Sometimes the death of a soldier received a lengthy obituary in the local newspaper. One such case was that of Thomas Tugby.

Swindon Soldier’s Funeral

Man Who Was Wounded at Ypres

Great sympathy has been extended to Mrs Thomas Tugby in the loss she has sustained by the death of her husband, which resulted from wounds sustained in action. Pte. Tugby was the son of Mr. and Mrs. J. Tugby, of 9 Gooch Street, Swindon, and was only 29 years old. He joined the Army at the age of 17 and became attached to the South Wales Borderers, and on taking his discharge, some years later, he entered the employ of the GWR Company and worked in ‘V’ Shop (Loco. Dept.) of the Swindon Works. On the outbreak of hostilities, he was called up on reserve, and went to the front with his old regiment. He was a participant in the heavy fighting at Mons and on the Aisne, and was wounded at Ypres by bursting shrapnel. On Nov. 1st he arrived in England with a batch of wounded, and was sent to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, Rochester, and hopes were entertained that he would recover from his wounds. On Wednesday last, however, his condition gave cause for anxiety, and his relatives were summoned. They were in time to see him before he died later in the day, and on Saturday his body was brought to his home in Swindon.

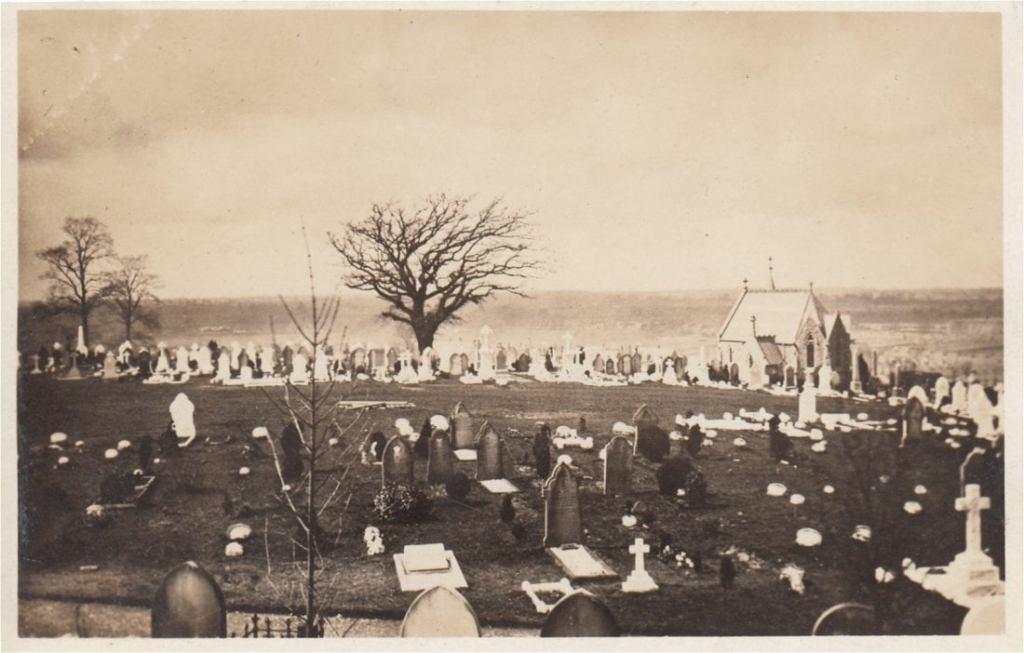

The remains were interred with full military honours at Swindon Cemetery on Monday afternoon. A large number of the Royal Field Artillery stationed at Swindon were present, and formed a guard of honour as the body was borne from the house in Gooch Street to St. John’s Church. The coffin was of plain oak and was covered with a Union Jack. The service at the church was impressively conducted by the Rev. W.H. Walsham How, who also officiated at the graveside. After the coffin had been lowered into the grave, the firing party fired three volleys and the “Last Post” was sounded by the buglers. The inscription on the breastplate of the coffin read:-

Pte. Thomas Tugby

Died Feb. 17th, 1915.

Aged 29.

The chief mourners were the widow, Mr. and Mrs. J. Tugby (father and mother), Mr and Mrs E. Lewis, Mrs. Lewis, Mrs Lewis (sister), Mr J. Tugby and Miss Lily Tugby, Mrs W. Turner and Mrs. J. Green (sisters) Sergt. J. Green (brother-in-law) Mr W. Turner (brother-in-law) Miss Ivy Lewis (sister-in-law), Mr. W. Lewis (brother-in-law), Messrs. J. Smith and A. Whale (representing deceased’s old shopmates), Mr C. Hill, Mrs. W. Gleed and Mrs Skeates (aunts) and Mrs W. O’Neil (cousin). Beautiful floral tributes were placed on the coffin from the widow, Mrs and Mrs Tugby, Mr and Mrs. Turner, St. Mark’s Ward of the Hospital at Rochester, Mr. and Mrs. J.A. Cooper, Mrs Dance and Mrs Gleed, ‘The family at 1 Linslade Street,’ Sergt and Mrs Green, Shopmates in ‘V’ Shop, Loco, Dept. GWR Works.

It is interesting to note that Sergt. Green was with deceased in the early days of the war. He has been invalided home, and is shortly to return to the front.

North Wilts Herald, Friday, February 26, 1915.

But after the funeral what happened to the family left behind?

His widow Alice was just 24 years old when he died. On April 22, 1916 she married for the second time. The wedding took place at St Mark’s Church, the groom was Thomas Henry Walter Archer, himself a widower.

The UK World War I Pension Ledgers and Index Cards 1914-1923 record that sadly Alice’s second husband died on September 10, 1925, also as a result of the war.

Quite what happened to Alice after this second bereavement remains difficult to discover. The impact of that terrible war can never be under estimated.

Tugby, T.

Private 7923 1st Battalion South Wales Borderers

Died 17th February 1915

Husband of A. Tugby of 9 Gooch Street

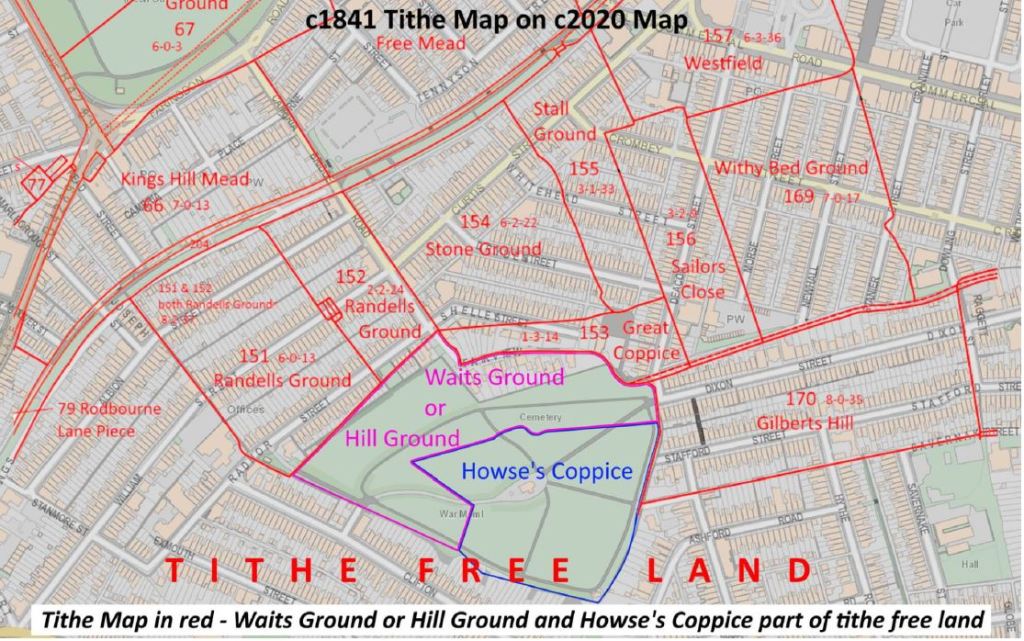

B1722 Radnor Street Cemetery

Tell Them of Us by Mark Sutton