I’ve had this broken headstone on my to-do list for a very long time. I thought it might prove something of a challenge. I had long wondered who Frederick Millman’s lost wife was and once I discovered her, she pieced together a large Radnor Street Cemetery family history.

Delia Spry was born on December 25, 1805 in Ninfield, Sussex and was baptised in the parish church there on March 26, 1806. In 1829 she married Richard Veness at the Church of St Peter the Great, Chichester.

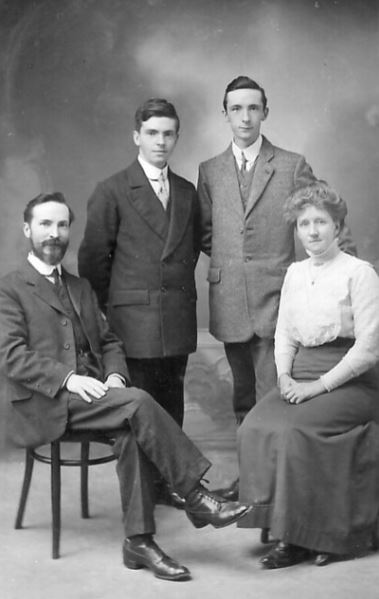

Delia Millman formerly Veness born Spry

I discovered Delia on the 1841 census returns, the first complete census available online. She is living in Hartlebury, Worcestershire, a widow with 5 young children – Maria 10, Jane 9, Thomas 7, Alfred 5 and 3 year old Louisa.

Needs must and it would not be long before she married again. Her second husband was Edward Millman, a bricklayer, and in 1851 the family were living in Wolverhampton. Delia’s two sons by her first marriage have taken their stepfather’s name and Delia has three children by her second marriage – Edward 6, Elizabeth 4 and 2 year old Mary.

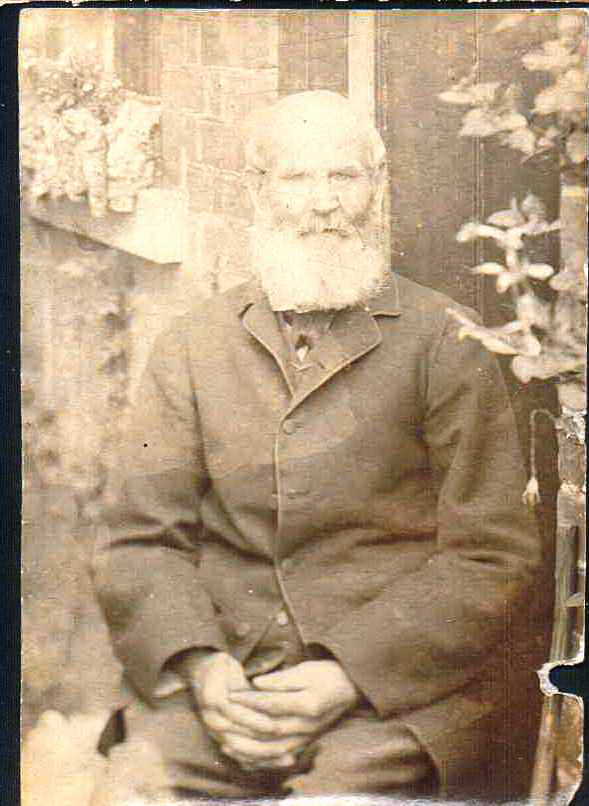

Thomas Veness

By 1881 Thomas Veness, married with four children – Thomas, Alfred, Harriet and Reginald, had arrived in Swindon and the family were living at 30 Sheppard Street. You can read their story (especially that of their daughter political activist Harriet) here.

The death occurred at Worcester, on May 21st, of Mr. Thos. Veness, a retired foreman from the Locomotive Department at Swindon, at the ripe age of 87. Mr. Veness was one of the founders of the Swindon branch of the GWR Temperance Union, and as a member and chairman of the branch Committee rendered great service in the early days of the Union. He was an abstainer for over 60 years and an earnest worker. He was for many years connected with the Band of Hope movement, the Church of England Temperance Society, and the Good Templars. After the formation of a branch of the GWR Union in Swindon he gave himself whole-heartedly to forwarding the work and influence amongst the railway staff.

Great Western Railway Magazine August 1920

By 1881 Delia and Edward had returned to Bexhill but they would soon make there way to Swindon. Delia died at her home, 72 Bridge Street and was buried on January 6, 1887 in grave plot E8430 – the headstone broken and her name missing. Edward died 14 years later, at his daughter Mary’s home, 83 Victoria Road. He was buried with Delia on January 30, 1901.

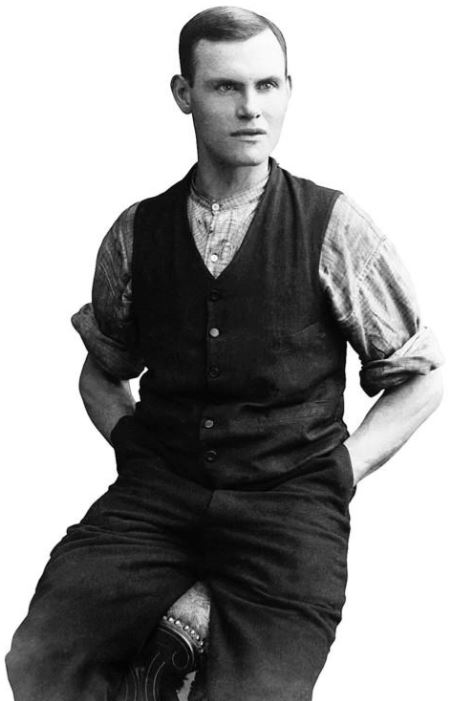

Edward Millman

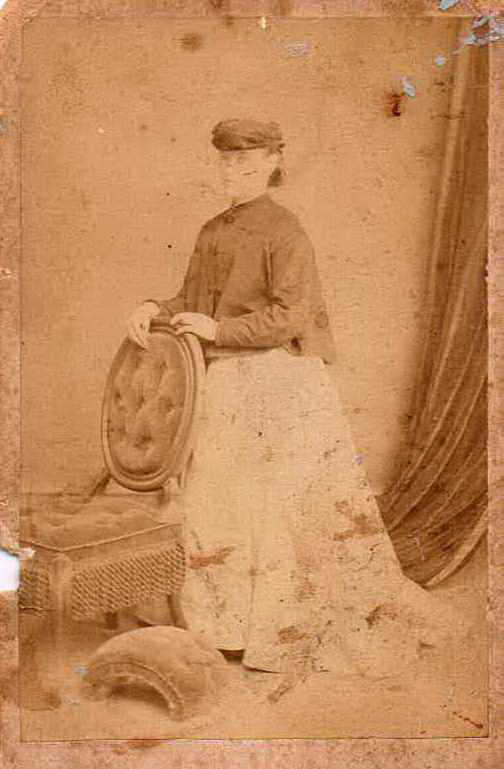

Elizabeth Millman had also made her way to Swindon by 1881. She had married Frederick Benjamin Hook, another bricklayer, and in the census of that year was living in Upper Stratton with Frederick and her family of six children. You can read the sad story of Ben Lawson Hook who died in an accident in the Works here.

Elizabeth Hook nee Millman

Elizabeth died in 1892 and is buried in grave plot B1711 with her husband and her 16 year old daughter Nora who died in 1909.

And finally, (or is there more to discover) there is Mary Millman, Delia’s youngest daughter born in 1848. After working in domestic service as a nurse she married builder Henry William Bennett and by the mid-1870s they were also living in Swindon. (It was at Mary’s home that her father Edward died in 1901).

Mary Bennett nee Millman

Mary died in 1922 and is buried in grave plot C3672 with her husband Henry William, her son Aleck and daughter-in-law Sarah Annie.

My thanks go to family historians Ellen Magill and S.C. Hatt who have generously shared so much of their family history and photographs on Ancestry and Local Studies, Swindon Central Library enabling me to tell all these Swindon stories.