How we like to moan about good old ‘health and safety’ regulations. What a nuisance it all is – well this is how life was before we had such protection.

When John Parkinson went to work that Tuesday in October 1901 it was just another day in the railway factory. By eight o’clock that evening he lay dead in the Medical Fund Hospital, his wife Kate a widow and his four young sons Ernest 8, George 6, Percy 4 and 2 year old Wilfred without their father.

The Fatal Accident in the GWR Works

A Rodbourne Man Killed

A terrible accident occurred in the GWR Works, Swindon, on Tuesday, which, unhappily, terminated fatally. A man named J.E. Parkinson, of 46, Linslade-street, Rodbourne, and engaged in the boiler shop of the GWR Works, was the victim, a large boiler falling on his back, and inflicting such injuries that his life was despaired of from the first. The accident happened about four o’clock on Tuesday last, and the unfortunate fellow, who was 31 years of age, was conveyed to the GWR Medical Fund Hospital, where Drs. Rodway and Astley Swinhoe attended to his injuries. The injuries to the back and sides were so terrible that it was utterly impossible to do anything more for the unfortunate man than give him stimulants and keep him warm. He only lingered four hours, passing away soon after eight o’clock in the evening. He leaves a widow, who is prostrated with grief, and four children.

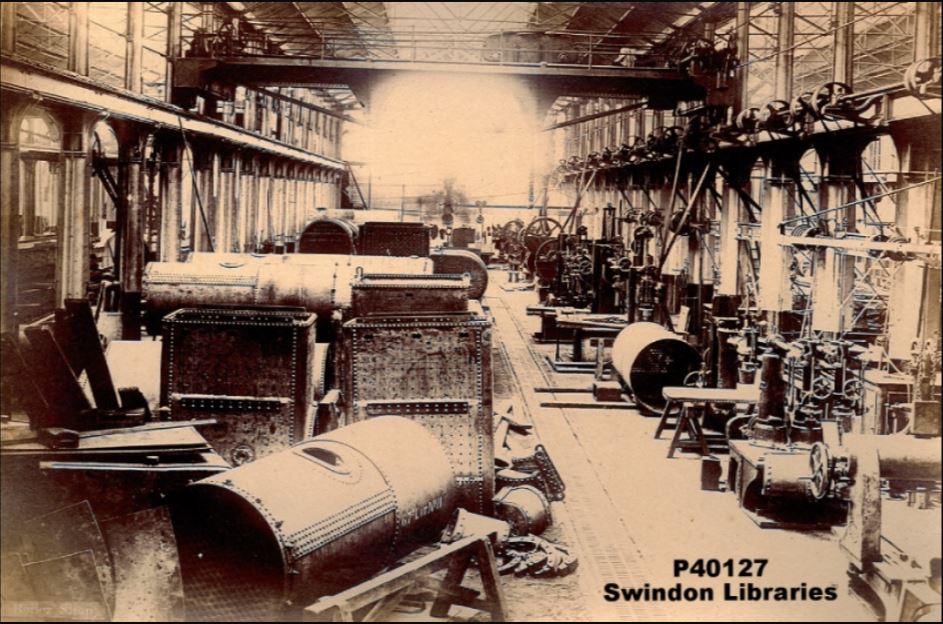

GWR Boiler Shop c1886 – image published courtesy of Local Studies, Swindon Central Library.

The Inquest

Was held yesterday (Thursday) afternoon in the Council Chamber of the Mechanics’ Institution, by Mr Coroner W.E.N. Browne, and a jury, of which Mr. Thos. Tranter was chosen foreman. There were also present J.S. Maitland, Esq., H.M. Inspector of Factories, and Mr. A.E. Withy, representing the widow of deceased.

The Jury having viewed the body, the first witness called was William Simpkins, employed in the GWR Works, who was working on the boiler at the time of the accident. His evidence went to show that the boiler was mounted on trestles outside the shop. It had been there about three weeks. It was an ordinary engine boiler, and the trestles were standing on the bare ground. He did not notice anything wrong until a minute before the accident happened, and then he saw the trestles were sinking at one end. He gave the alarm, and one man was got out from the smoke box end, but the deceased was too late, and the boiler caught him as it tilted over.

By the Coroner: Is it usual to do this kind of work with the boiler mounted on trestles? Sometimes they are mounted on bogies, but they are done as much one way as another. – Has there ever been any accident before? Not to my knowledge.

By the Inspector: since the accident iron plates have been put under the trestles. Is that any improvement? Yes, undoubtedly.

By Mr Withy: Was it impossible for the man to get away after the warning was given? Quite impossible.

At this point a desire was expressed on the part of the jury to see the spot where the accident happened, to which the Coroner agreed.

Upon returning, Charles Bray, who was also working on the same job, gave evidence. He said that when the boiler began to slip, he shouted, and the man in the smoke-box end was got out. He then shouted to the man in the fire-box end, who said “What’s up?” He (witness) said that the boiler would fall presently, as the trestles were giving way. Parkinson then tried to get out, when the boiler went, crushing him between it and the packing.

By the Coroner: How long had the packing been there? I couldn’t quite say. – Were the trestles good? They were when they were put up. – Was there anything under the trestles- plate or anything? No. – Is this usual? Yes. – Was the boiler empty at the time? No, full of water, and deceased was marking what tubes had to come out.

Mr Llewellyn Dyer, foreman of the B Shop, was the next witness. In answer to the Coroner, he said that the trestles were quite strong enough. – Is it usual to put boilers on trestles? Yes, it is done every day. When they had sufficient bogies they were used, and when not they were put on the ground. – Had deceased stopped in the boiler, would he had been safer? Yes, I think so.

By the Inspector: Whose duty was it to see the boiler put on the trestles? My own nominally, but necessarily I have to leave details to others. – Will precautions be taken to prevent similar accidents in the future? You my take it from me, sir, such an accident will never occur again. – Witness went on to state that the ground on which the boiler stood was new ground, and had not, previous to a month ago, been used for the purpose for the past 30 years.

Dr. G. Rodway Swinhoe gave evidence that he attended the deceased soon after the accident, and found him suffering from very severe shock. After examination he was put to bed, and stimulants were administered, but he was too bad to be moved about. Deceased never recovered from the shock, and this was undoubtedly the actual cause of death.

The Jury returned a verdict of “Accidental Death,” caused by severe shock to the system, through the accident.

At the conclusion of the enquiry, Mr. Dyer stated that a communication would be sent to Mr. Maitland by the Manager of the Works stating what steps had been taken to prevent a recurrence of the unfortunate affair, at which the Inspector and Coroner expressed their satisfaction.

Swindon Advertiser, Friday, October, 18, 1901

The Fatal Accident in the GWR Works

Funeral of the Deceased

The body of John Ernest Parkinson, of Linslade Street, Rodbourne, who succumbed to injuries received in the GWR Works, Swindon, on Tuesday week, as already reported in our columns, was interred in the Swindon cemetery last Saturday morning. Nearly a hundred persons followed the coffin to the grave, the chief mourners being the deceased’s widow, his mother, and children. Mr. C. Hall and Mr F. Green, assistant foremen in the same shop that deceased worked in, followed many shop mates and others being present. The Rev. F.J. Murrell (Wesleyan) conducted the service, and the coffin, which was of elm with black fittings, was covered with floral tributes….

Mr Charles Dunn carried out the funeral arrangements.

Extracts from the Swindon Advertiser Friday October 25, 1901.

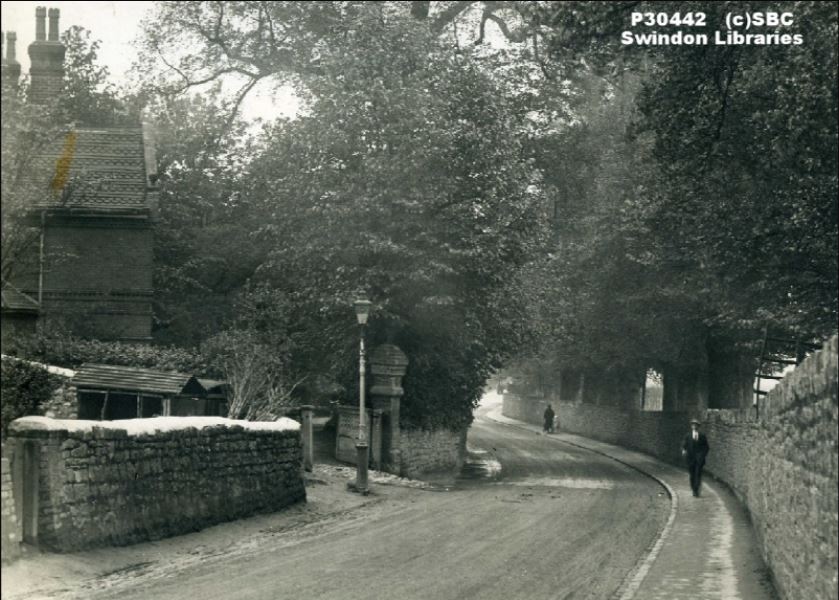

Linslade Street, Rodbourne c1920s image published courtesy of Local Studies, Swindon Central Library.

When John Ernest Parkinson married Maud Mary Kate Clack at St. Mark’s Church, Swindon in 1892 he gave his occupation as Cheese Monger and an address in London. By the time of the census in 1901 he describes his occupation as a Locomotive Boiler Tuber in the GWR Works here in Swindon.

His funeral took place on October 19, 1901 and he was buried in grave plot C1979 where he lay alone for 74 years. In 1975 his son George Clement Parkinson was buried in the same plot and two years after that Kate Parkinson (most probably George’s wife) joined them.