The re-imagined story …

They are bringing him home tomorrow.

The grand entrance hall at The Croft is made ready with vases of white roses and arum lilies on every polished surface. The sweet scent of jasmine drifts in through the open window. His coffin will stand here until the funeral on Saturday. Friends and family are expected to call and pay their last respects.

I would like to keep a vigil throughout the night. I don’t want him to lie here alone. I would like to sit next to him, rest my hand upon the coffin, speak to him. But this would not be allowed.

I would like to bear the weight of him on my shoulders as his body is borne to the graveside. I would throw myself into the open grave and lie with him through eternity. No one knows the depth of my love for him. No one knows my sorrow, there are others who have more right to mourn than I, my loss is of little consequence.

We had no future, we had no past. I loved him in silence and in secret. There is no one I can confide in, no one I can tell how much I loved him, how much I miss him, how it will always be so.

They are bringing him home tomorrow.

The facts …

George Stanley Morse was born in Stratton St Margaret in 1880, the third child and second son of Levi Lapper Morse and his wife Winifred. In 1891 the growing Morse family lived at Granville House, Bath Road but by 1901 they had moved to The Croft, a property set in more than four acres of land with a paddock, fountain and a tennis lawn. The grounds also contained flowerbeds and terraces with ornamental trees. The magnificent house was approached by a lengthy carriage way and opened on to a spacious, domed hall.

In 1906 George Stanley Morse MRCS LRCP was house surgeon at the Metropolitan Hospital.

Inquest

A Fatal Scratch – Young Surgeon’s Sad Fate

Dr Wynn Westcott held an inquiry this week at Hackney respecting the death of George Stanley Morse, aged twenty-six, house surgeon at the Metropolitan Hospital.

Mr Levi Morse of The Croft, Swindon, MP for the Southern Division of Wilts identified the body as that of his son. He was a healthy young man, and had been at the Metropolitan Hospital about nine months. Witness heard that he had poisoned his finger while making a post mortem examination, and while he lay ill in the hospital he told witness that the affair was purely accidental.

Dr Harry Overy, pathologist at the Metropolitan Hospital, deposed that the deceased gentleman assisted at a post mortem examination on the body of a child who had died from meningitis following ear disease. He had the misfortune to prick one of his fingers, and subsequently he had a fit of shivering, and became ill. Witness saw him on the following day, and found him with a high temperature, shivering, and with some tenderness of the finger. The glands of the shoulder were also tender.

Beyond Help

He was also seen by Dr Langdon Brown and Mr Gask, a consulting surgeon, and some small operation was performed on the finger. ‘In spite of all that could be done, the temperature kept up almost to the end. Death was due to septicaemia, resulting from the prick of the finger.’

The coroner remarked that Dr Morse was held in great respect as a rising young practitioner. The case showed the dangers to which the doctors were exposed.

A Juror: Would it not be reasonable to anticipate awkward results from pricking the finger, and to take steps to render it harmless if possible?

Dr Overy: Mr Morse washed his finger and took the ordinary precautions, immediately after the accident.

The jury returned a verdict of accidental death and expressed their sympathy with the father.

Herald Saturday June 16, 1906.

Funeral of Dr Stanley Morse

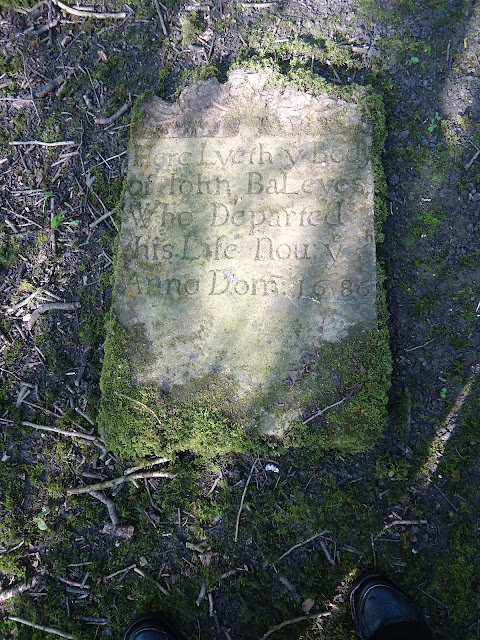

The funeral of Dr Stanley Morse, second son of Mr L.L. Morse MP for South Wiltshire, whose death under sad circumstances was reported in our last issue, took place at Swindon Cemetery on Saturday afternoon. The coffin containing the remains of the deceased was conveyed by train to Swindon on the previous Thursday and rested at The Croft until the time of the funeral. The coffin, which was of panelled oak with massive silver-plated furniture, bore the inscription:-

George Stanley Morse MRCS LRCP Died 12th June, 1906 Aged 26 years

At the foot of the coffin were engraved the words “At Rest.” The first part of the service was held at the Regent Street Primitive Methodist Church, the service being conducted by the Rev W.J.T. Scruby assisted by the Rev George Hunter. After the opening passages of the burial service had been read the hymn “Rock of Ages” was sung, and then the Rev George Hunter read the 90th Psalm. The second hymn was “Oh God, our help in ages past,” and the first part of the service closed with prayer. The congregation stood as the assistant organist, Mr Arthur Barrett, played the “Dead March” in Saul. The concluding portion of the service at the graveside was conducted by the Rev W.J.T. Scruby, in the presence of a very large number of mourners.

A large number of beautiful wreaths and crosses were sent, including tributes from the Residents of the Metropolitan Hospital and Mr Harry Overy; the Medical and Surgical Staff of the Metropolitan Hospital; the Nurses; the Committee, Metropolitan Hospital; the Matron and the Sisters, Metropolitan Hospital; and the Junior Staff and Students of St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

Extracts from The Salisbury and Winchester Journal and General Advertiser published Saturday, June 23, 1906.

George Stanley Morse is buried alone in a double plot E8181/2 in Radnor Street Cemetery. A note in the burial register states “one grave in 2 spaces.” The memorial is a broken column, symbolic of a life cut short.

You might also like to read

Mr Levi Lapper Morse – the end of an era

Winifred Morse – founder of the Women’s Missionary Federation

Regent Street Primitive Methodist Chapel