The re-imagined story …

The houses in Medgbury Road looked exactly like ours in Derby. I don’t know why I was surprised. We were exchanging a home in a northern railway town for one in Wiltshire, of course there would be similarities. I just didn’t take account of how many there would be though.

The old canal ran alongside Medgbury Road, silted up and no longer in use, while row upon row of red brick terrace houses stretched back to the railway line.

We were moving to Swindon to make a new start. I don’t know how we thought that would be possible. To begin with we had a kind of excitement, but I soon realised we lacked imagination. Perhaps it was the grief. We were no different to anyone else; how could we have ever thought it would be otherwise?

Every household, every family had someone employed in the railway works and in 1920 everyone had been touched by four long years of war.

When my new neighbour told me about the Chiseldon Camp accident it felt as if it had happened just yesterday, so intense was her grief.

“We knew them all. You did in a street like this. Watched them grow up, start school, start work,” she said. “It was the Easter weekend, the year after the war ended. The boys were off to Liddington Castle for the day. They took a few sandwiches and some pop. It was all so innocent. Just a day out in the country. A few games with their friends.

“One of the boys suggested walking over to the practise trenches at the Chiseldon Camp. They split into two groups and just seven of the boys chose to go on to the Military Camp.

“Albert Townsend watched his mate Fred pick up something that looked like a rolling pin, and roll it down a bank,” she pulled a handkerchief from her apron pocket. “Three of the boys were killed outright, only one of the seven escaped injury.”

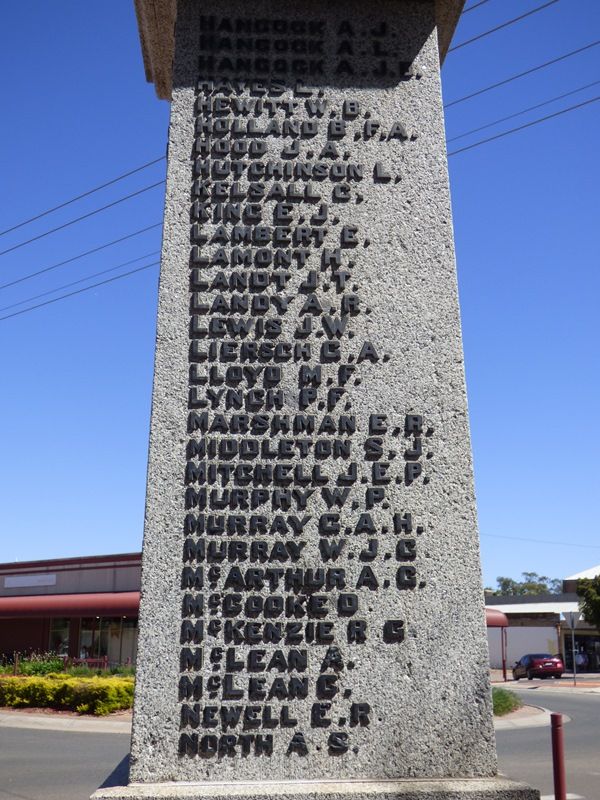

There was talk of setting up a memorial in the cemetery, she told me, raising a public subscription, but people just didn’t have the money in those first years after the war. There were already a growing number of memorials appearing across the town commemorating too many dead. But the boys’ story would long be remembered and the mothers of Medgbury Road would never forget.

We lived in Medgbury Road for a year and then we moved back to Derby. How did we ever think we could forget? Why would we want to?

The facts …

The funeral of Frederick Cosway 14, Frederick Rawlinson also 14 and 13-year-old Stanley Palmer, the adopted son of Elizabeth and Henry Holt, took place on April 24 1919 and was attended by what was described as ‘an immense throng’ of people.

The funeral procession started from the boys’ homes along a route lined with spectators and proceeded to the Central Mission Hall in Clarence Street. The congregation numbered approximately 800 with many more standing outside the hall.

The report of the funeral continued:

“Two of the coffins were conveyed in shillibiers and the third on a handbier. There was a great profusion of flowers. The chief mourners followed in carriages. They included the parents and other relatives of the deceased lads. Between 30 and 40 lads, companions of the deceased, followed on foot.

As the procession wended its way to the Cemetery rain commenced falling heavily, but it proved to be a storm of short duration. The interment took place in the Cemetery in the presence of several thousand spectators, and the service, which was conducted by Pastor Spargo, will long be remembered by all who took part.”

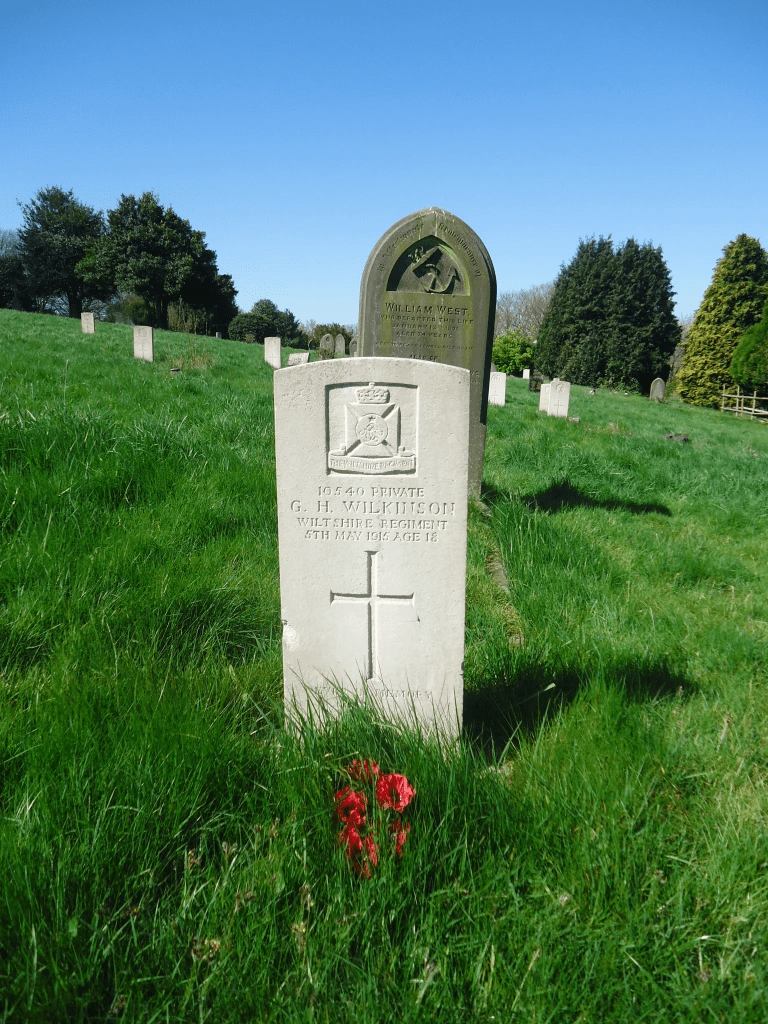

The three boys were buried together in plot C728. Today there is no memorial to mark the spot.