The re-imagined story …

Mr King held a whole school assembly the day the news was published. William Hall had been awarded the DSM, the Distinguished Service Medal for Honours for Services in Action with Enemy Submarines.

William Hall hadn’t been a pupil at Jennings Street School. By the time the school opened he was working as an Engine Fitter ‘inside.’ It was this job that made him ideally suited for the role of Engine Room Artificer.

We all knew the Hall family. They lived at 77 Jennings Street. My auntie lived opposite them at number 4. Everyone knew everyone in Rodbourne in those days. We all shared in the glory of one of our own being so honoured.

Less than a year later we all mourned his death as well. He wasn’t killed in battle. To expect another act of heroism from one man would be too much. William Hall died of pneumonia and pleurisy – another form of drowning, only not at sea.

Perhaps Mr King held another assembly. I don’t know, I had left school by then and was waiting to start my own apprenticeship in the Works. I was too young to serve, much to the relief of my mother.

By 1918 everyone knew of someone who had died in the war. It was like that in Rodbourne. But not everyone knew someone who had won the DSM.

The facts …

William Jasper Hall was born on November 6, 1888, the third child and second son of William Charles Hall and his wife Sarah. At the time of the 1891 census the family were living a 30 Jennings Street, Rodbourne on the very doorstep of the Great Western Railway Works. The family continued to live at various houses in Jennings Street.

William Jasper followed his father into the Works, entering the GWR Employment and a 7 year Fitters apprenticeship on his 14th birthday, November 6, 1902.

He enlisted in the Royal Navy on March 20, 1916 and completed his training period on the Victory II as an ERA (Engine Room Artificer) on April 28, 1916. His character and his ability were both described as Very Good.

His naval records reveal that he served on HMS Cormorant, a receiving ship at Gibraltar where he joined the Freemasons at the Masonic United Grand Lodge in 1916.

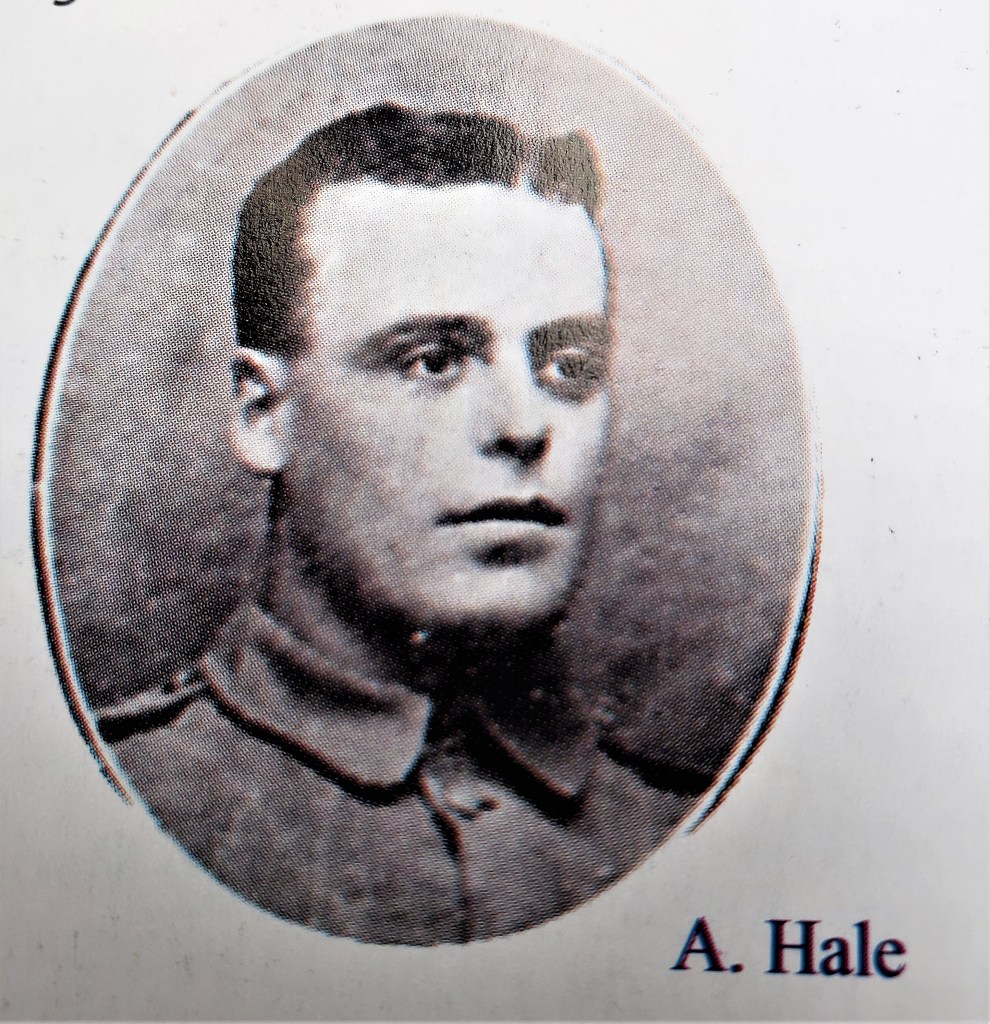

In September 1917 William was awarded the DSM (Distinguished Service Medal) for Honours for Services in Action with Enemy Submarines.

By 1918 he was back on Victory II, a shorebased depot for Royal Navy Divisions at Crystal Palace and Sydenham. From here he was admitted to the Royal Haslar Hospital in Gosport where he died on September 14, his cause of death pneumonia & pleurisy.

Family recollections are that William caught the Spanish Influenza with a poignant postscript to the story. His mother Sarah visited the hospital where she was able to care for her son during his final days. Sadly, Sarah contracted the ‘flu and died two weeks after her son.

William was buried in plot E7464 on September 19. His mother Sarah was buried in the same plot on September 28. William Charles Hall died in 1939 and joined his son and wife. Jessina, William Jasper’s elder sister, died in 1949 and was buried in the plot with her brother and her parents.

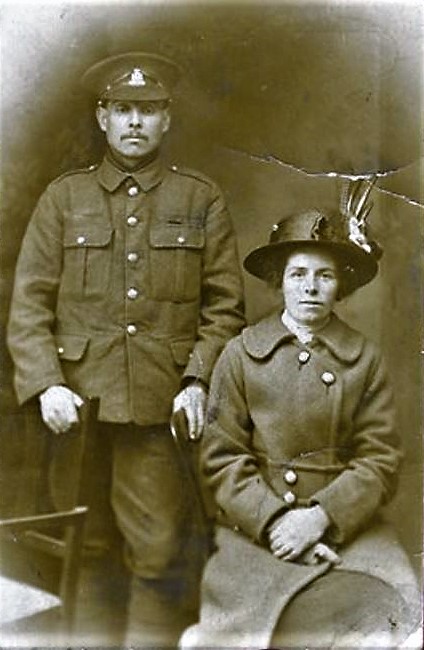

Family photographs are published courtesy of the Hall family.

Originally published February 21, 2022.