We have long become accustomed to sensationalist tabloid journalism, but the heading in a Victorian issue of the Swindon Advertiser seems particularly insensitive. When a young cricketer collapsed and died on the pitch the heading read ‘His Last Innings.’

George Palmer was born in Northampton in about 1861 and we learn from the inquest report that he had served in the army in India before arriving in Swindon. At the time of the 1891 census he was lodging with William and Lucy Taylor at 20 Percy Street, Rodbourne where he worked as a Blacksmith’s Striker in the Works. He married Charlotte Annie Varney at the parish church in Fairford just seven months before his death.

His Last Innings

Sudden Death in the Cricket Field at New Swindon

A Cricketer Falls Down Dead

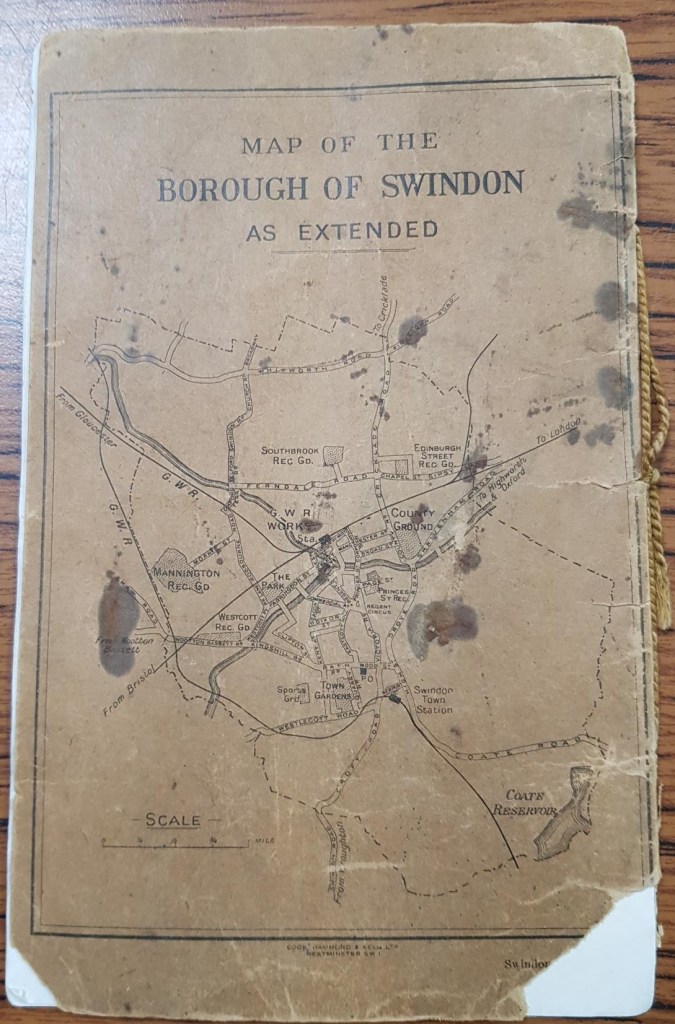

A shocking case of sudden death happened in the Recreation Ground, New Swindon, on Saturday afternoon. A young man named George Palmer aged about 34 years, and living at 15, Percy-street, Even Swindon, was playing for the Even Swindon Cricket Club against another New Swindon team. He was batting and had just hit a ball for five runs. Afterwards he made one run, and had just got to the wicket when he fell down dead. As he fell he uttered the words “Cover up my head,” and never spoke again. A doctor was sent for, who pronounced life extinct. The body was removed to deceased’s home, and Mr Coroner Browne communicated with. Deceased had only been married a few months.

The Inquest

An inquest was held on the body of deceased on Monday afternoon at the Dolphin Inn, Even Swindon, before Mr W.E.N. Browne, County Coroner, and a jury of whom Mr H.G. Hughes was foreman.

The first witness called was Henry Brooks, a GWR employe of 4, East-street, New Swindon, who said he knew deceased well. He had never heard him complain. Witness was umpire in the cricket match in which deceased was playing on Saturday. He was quite cheerful when he commenced playing in the match on Saturday. He had made eight runs, and had run six of them, when he fell down by the wicket. Witness thought deceased was in a fit. He was taken underneath a tree, and as he lay there he said, “put something over my head.” Deceased did not speak again, and died immediately. Witness had heard that deceased received a blow from a cricket ball whilst playing a match a few weeks ago.

Mr Hayward, a juryman, said he heard that deceased said as he was going to the match that he hoped he should not have a fit again.

Wm. Palmer, brother of deceased, said he saw him on Saturday morning, and he was quite well then. Deceased was struck with a ball on the temple about a month ago. On Saturday witness was playing with deceased in the match. He saw deceased fall, and went and fetched some water, but deceased did not speak again.

Dr. Howse, partner with Dr. Swinhoe, said he was called to deceased in the Recreation Ground, and found him quite dead. He had since ascertained that deceased had serves in the Army in India, and had a sunstroke. The circumstance tended to produce a weak heart and the excitement of violent exercise and the heat of the day would cause sudden stoppage of the heart’s action. In his opinion death was due to syncope or sudden failure of the heart’s action.

The jury returned a verdict accordingly.

George was buried not in Radnor Street Cemetery but in the churchyard at St. Mary’s, Rodbourne Cheney on June 19, 1895.

The Funeral

of deceased took place on Wednesday. Mr. Palmer had been a member of the Even Swindon United C.C. since its formation, and was always held in very high esteem by his own clubmates and local cricketers generally. Consequently a very large following from the various clubs in the district attended to pay their last respects, besides a good muster of his old shopmates and friends, numbering altogether upwards of 170. The houses en route to the church at Rodbourne had with few exceptions the blinds drawn and the route was lined with a large concourse of sympathising onlookers. The funeral service was conducted by Rev. C.T. Campbell, who delivered a very touching address at the graveside. The wreaths and flowers sent by various clubs and friends formed quite a floral display. The corpse was borne by eight members of the Even Swindon United C.C.

The Swindon Advertiser, Saturday, June 22, 1895.