Jasper, Myrtle Marion Westmacott and Albert Edward Benjamin Harding.

The family first lived at 115 Princes Street where in 1898 Harding was the divisional secretary to the National Deposit Friendly Society, in addition to his job as a Clerk in the railway works. The family later moved to their long-time home at 56 Victoria Road.

Albert Edward Harding was a Councillor representing the East Ward from about 1911 and served as Mayor of Swindon in 1922/23, the year that Princess Helena Victoria visited Swindon.

Albert Edward Harding died at his home on December 30, 1943. He is buried in plot E8568 with his wife Agnes, their son Albert Edward Benjamin Harding and daughter in law Kathleen.

Their eldest son Stewart Jasper Harding is buried in the neighbouring grave plot E8569 with his wife Gladys.

You might also like to read