The re-imagined story …

There are two surviving photographs taken that day and in each of them our Elsie looks so sad. You shouldn’t look sad in your wedding photographs – I keep thinking. People say it’s the happiest day of your life. And she looked so beautiful as well.

It was a proper family wedding. All the aunts and uncles were there and three little babies. My was little Joyce noisy, and would she keep her bonnet on? Granny’s dog was better behaved!

Six men in uniform were there that day, including the two grooms. Bert came home, but Elsie lost him anyway. Perhaps she already knew that then, on the happiest day of her life.

The facts …

Herbert Frederick Marfleet, the son of Benjamin James Marfleet a sergeant in the 2nd Dragoon Guards, was born in the Punjab in 1891. By 1901 the family had returned to England and Benjamin was working as a Railway Shop clerk in the GWR Works. On leaving school Herbert followed his father into the railway factory as an apprentice coach finisher.

In 1915 Herbert joined the Royal Army Service Corps serving first in Egypt. In 1917 he briefly returned home to Swindon to marry his sweetheart Elsie Morse. Elsie was the eldest of William and Agnes Morse’s seven children. By 1911 Elsie’s father had died and Elsie, aged 18, was working as a finisher in a clothing factory. This could have been either Cellular Clothing in Rodbourne or John Compton’s in Sheppard Street. The family lived at 4 Albion Street where these wedding photographs were taken in the back garden in 1918 when Elsie and her sister Agnes married in a double wedding. Agnes’ bridegroom was a Canadian by the name of Hooper Gates. Hooper survived the war.

Immediately after the wedding Herbert returned to his regiment in Salonika where he contracted malaria. He was discharged from the army and returned to Swindon in the spring of 1919 but died just a few weeks later.

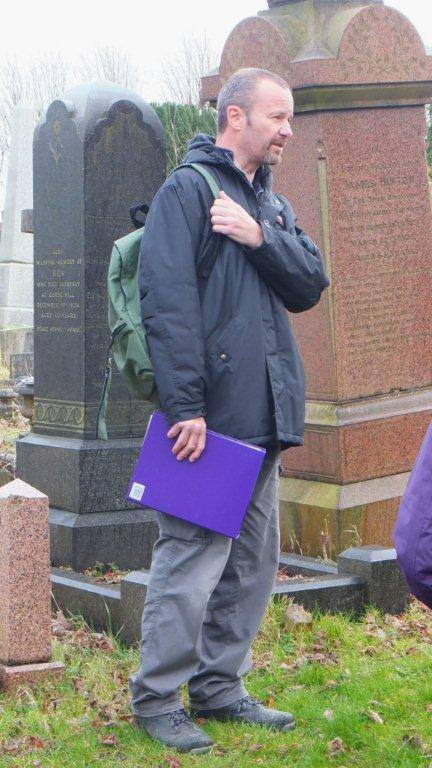

It was at first thought that he lie in an unmarked grave in the cemetery but it was later discovered that he was buried with his aunt and uncle, Matilda Hammett and Edward Johnson. He was, however, entitled to a Commonwealth War Graves official headstone as his death was a direct cause of his military service. The official application process began in May 2011 and the headstone was erected in June 2015. Guest of honour at the dedication ceremony was 98 year old Joyce Murgatroyd, his only known living relative, who as a baby is pictured in the wedding photograph.

First published on April 20, 2022.