Continuing the story of the extraordinary William Greenaway …

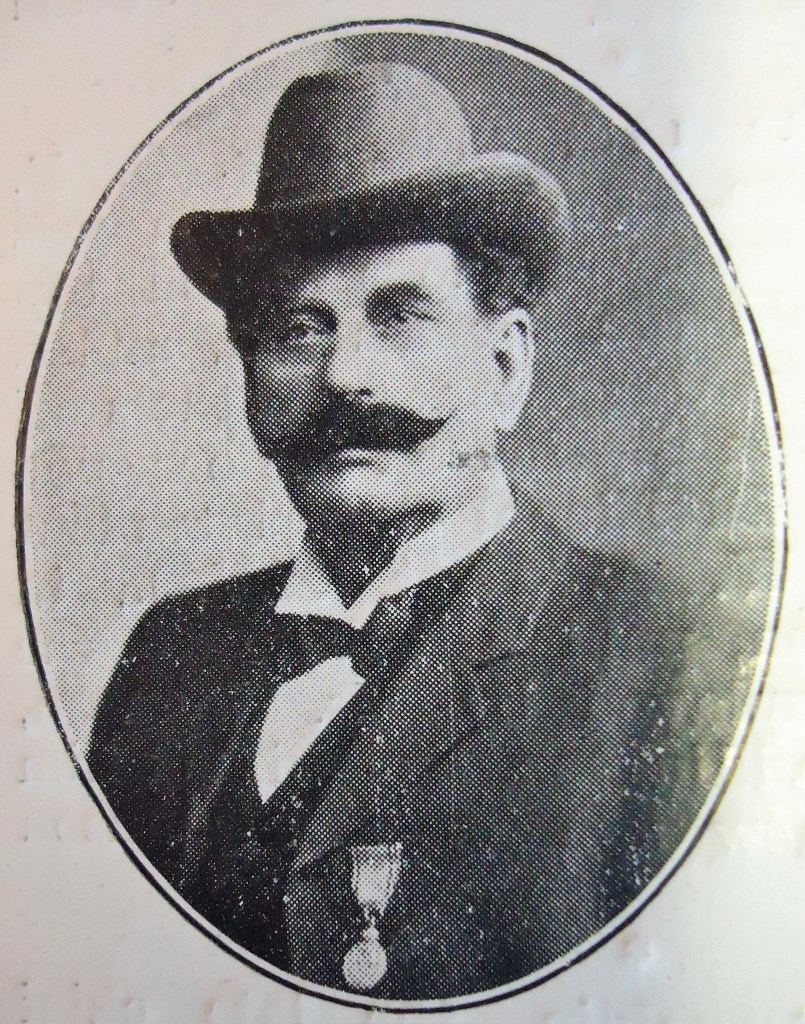

Yesterday I wrote about William Greenaway who received the Royal Victorian Medal, which he is seen wearing in this photograph.

Now read about his role in the record breaking train journey when the Prince and Princess of Wales traveled on ‘The City of Bath’ loco.

The Royal Visit

Prince and Princess of Wales in the West

A Record Run

His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales accompanied by his Royal Consort, arrived at Paddington yesterday morning to entrain for Cornwall, in order to attend the ceremony of dedicating the new Nave of Truro Cathedral. Their Royal Highnesses were attended by Lady Lygon, Sir Arthur Bigge, the Hon. Derek Keppel, and Captain Godfrey Faussett. The train with the Royal party left Paddington precisely at 10.40 a.m. Instructions had been given to keep the line clear for a run to Plymouth without a stop – a distance of 246 miles 5 furlongs.

The Royal train was due, according to the arranged table, to pass Exeter at 2.5 p.m., and just before two o’clock several persons proceeded to St David’s Station with the object of catching a glimpse of the Royal Party. Many, however, arrived too late. The train had favourable weather, and made an unexpectedly rapid run, passing the middle signal box at St David’s at 1.33, exactly 32 minutes ahead of her time.

At Exeter.

About a hundred people had assembled on the station. Of course, there was no opportunity for demonstration, as the train passed through at the rate of about twenty miles an hour. Inspector Greenaway was noticed to be on the engine, which is one of the latest turned out from the Swindon works. She is one of the largest types, having 6ft. 8in. three coupled wheels, and is named “The City of Bath.” Around the funnel she bore the Prince of Wales feathers. Behind the engine was a saloon, then a composite carriage. Next came the Royal saloon carriage, followed by a compo and a brake coach.

The journey is a remarkable one, and establishes, we believe, the long distance record not only for the United Kingdom, but for the world. The train started from Paddington at 10.40 a.m. and reached Exeter, a distance of 194 miles, at 1.33 p.m.: that is to say, she covered the distance in 2 hrs. and 53 minutes or at an average speed of 67 miles an hour.

On the whole, the line is good between London and Taunton, there being a falling gradient for almost the whole distance. The tender of the engine carried about five tons of coal, and water was scooped up from the troughs near Goring and also near Bristol.

In the run to Chippenham the train made a gain of 16 minutes, and, despite the rising gradient from Taunton to Wellington, managed to increase this advantage on the arranged time to 32 minutes by the time Exeter was reached. She gained 21 minutes in the run from London to Bristol, and 15 minutes from Bristol to Exeter.

This, of course, constitutes a record run from London to Exeter, the previous best performance being by the London and South Western’s 11 o’clock express from Waterloo which does the journey in 3¼ hours, beating the Great Western’s first “Cornishman,” which has been put on occasionally to meet heavy traffic, and which is to run permanently from the 18th of this month, by fifteen minutes. The L. and S.W. route is, it must be remembered, shorter by about 25 miles.

The Royal train yesterday knocked off 37 minutes from the “Cornishman’s” time, and beat the L. and S. Western’s fastest express by 22 minutes. She overtook the 9 a.m. express, which, however, arrived at S David’s at 1.54, only four minutes late.

From Exeter to Newton.

Continuing her journey, the Royal train reached Newton Abbot from Exeter in 22 minutes, despite the fact that twice she had to slow down to take up the staff. From Newton Abbot to Plymouth the road becomes rough. The gradients are numerous and stiff, and form a kind of switchback railway. But the train continued to gain time, Plymouth being reached at 2.34. The journey therefore, of 246 miles 5 furlongs was covered in 3 hours and 54 minutes, or an average speed of a fraction over 62 miles an hour. When allowance is made for the fact that in climbing steep banks and in passing through big stations, and in taking in staffs, the pace has to be reduced to about 20 miles an hour, it is evident that on some favourable sections of the line a terrific speed must have been registered, somewhere at least from between 70 and 80 miles an hour. It is probable that the latter speed was exceeded between Whiteball tunnel and Exeter.

The Great Western, however, are not, we understand, likely to run a regular train from Paddington to Exeter in 2 hours 53 minutes. They have done the journey on the present occasion to show what is possible, but they are likely to be content with their ordinary time of 3½ hours, which, after all is fast enough for the majority of people. It is true that they are 15 minutes slower than the London and South Western to Exeter, but they beat the latter on the longer journey from London to Plymouth (North-road) by just two minutes.

Following is the time table, scheduled and actual of the journey:-

Schedule Actual

Paddington 10.40 10.40

Bristol 12.04 12.25

Taunton 12.35½ 1.03

Exeter 1.01 1.33

Newton 1.21 1.56

Plymouth 3.10 2.34

Grampound Road 4.30 3.50

The distances are:- London to Bristol 118½ miles, London to Taunton 162¾ miles, London to Exeter 193½ miles, London to Plymouth 246 miles.

It is said that the fastest bit of running during the journey was down the incline from the Wellington bank to Exeter, where, it is estimated, that a rate of 85 miles an hour was attained.

At North Road

When the train drew up at North road the public attendance was small. The Earl of Mount-Edgcumbe was present accompanied by Mr H. Adye, the Superintendent of the Plymouth division of the GWR. As soon as the train came to a standstill the noble Earl entered the Royal saloon, and was received by the Prince, who presented him to the Princess. Their Royal Highnesses did not leave the carriage. The Princess was attired in a violet coloured dress. Dr. Ryle, Bishop of Winchester, joined the train at Plymouth.

During the stop at Plymouth Mr T.J. Allen, the superintendent of the line, who was in charge, entered the Royal saloon, and was assured that the journey had been covered without discomfort to their Royal Highnesses.

After the engine had been changed, the train left at 2.46 for Grampound-road. Among those on board were Mr Waister, of the locomotive department, Swindon; Mr J.V. Williams, of the timetable department; Mr W. Simpson, of the advertisement department, and Colonel the Hon. Edgcumbe, one of the Directors of the Company.

The nearest approach on the Great Western Railway to yesterday’s performance was on the occasion of the visit of HM the King to the West, when the special train took his Majesty from Millbay to London in four hours and twenty minutes.

The Prince and Princess of Wales arrived at Grampound-road Station, Cornwall, very much in advance of the scheduled time…

The Western Times Wednesday July 15th 1903

A Unique Distinction

The brief official announcement yesterday that the King had presented the Victorian medal to Locomotive Inspector Greenaway, of the Great Western Railway, has created the liveliest interest in railway circles. So far as memory serves the distinction is unique; and if it be so, the Great Western Railway Company and all the employes on that great system have reason to plume themselves on a very gratifying event. The bestowal of knighthoods and other honours on the leading railway managers in this country is not unusual; and individual employes have received marks of Royal favour. But the conferment of the symbol of a special order on a member of the mechanical staff is a departure worthy of more than passing note.

As the railway that links the Metropolis to Windsor, one of the favourite palaces of the late Queen Victoria, the Great Western has, of course, played an unusually prominent part. The medal of which Inspector William Greenaway has been the enviable recipient is designed to recognise the services of that painstaking official. The inspector was in charge of the engine that drew her late Majesty’s Diamond Jubilee train in 1897, and he has travelled with the Royal train on every subsequent occasion, including the removal of Queen Victoria’s remains from London to Windsor. From this it is to be inferred that when Queen Victoria made her long journeys from Windsor to Balmoral the engine of the Royal train was under the sole charge of Inspector Greenaway.

Only those who know something of the elaborate nature of the preparations for the passage of a Royal train, even over a comparatively short length of railway, can realise the amount of responsibility that devolves on the officials concerned. The passage of a Royal train entails the drastic revision of time-tables, the general regulation of traffic within certain hours at certain points, the posting of extensive cordons of platelayers, the issue of special instructions to signalmen, and a thousand and one things that would never even occur to the non-technical mind.

In conferring the Victorian medal on Inspector Greenaway, King Edward has inferentially recognised all this. His Majesty, whilst honouring the individual, has honoured also the class to which he belongs. To the King and the members of the Royal Family, the railways are as essential as they are to the humblest passenger. The special Royal train is, of course, an institution by itself, but the men who take charge of it, either on its long or short journeys, are not trained specially for the purpose. They gain their experience in the service of the general public, just as the soldier who wins a commission gains his knowledge by real warfare in the ranks. It is from the common school of experience that the best men make their way, and there is something distinctly agreeable in the idea that King Edward, in the midst of the urgent pre-occupations of the Coronation year, should have bethought him of the claims of a representative of a service which is nowadays too often regarded as one of the merest commonplaces, though it is well to recollect that when Queen Victoria ascended the throne the railways of Great Britain and of the world had scarcely emerged from their rudimentary stage. Yet we find them, at the commencement of the Edwardian era, a mighty, irresistible, and indispensable force – a force that has been repeatedly recognised by the Sovereign, but never, so far as we are aware, in precisely the same way as King Edward has been graciously pleased to recognise the services of Inspector Greenaway…

Extracts from the Western Daily Press, Bristol, Tuesday, May 13, 1902.

You may also like to read:

William Greenaway MVO