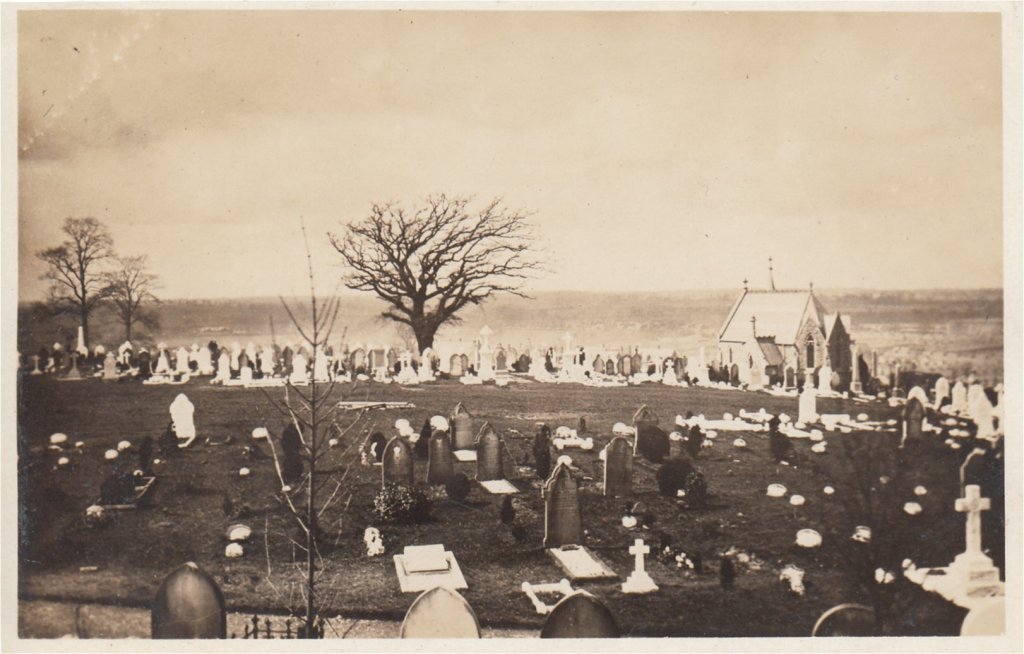

Image of Drove Road taken c1926 and published courtesy of Local Studies, Swindon Central Library.

Emma Louisa Newberry died in 1964 aged 96 years. Emma was born in Guernsey in 1867. She had lived through almost a century of enormous social change including two world wars, the second of which saw the German occupation of her former island home.

Unfortunately, I can find out very little about her family background, not even her maiden name, but I will continue to research.

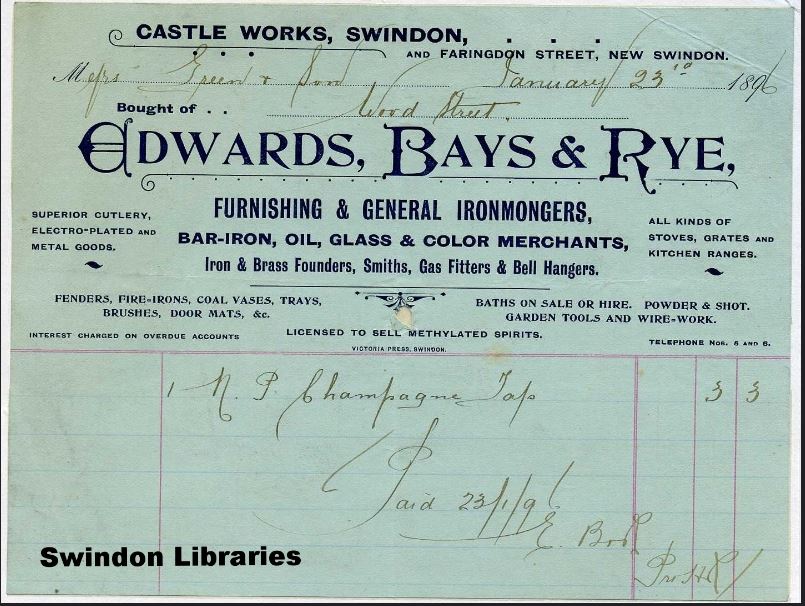

By 1893 she had married Ernest Walter Newberry, a gas fitter, quite probably in Guernsey where he was also born and raised. Emma’s Swindon story begins in 1894 when her daughter Gertrude May was baptised at St. Mark’s Church on May 27. Emma and Ernest, who was employed in the GWR Works, then lived at 28 George Street. In 1901 they were living at 54 Dean Street where their second daughter Clarice Louise was born. In 1939 Ernest and Emma were living at 86 Drove Road, their last home together.

Emma outlived not only her husband Ernest but both her two daughters as well. She died in the Isolation Hospital, Swindon on May 17, 1964.

Emma was buried on May 22, 1964 in grave plot B2669 which she shares with her husband Ernest who died in 1940, her daughter Clarice Hallard who died in 1958 and her son-in-law Herbert Hallard who died in 1948.

Her elder daughter Gertrude May died in 1954 but she is not buried here in Radnor Street Cemetery.