The Stanier family were railway royalty in Swindon.

William Henry Stanier entered the services of the Great Western Railway on November 7, 1864 in the Managers Office, Loco Works, Wolverhampton. He moved to Swindon in 1871 at the insistence of William Dean, Chief Locomotive Engineer and became Dean’s clerk and personal assistant, and became his right hand man. In 1879 he was appointed Chief Clerk Loco & Carriage Department and in June 1892 he was made Stores Superintendent. His son, William Arthur Stanier had a prestigious railway career. He became Assistant Works Manager at Swindon in 1912 and then Works Manager in 1920 before being head hunted by the London Midland and Scottish Railway where he became the Chief Mechanical Engineer. He was knighted on February 4, 1943.

But did you know that William Henry’s brother, Henry Alfred Stanier, also left Wolverhampton and moved to Swindon?

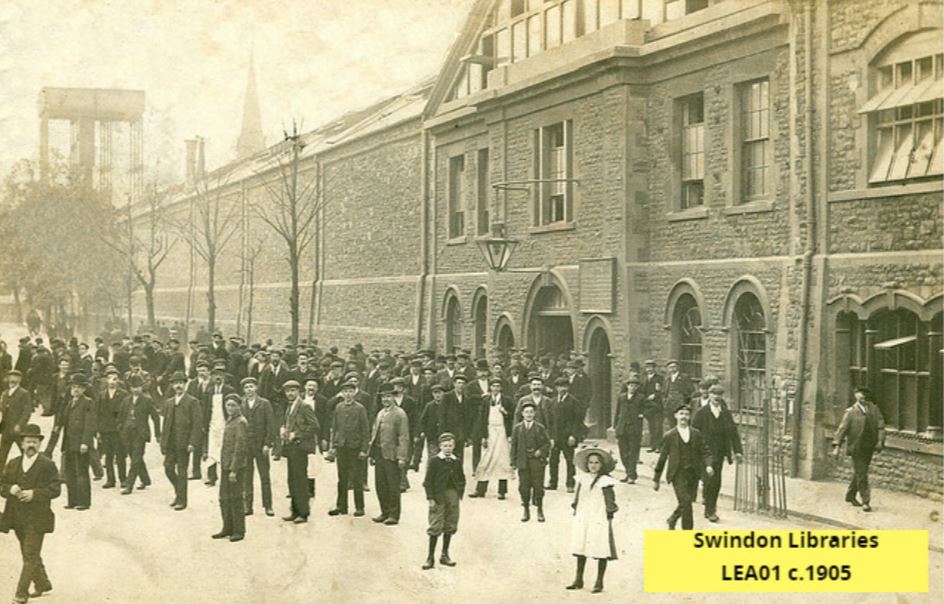

Photograph of Henry dated 1873

The third of Thomas and Ann’s four sons (they also had a daughter), Henry grew up in Wolverhampton. By 1871 the two elder sons, Thomas and William, were working as railway clerks while 18 year old Henry was a Canal Carriers clerk.

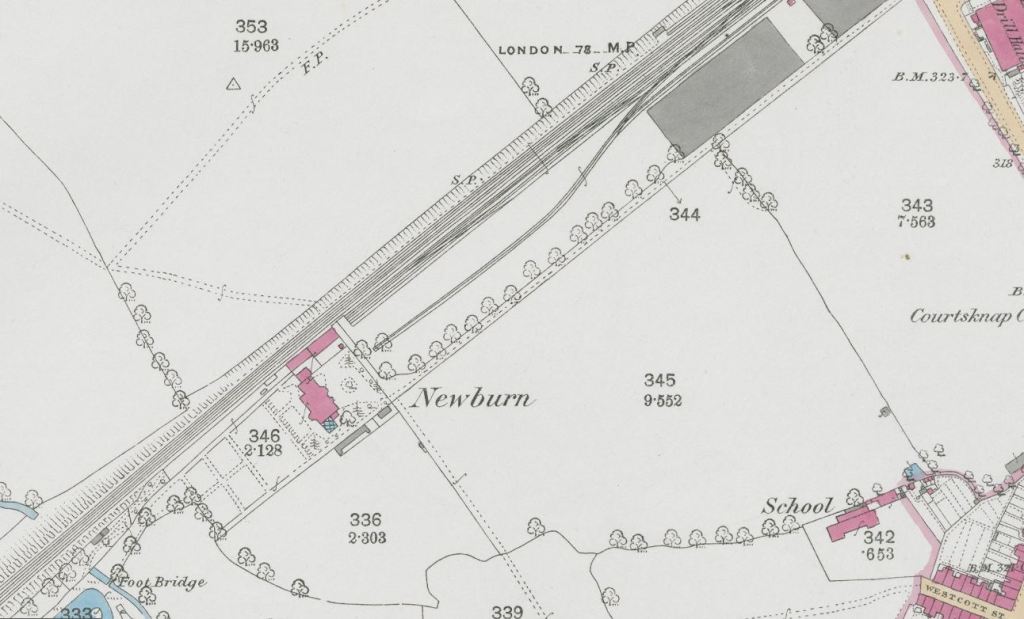

He married Caroline Annie North on January 21, 1879 and soon after moved down to Swindon. His employment records state that he re-entered the Great Western Railway employment on May 4, 1882 as a clerk in the Wagon Department, Manager’s Office. By 1901 the family were living at 12 London Street where Henry remained until his death in 1930.

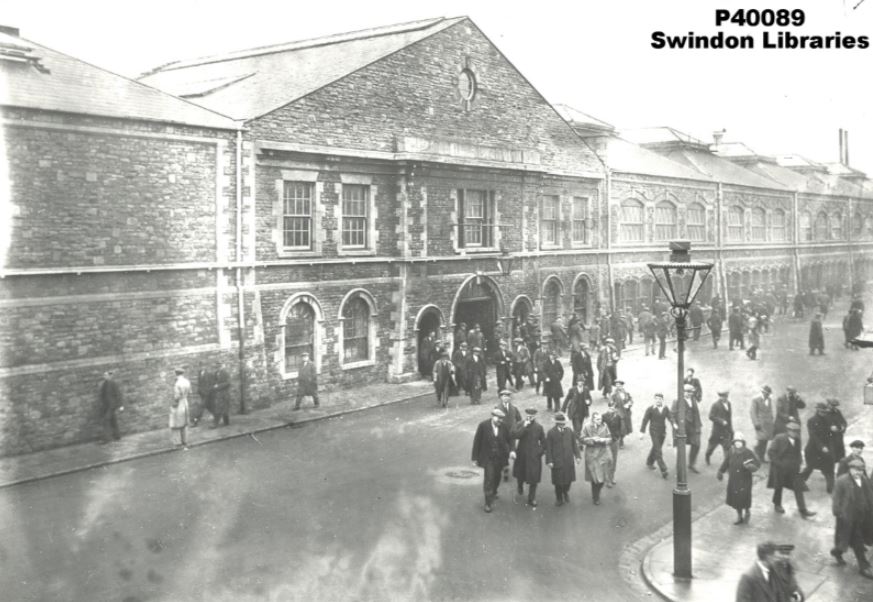

Caroline Anne Stanier nee North – Henry Alfred’s wife

And I made a lucky find on Rootsweb – a photograph taken of the Stanier family outside William Henry’s home, Oakfield, Bath Road, Swindon, dated 1888. The four Stanier brothers are pictured as follows: seated left – Charles Frederick, standing – Henry Alfred, seated middle – William Henry and seated right – Thomas William.

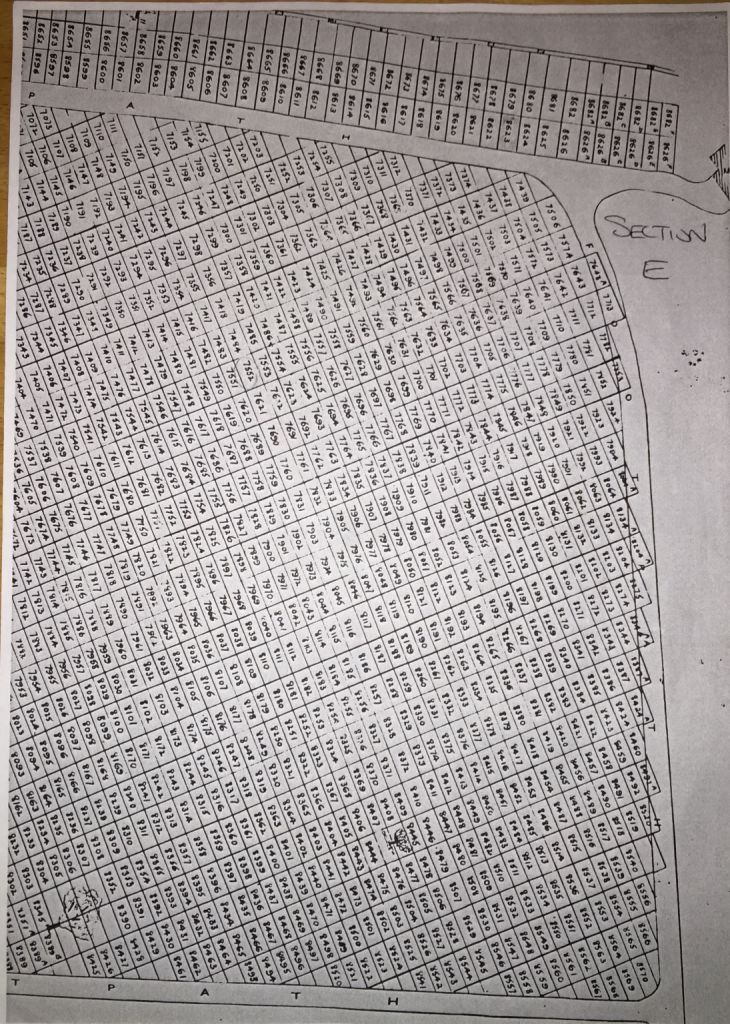

Henry died on February 7, 1930 was buried in grave plot C1886A. His wife Caroline joined him there when she died just six months later.

The death occurred at Swindon, on February 7, at the age of 77, of Mr. H.A. Stanier, who, at the time of his retirement from the Company’s service, in May, 1917, was chief clerk in the carriage and wagon department. Mr Stanier took a keen interest in local affairs, and especially concerned himself with Poor Law administration. He will be remembered for much devoted work for the welfare of the inmates at the Stratton Institution. Mr. Stanier also took an active part in the work of the Mechanics’ Institution and the adult school movement.

Great Western Railway Magazine March 1930.

Henry and Caroline’s grave before our volunteers got to work