The re-imagined story …

Mr Hustings gave me a job when no one else would.

I’d returned from the war pretty much fit for nothing. But my wounds were not obvious. I had not lost a limb, I was not scarred or hideous to look upon.

I suffered from being subjected to heavy shelling, day after day, week after week, from living on the edge of terror.

Others seem to return home unaffected from the hell they had endured, although I would question that. I don’t think any returning soldier was the man he had been when he left for the war. Even now, twenty years later, you can see the men ravaged by their experiences. The men who drink too much, the men whose temper is easily ignited, the men who retreat into silence. We all carry our wounds, the obvious ones and the hidden ones.

Mr Hustings must have wondered if he had been ill advised employing me. I’m sure plenty of his other workmen must have thought so to. At first I couldn’t go up a ladder, but there were plenty of jobs I could do at the yard. Gradually my life became more of the now and less of the then. My confidence grew, my health improved and I began to pull my weight in the firm.

I shall add Mr Hustings to the memory of those others I mourn. He gave me a job when no one else would, he gave me back my life.

The facts …

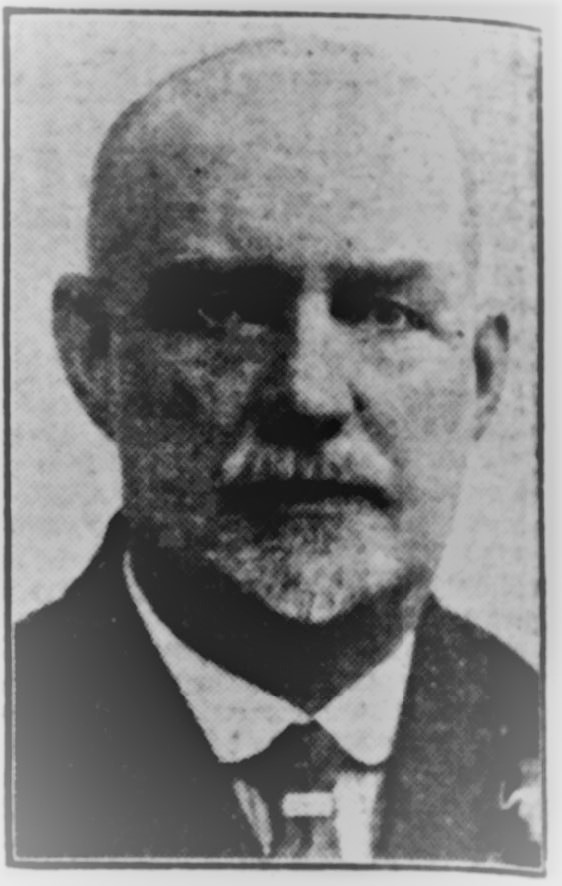

With just a week left to complete his term of office as Mayor, Councillor H.R. Hustings died suddenly at the Victoria Hospital on Sunday, October 27, 1940.

A tough speaking, no nonsense Labour politician, Henry Russell Hustings, Swindon’s 40th successive Mayor, took office on Thursday, November 9th 1939 as the town got to grips with the black out, air raid warnings and wartime restrictions.

A former trade union organiser for the National Union of Vehicle Workers and the Transport and General Workers’ Union, Henry had enjoyed a varied working life and the Swindon Advertiser styled him as the ‘Jack of All Trades Mayor.’

His first job was with a firm of agricultural engineers in Dorset followed by stints as a traction engine driver, shop assistant, porter, engine driver in a laundry, miner, stoker, baker and in 1939 he was a window cleaning contractor.

Henry was born in 1883 in the Dorset village of Hilton to John W. Hustings and his wife Susan. In 1903 he married Alice Maud Ball and the couple had four children.

A member of the Labour party since 1919 Henry began his political career in Devizes in 1921 where he was the first Labour member of the Town Council. By 1927 he was living at 38 Regent Circus, Swindon and represented the West Ward on the Swindon Town Council.

Councillor Hustings was a founder member of the Unemployed Association, launched at a time when Swindon had more than 5,000 unemployed. In 1939 he was President of both the Swindon branch of the Labour Party and the Swindon Trades Council. He also served on the Management Committee of the Swindon Co-operative Society, the Council of Social Service, the local Food Control Committee and the Western Area Federation of Trades Councils.

On August 22, 1940 Henry launched Swindon’s own Spitfire Fund. The aim was to raise £5,000 and in less than a week the fund stood at £245. By October Swindonians had raised £3,300 and were well on the way to achieving their target. Donations came from across the Swindon and district area. Two little girls sold some of their toys and gave the 8 shillings they had raised to the fund while Kingsdown brewer J. Arkell & Sons presented the Mayor with a cheque for £100.

At the time of the Mayor’s death the fund stood at £3,956, just over £1,000 short of its £5,000 target.

“The fund had a very good start, but it seems to have slowed down during the last two or three weeks,” said Mr Raymond Thompson, director and general manager of the Swindon Press who was behind the last desperate drive to complete the fund. “We owe this and a lot more to our late Mayor.”

In just seven days generous Swindonians had donated £1,352 to complete the project inaugurated by Henry Hustings. A cheque for £5,308 was presented to Col J.J. Llewellin, Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Aircraft Production by Swindon’s MP Mr W.W. Wakefield in January 1940.

Henry’s death at the age of 57 followed recent surgery from which it was thought he was making a good recovery, and came as a great shock to fellow members of the Council.

The funeral service conducted by Major W.J. Hills of the Salvation Army took place at the Mission Hall followed by interment at Radnor Street Cemetery.

“Representatives of practically every industrial and social organisation in the town and district took their place in the cortege, and also paid their last tribute at the graveside at Radnor Street Cemetery,” reported the Advertiser.

“The public life of Swindon will be much poorer by the passing of Councillor Hustings,” Mr G.A. Marshman, presiding magistrate said paying tribute to a man who had devoted his life to the underdog – Swindon’s Jack of All Trades Mayor Henry Russell Hustings.

Surprisingly there is no headstone to mark Henry’s grave.