The re-imagined story …

There are two highlights in the Swindon calendar for the children – Trip, when the Works shut down for the annual holiday and we go to the seaside, and the Children’s Fete, and I can never sleep the night before either of them.

Preparations for the Children’s Fete begins well in advance and I have first-hand knowledge of this as my father is on the Mechanics’ Institute Council and our whole family is involved.

The fete takes place in the GWR Park, the gates open at half past one. Tickets cost 3d for adults and 2d for children. The children receive two free rides on the steam roundabouts, a drink of either tea or oatmeal water and a piece of cake.

For weeks beforehand we save every penny, ha’penny and farthing we can; never have so many errands been run, so many jobs done about the home.

The familiar GWR Park becomes kaleidoscopic with rides and stalls and fairy lamps festooned around the Cricket Pavilion and the bandstand. Entertainments on the central stage take place throughout the afternoon; comedy acrobats and trapeze artistes and trick cyclists and one year there was even a troop of performing dogs. Mr Harvie is the chairman of the fete committee and director of amusements but this isn’t what he became best remembered for.

The event runs like a well-oiled machine, which is hardly surprising as it is organised by some of the most well qualified and experienced engineers in the railway works. And perhaps the greatest feat of organisation is the cake.

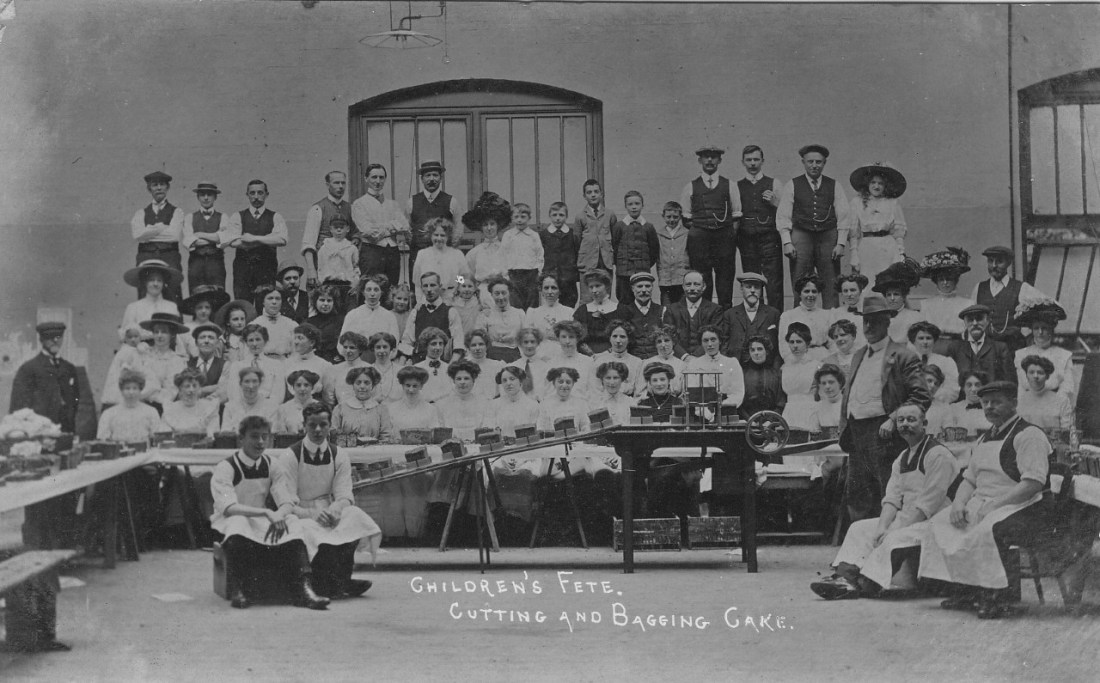

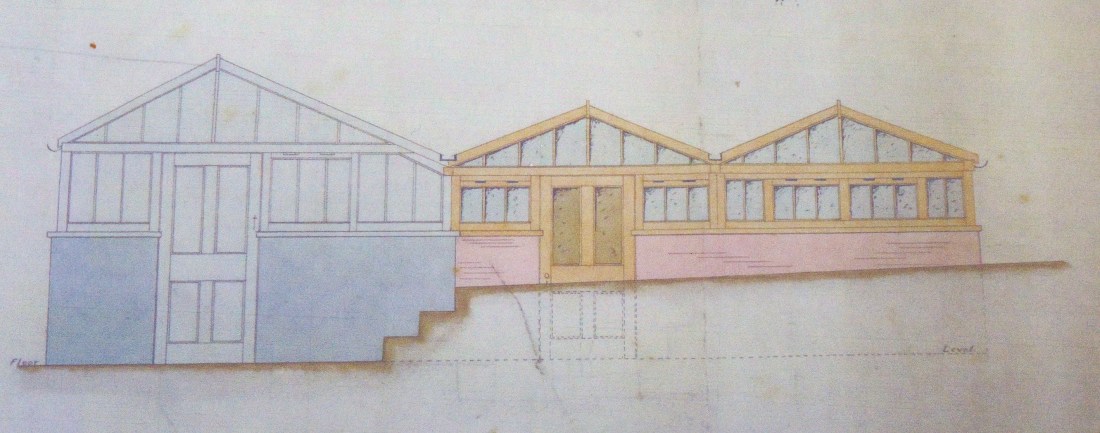

The quantity of cake required was enormous, amounting to no less than 2 tons 13 cwts. The job of baking it went to Mr E.P. Monk of Old Swindon who produces annually approximately 1,200 cakes weighing 5lbs each. Next comes the task of cutting the cakes into half pound slices, a job which had previously fallen to a handful of volunteers. It used to take 12 people approximately six hours to cut up and bag the cake. And then Mr Harvie invented the Multiple Cake Cutting Machine.

At this year’s event Mr Harvie’s new improved machine will be used for the first time. The machine, a dangerous looking contraption, is composed of crossed knives, balanced on spiral springs, which hover above each cake. The average speed of this new machine being no less than 6 cakes, or 60 half pounds per minute. The cakes are fed into the machine on 12 wooden trays by an endless band on rollers worked by the handle at the end of the machine, and here Mr Harvie has introduced another novelty in the shape of an electric bell, which is so adjusted that when the tray reaches the exact centre of the knife it strikes two levers and forms an electric communication with the bell, which commences ringing, and continues to do so until the cake is cut. The tray then passes on with the cake to make room for the next. When the tray on which the cake is cut reaches the end of the machine, it runs on an inclined board which carries it to the packers.

So exciting is the whole process that I think it should form part of the entertainments on the fete stage. Perhaps I’ll suggest that to Mr Harvie for next year.

My fete dress hangs on the back of the bedroom door. My hat, decorated with ribbons and flowers, sits on the dresser. I open the curtains a crack, it is not quite dark yet. Early tomorrow morning my father will join the others assembling the stage. I squeeze my eyes tightly shut. I must go to sleep, I must go to sleep.

The facts …

William Harvie was born in Islington, London in c1849. He began his career as a coach trimmer in Birmingham where he met and married his first wife, Susan Newman, at St Peter and St Paul’s Church, Aston. Susan was a widow with a young son. By 1871 the couple were living at Rushey Platt with Susan’s son Edward and two children of their own, Henry and Louisa. They would have a third child George William. The family lived at 15 Faringdon Street for a number of years and by 1891 William had been promoted to foreman.

He served as foreman over the women in the polishing shop, and during the 1890s he was responsible for organising the entertainment for the ‘annual tea of the female staff employed in the Carriage Department.’ He even performed a couple of humorous songs, said to have contributed to the event.

By the time of Susan’s death in 1906 they were living at 6 Park Lane. Two years later William married again. His second wife was Alice Elizabeth Turner. She died in 1921 at their home 92 Bath Road but does not appear to be buried in Radnor Street Cemetery.

William died in 1930. Details of his estate were published in various newspapers, including the Daily Express.

‘A Black Country working lad who, in his spare time, played in a theatre orchestra, became a railway foreman, and dabbled in stocks and shares during fifty years’ service, has died worth nearly £44,000. The workers of this great railway centre used to dub William Harvie of Bath road, Swindon, “the wealthiest workman in England,” but even they were surprised when his estate was announced, and the sole topic of conversation in the town was the large sum he left. He was 84 when he died last October, a widower, and intestate.’

A notice in the Western Morning News reported that he was instrumental in building the first saloon railway coach for Queen Victoria but there is no mention of his famous invention, the Multiple Cake Cutting Machine.

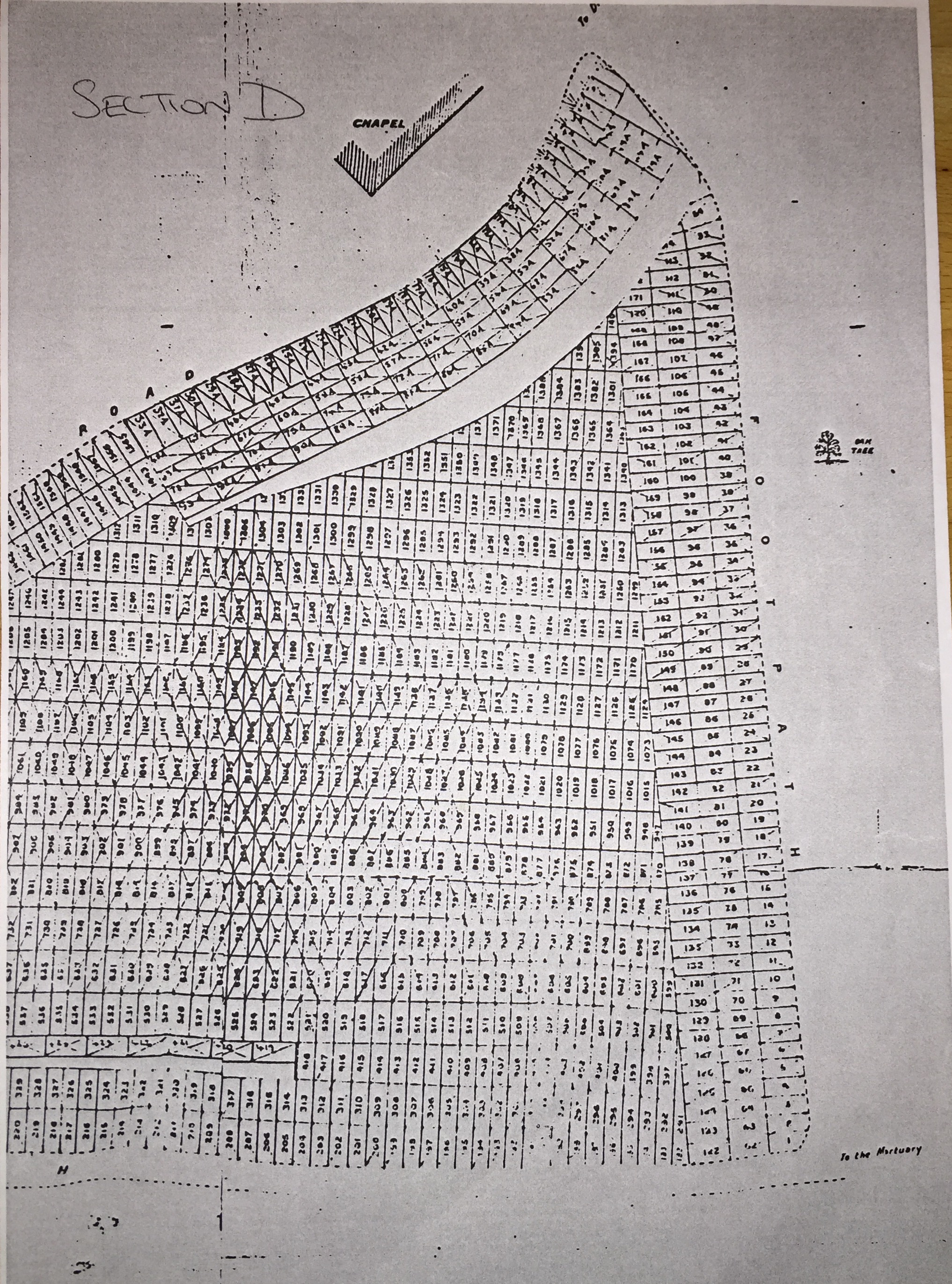

William is buried in plot D14a with his first wife Susan. They were later joined by their elder son Henry.

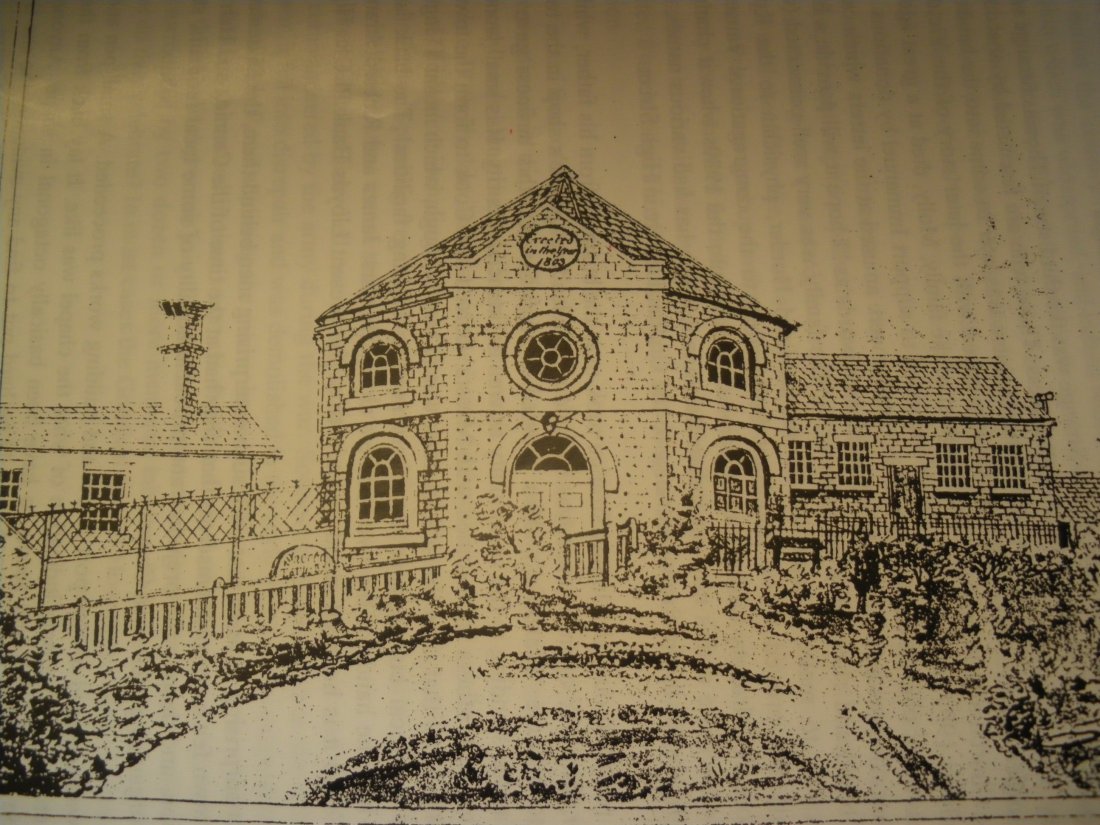

The Strange family were prominent non-conformists in the town and Martha’s father James founded the Congregational Church in Newport Street where members of the family were interred in the small burial ground. The Newport Street Church was demolished in 1866 but the burial ground remained intact for more than 15 years. However, in 1883 the graves of Richard Strange’s immediate family were exhumed for re-burial in Radnor Street Cemetery. The remains of his mother Mary who died in 1829, his father Richard who died in 1832 and his 16-year-old sister Sarah who died in 1820 along with those of Richard’s wife Martha who died in 1858 and a one-day old baby son also called Richard, were re-interred in plots E8463/4/5.

The Strange family were prominent non-conformists in the town and Martha’s father James founded the Congregational Church in Newport Street where members of the family were interred in the small burial ground. The Newport Street Church was demolished in 1866 but the burial ground remained intact for more than 15 years. However, in 1883 the graves of Richard Strange’s immediate family were exhumed for re-burial in Radnor Street Cemetery. The remains of his mother Mary who died in 1829, his father Richard who died in 1832 and his 16-year-old sister Sarah who died in 1820 along with those of Richard’s wife Martha who died in 1858 and a one-day old baby son also called Richard, were re-interred in plots E8463/4/5.