The re-imagined story …

‘Some say it was a futile war, a pointless war, an unjustifiable war. Tell that to Kate Crocker, that’s what I say.

When the old Queen married off her children into European Royal households she did it to create one big family. Well, we all know what families are like – there are favourite children and jealous cousins and an interferring aunt and uncle – but it’s something quite different when family members fall out on the world wide stage. Some people don’t know when they’re well off.

The First World War began when Gavrilo Princip assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, but of course there was more to it then that. The causes of that Great War were many. Tell that to Kate Crocker.

By the time Kate took possession of her son’s war medals she was alone in this world, her immediate family gone, her husband and both her children dead. Europe was a different place as well. The old Queen’s plans for her family had come to nothing. Just like Kate’s.’

The inscription on the headstone reads:

Also George Augustus

only son of G.A. & K. Crocker

Died of wounds received on Active Service

March 15th 1918 Aged 29 years

Interred in St Seves Cemetery Rouen

The facts …

George Augustus Crocker and his sister Edith were baptised together at St. Mark’s on December 3, 1888. The family home at that time was at 28 Reading Street. In 1901 the family are recorded as living at 63 Exmouth Street.

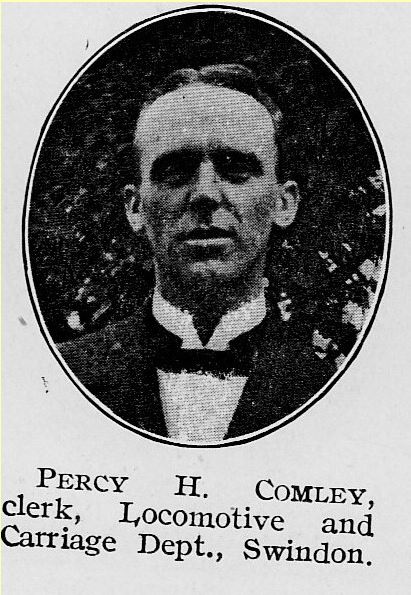

George followed his father into the Works and a job as a railway clerk in the Operating, Traffic, Coaching Depts. He began his employment as a 16 year old on an annual salary of £25 on May 16, 1904.

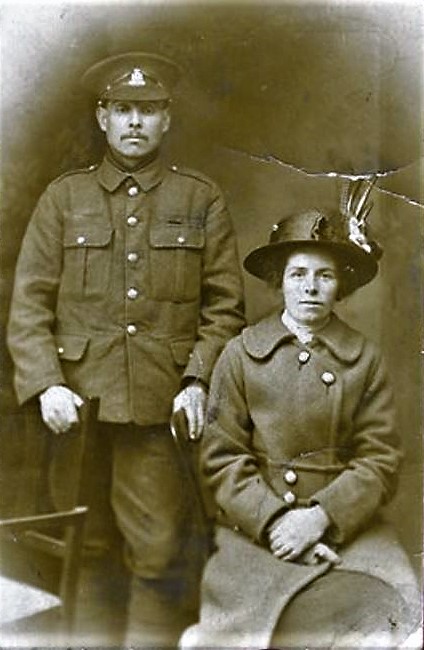

George Augustus Crocker enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps at Swindon on May 10, 1915. He later transferred to 6th Cyclists Bttn Field Ambulance. He died on March 15, 1918 from wounds received in action (Gas) in No 9 General Hospital Rouen. He was 29 years of age. He had served a total of two years and 310 days – a year and 280 days at Home and 1 year and 30 days in France. He is buried in St. Sever Cemetery extension, France. The inscription on his headstone reads – They died that we might live with Mother’s fond love.

He left effects valued at £125 to his mother. Property returned to Kate included letters, photographs and a diary.

Kate Crocker died on June 8, 1938, She is buried in plot E8506 with her daughter Edith who died in 1908 aged 21 years and her husband George Augustus senior who died in 1921. Their son George Augustus is mentioned on their memorial. Ada Emily Jane Crocker, the widow of Rowland Augustus Crocker, George Augustus senior’s brother, was buried in the same plot in 1967.

In the neighbouring grave plot E8507 lies William Crocker, George Augustus senior’s brother, his wife Martha and the aforementioned brother, Rowland Augustus Crocker.

St Sever Cemetery and St. Sever Cemetery Extension are located within a large communal cemetery situated on the eastern edge of the southern Rouen suburbs of Le Grand Quevilly and Le Petit Quevilly. – see www.cwgc.org.