Some years ago, I attended a talk about life ‘inside’ given by Miss Lorna Dawes at the Central Community Centre. The talk was hosted by The Railwaymen’s Association who had been meeting regularly following the closure of the Works in 1986 with guest speakers delivering talks about all things railway related. To those of you unfamiliar with Swindon railway jargon ‘inside’ refers to working in the railway works and it has to be said it was a rare occasion to hear a woman talking about such a subject. The only other woman I had ever heard give such a talk was social and railway historian, Dr Rosa Matheson.

Lorna sat at a table at the front of the hall and without the aid of any photos or slides or whizzy technical gizmos, spoke about her time in the Works. Lorna had a small sheaf of notes in front of her and thus armed she set about informing and entertaining her audience. Of course, she knew all the railwaymen present and exchanged quips and jokes with them during the course of her presentation.

I soon gave up trying to take my own notes and just sat back and listened to this amazing woman.

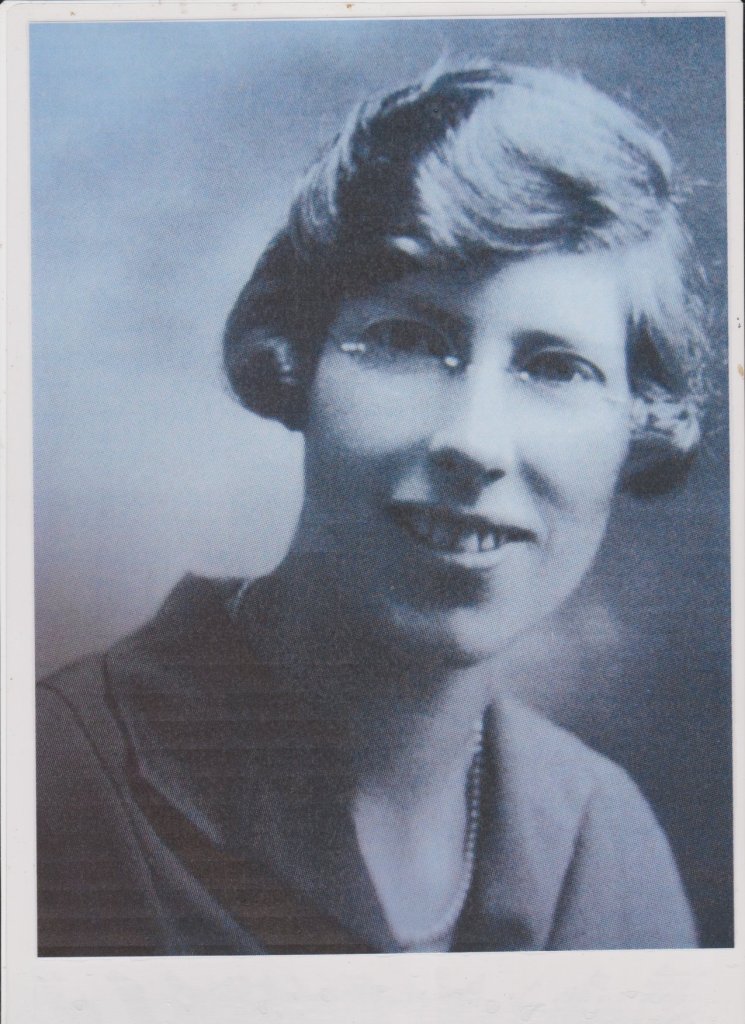

Lorna was born on March 23, 1931, the daughter of iron moulder Albert Edward G. Dawes and his wife Mona and lived all her life in Tydeman Street, Gorse Hill. She started work as a messenger in the Works in April 1945, aged 14 years old.

Lorna had taken lessons in shorthand while still at school and later attained a certificate for 120 words per minute at evening school. However, her first job as a messenger presented few opportunities to sit down and take notes. She had to quickly learn her way around the vast railway factory, which in the 1940s covered 326 acres. Walking through the tunnel to access all areas was obviously the bane of the lives of the young women where the sludge and filth ruined their stockings.

Most days included a trip to Grays [bakery] in Bridge Street for small lardy cakes for the office staff and to collect the milk and make the drinks to go with those lardies.

Then there was collecting the absences book from the tunnel entrance, delivering the bank bag to London Street, taking messages to Bristol Street, Park House and the laboratory housed in the old school.

She then went on to describe the staff office work, which involved everything from filing accident reports in Park House to duties in the Booking Office and collecting rent owed on the company houses.

She mentioned the double length typewriters used to type charts of salaried staff promotions and wrote: “I enjoyed manipulating lines of names into spaces.” She was also able to fix minor repairs on the typewriters until the mechanic came from Bristol.

Lorna participated in the busy social life of the Works, playing tennis and badminton, representing the offices in tournaments.

Lorna was one of the earliest and most enthusiastic subscribers to Swindon Heritage, a local history magazine published between 2013-2017 with which I was involved. I would have loved to have told her story in the magazine but Lorna wasn’t ready then.

It was with great sadness that I learned about her recent death and regret that I had not captured her memories.

And then I had the good fortune to exchange emails with Yvonne Neal, a member of the Swindon branch of the Wiltshire Family History Society. Yvonne had been in touch with Lorna’s brother and quite remarkably the notes from that talk survive.

The handwritten notes cover more than 11 pages and include not only the big events but the more personal ones too, those of Christmas’s in the offices, weddings, birthdays and babies.

And then she wrote: “My story was due a book “Tempus” pub. but interviewer left post. Didn’t get published.” Perhaps she felt so let down she wasn’t going to go through the performance again with me.

I wish I had had one more conversation with Lorna, to thank her for her support and enthusiasm during the publication of Swindon Heritage and to persuade her to tell her story again. I’ve done my best here.

You may also like to read:

Lorna Dawes in her own words – Pt. 2