In July 1939, as war became imminent, the Lord Privy Seal’s Office issued a number of Public Information Leaflets. Leaflet No. 2 contained information on ‘Your Gas Mask – How to keep it and How to Use It’ as well as instructions concerning ‘Masking Your Windows’ with the following advice:

In war, one of our great protections against the dangers of air attack after nightfall would be the “black out.” On the outbreak of hostilities all external lights and street lighting would be totally extinguished so as to give hostile aircraft no indication as to their whereabouts. But this will not be fully effective unless you do your part, and see to it that no lighting in the house where you live is visible from the outside. The motto for safety will be “Keep it dark!”

The ‘black out’ was yet another feature of wartime that impacted on everyday life. In the winter of 1940 these difficult conditions and icy winter roads resulted in a road traffic accident and the death of Charles Smart.

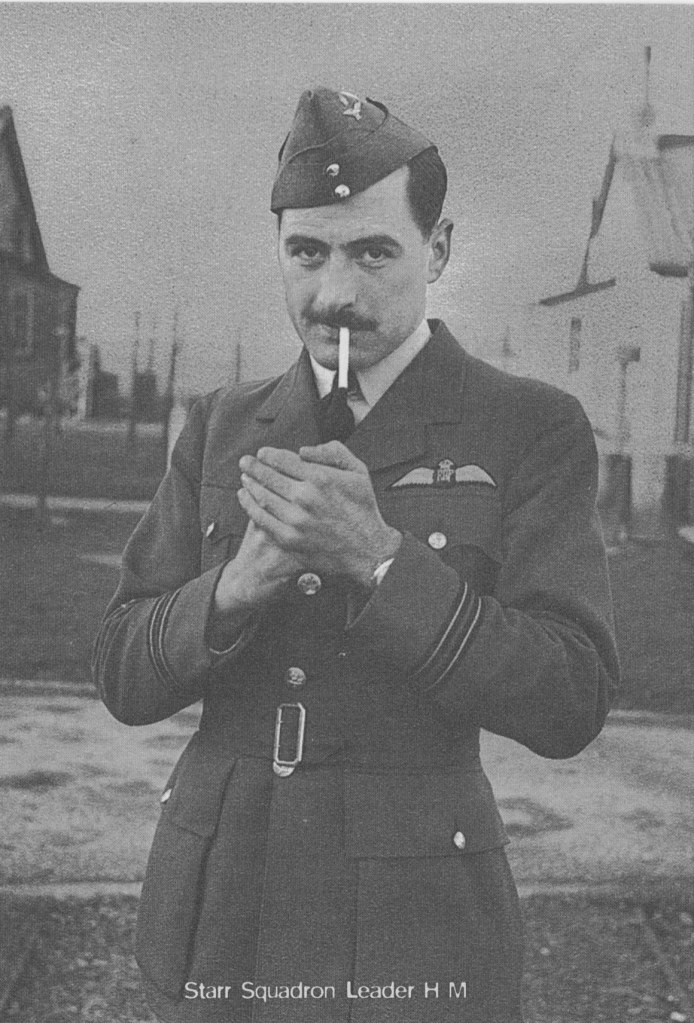

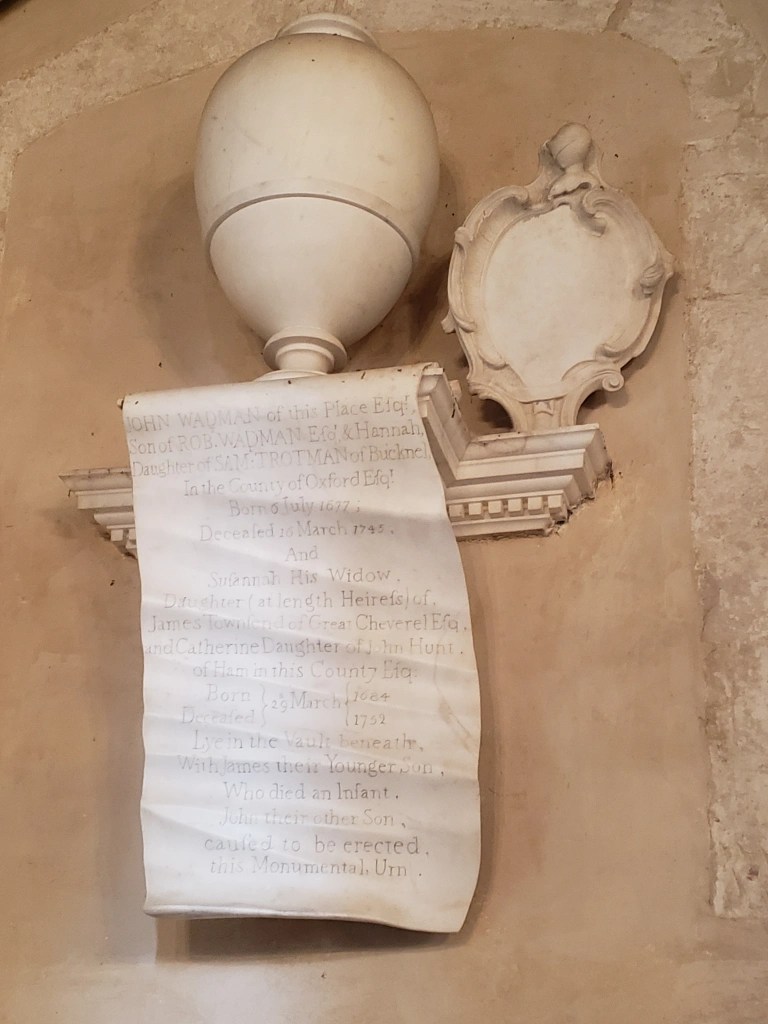

Image published courtesy of Local Studies, Swindon Central Library.

Killed in Black-Out

Inquest on Swindon Man

Against the wishes of his niece who thought the roads too treacherous for him, Mr Charles Smart, aged 68, a retired GWR employee, of 44, Curtis Street, Swindon, went out on Tuesday of last week to the Central Club. On his way home he was in the act of crossing the road when he was knocked down by a Corporation ‘bus receiving injuries from which he died in the GWR Medical Fund Hospital on Saturday night.

A verdict of “Accidental death” was returned by the jury at Tuesday’s inquest, conducted by the Wilts Coroner (Mr Harold Dale), and the driver of the ‘bus William John Snell was exonerated.

Mr Smart’s niece, Mrs Dorothy Kate Critchley, with whom he lived, said her uncle enjoyed good health, hearing and eyesight.

Dr Alister McLean said the cause of death was shock following injury to the brain due to a blow on the head.

Reasonable Speed

Walter Fred J. Ockwell, 10, Milton Road, Swindon said that last Tuesday night about 10 o’clock, he was in Curtis Street and just before reaching Whitehead Street he saw a form in the middle of the road. The form was not moving. When about 30 feet away he shouted to the object. A ‘bus came along but the object did not appear to move until the ‘bus was almost on top of it. As the ‘bus swerved to the right the object moved to the left. The ‘bus was almost in the middle of the road, and was being driven at quite a reasonable speed.

When he reached the spot, the driver and passengers were getting out of the ‘bus. The object proved to be a man lying a little to the centre of the road. It appeared as if the ‘bus had pushed the man forward. Witness said that as the man stood in the road he faced the direction from which the bus came.

Private James Lewis Warburton said he saw Smart leave the pavement and walk towards the centre of the road, where he stood still. He thought Smart was going to stop the bus, and he did not see him slip.

Driver’s Swerve

The bus driver, William John Snell, described it as a very dark night, with bad road conditions. When he first saw the figure in the road it was very close to the bus and well into the road. He immediately applied his brakes and swerved to the offside, but, owing to the condition of the road, the bus slipped along a little further, and the nearside headlamp struck the man, who was wearing dark clothing.

Questioned by his solicitor (Mr S.G.G. Humphreys), Snell said that had Smart remained where he was when he first saw him, the swerve would have avoided him.

The Coroner suggested that it might be that Smart found the road so slippery that he was afraid to move.

Sympathy was extended to the relatives by the Coroner, and by Mr Humphreys on behalf of the Corporation and the driver of the bus.

North Wilts Herald, Friday, 9 February, 1940.

Image published courtesy of the Dixon Attwell Collection, Local Studies, Swindon Central Library

Charles Smart 69 years of 44 Curtis Street died at the GW Hospital and was buried in a public grave, plot C149 on February 8, 1940.