A spur of the moment decision saw me and my two ‘grave’ friends Jo and Tania set off for a trip to the village of Imber. Deep in the heart of the Salisbury Plain MOD training area the village of Imber is inaccessible except on a few, rare occasions during the year and in 2022 volunteers were able to open the church of St. Giles during the late Queen’s Platinum Jubilee weekend.

In 1943 the village was occupied by the War Department for training purposes ahead of the D-Day landings. Already owned by the MOD, the village had long been under siege with villagers well used to a military presence all around them. But when the official order came to give up their homes, the patriotic Imber villagers complied with a heavy heart under the assurance that it would be for the duration of the war alone.

However, when the villagers prepared to return, they quickly discovered this was not, and never would be, possible.

For the story of the campaign to reclaim the village visit the Imber Village Facebook page and watch the video.

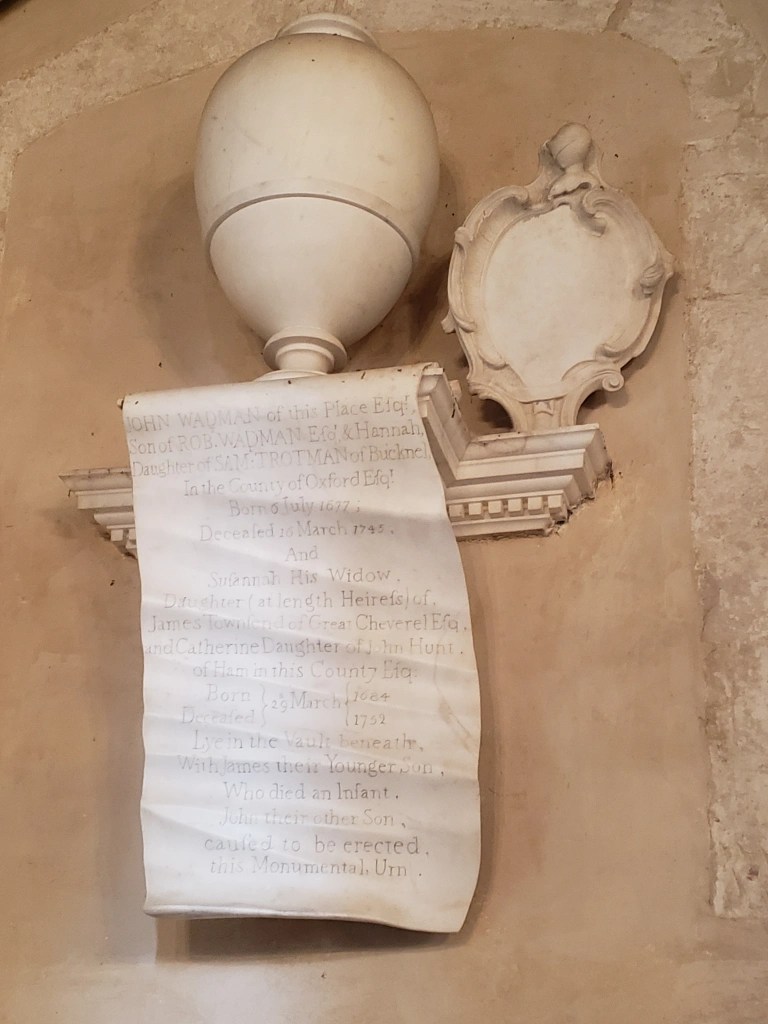

This stylish plaque inside the church is to the Wadman family of Imber Court, Lords of the Manor during the 17th and 18th centuries.

The text of Susannah’s last Will and Testament appears to have been a few informal words, which later required endorsement by two independent witnesses familiar with Mrs Wadman’s writing and signature.

My Son

I desire you will give to the poor of Road, five pounds and to the poor of Imber five pounds, and to the poor of Amesbury ten pounds each to be paid and distributed in a Nook after my Funeral. S:Wadman

My Son

I likewise give ye Servant ye is living with me at my death one years wages and as much of my Wearing Apparel of every kind as my daughter will not accept of

If Mrs Tayler will accept of such part of my Apparel as my daughter shall think proper to part with

(indorsed) This to my Dear Son

Visit the website for the opening dates in 2025 and do allow plenty of time – it maybe awhile before you can make a return visit.