Following the horrors of the First World War an increasing number of women began to take their place on the political stage at both national and local level.

Lydia Fry was already serving as a member of the Swindon and Highworth Poor Law Board of Guardians, before standing at the Town Council elections in December 1919.

Lydia was born in 1871, the fourth child and only daughter of agricultural labourer Richard Wilson and his wife Fanny.

She spent her childhood at Buscot, Berkshire but by 1891 Richard, Fanny and Lydia were living at 35 Bright Street in Gorse Hill. Richard worked as a platelayer labourer on the railway and Lydia was a shirt seamstress.

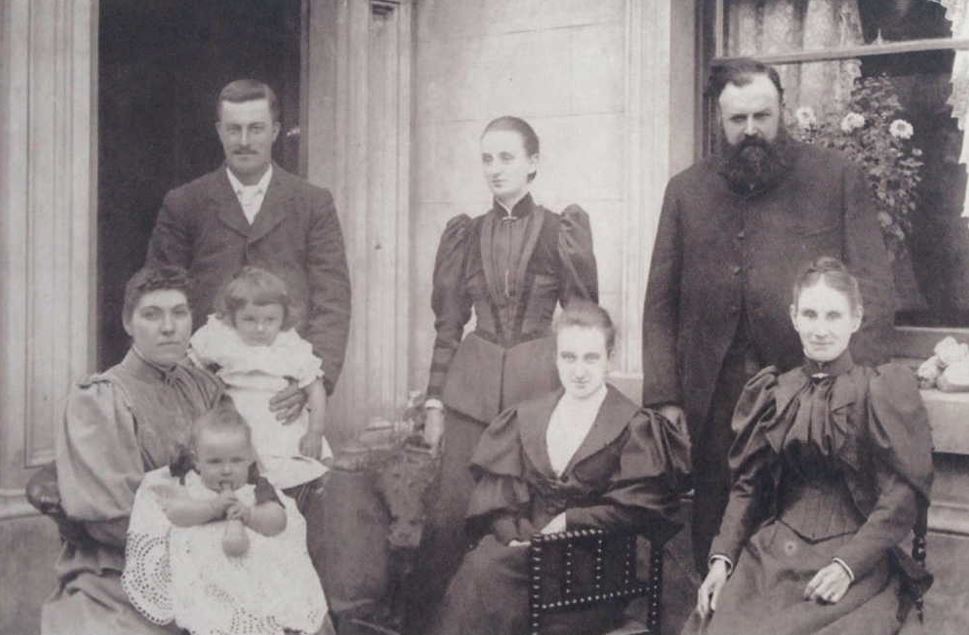

In 1892 Lydia married Silas Fry. Their first daughter Esther was born in December of that year. A second daughter Miriam was born in 1893. In 1901 the family lived at 110 Chapel Street and from around 1911 until the death of Silas in 1925 at 71 Cricklade Road.

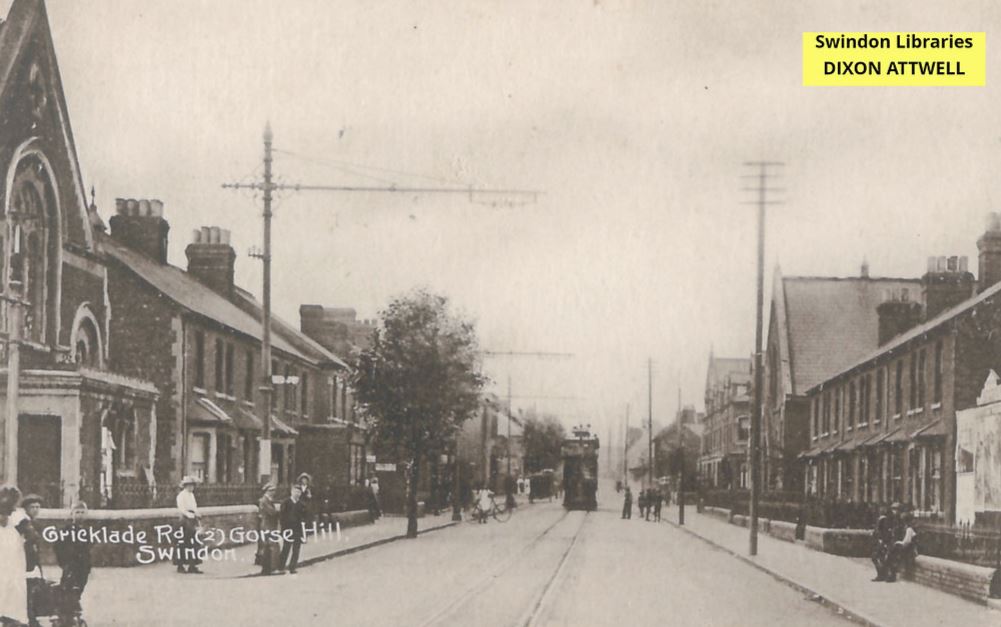

Image of Cricklade Road, Gorse Hill published courtesy of Andy Binks, Local Studies, Swindon Central Library.

When Silas died in 1925 the North Wilts Herald published a fulsome obituary detailing his many accomplishments. However, when Lydia died on April 24, 1941 only a brief account of her funeral was published in the same newspaper. There was no mention of her political career or her public service. Fortunately, in 1924 the North Wilts Herald published this account of Lydia’s life and work, written by W. Bramwell Hill.

For Services Rendered

Mrs Silas Fry’s Good Record

By W Bramwell Hill

Public service of all kinds has its times of difficulty, and, frequently, of irritation. You are not your own. You are bought with the price of the lurid light of criticism, half truth, misunderstanding, and misrepresentation. Happily that is not the only state. Such work does on occasion know a transition into the realm of tangible reward, even though the true reward is in the race well run, and the game well played, with patience and imperturbability of fine motive as the fairy hand-maidens of high endeavour. For what they receive in the unalloyed joy of doing a great work, whatever the sphere, multitudes toil on and in their toil rejoice.

To such a band the subject of our brief sketch this week belongs.

Mrs Silas Fry, of Cricklade Road, Gorse Hill, wife of Councillor S. Fry, is a lady well known for a splendid record of faithful work in her own area. Her chief activities have been in connection with the Swindon and Highworth Board of Guardians (of which she has been a member for some 17 years, I believe) and the Cricklade Road Primitive Methodist Sunday School. It is quite possible – yea, it is more than probable – that the energy for the one task has been found in the service of the other. In the realm of the Sunday School she has put in no fewer than 26 years of successive service, and during the recent Sunday School rally held amid the sylvan setting of Bassett Down House (by kind permission of Mrs Arnold Forster) Mrs. Fry was presented with a diploma of honour, the gift of the Connexional Sunday School Union.

Mrs Fry’s record, by the way, is largely confined to one school – Cricklade Road. In young people’s work, in the choir, the Christian Endeavour movement, as a representative to the Quarterly Board, as well as being a most effective speaker, she is well known. In these times of women’s recognition a certain appropriateness is found in the projection of the good record of Mrs Fry, who, in co-operation with her husband, has put in a vast amount of unostentatious service for the public weal.

North Wilts Herald, Friday, June 6, 1924.

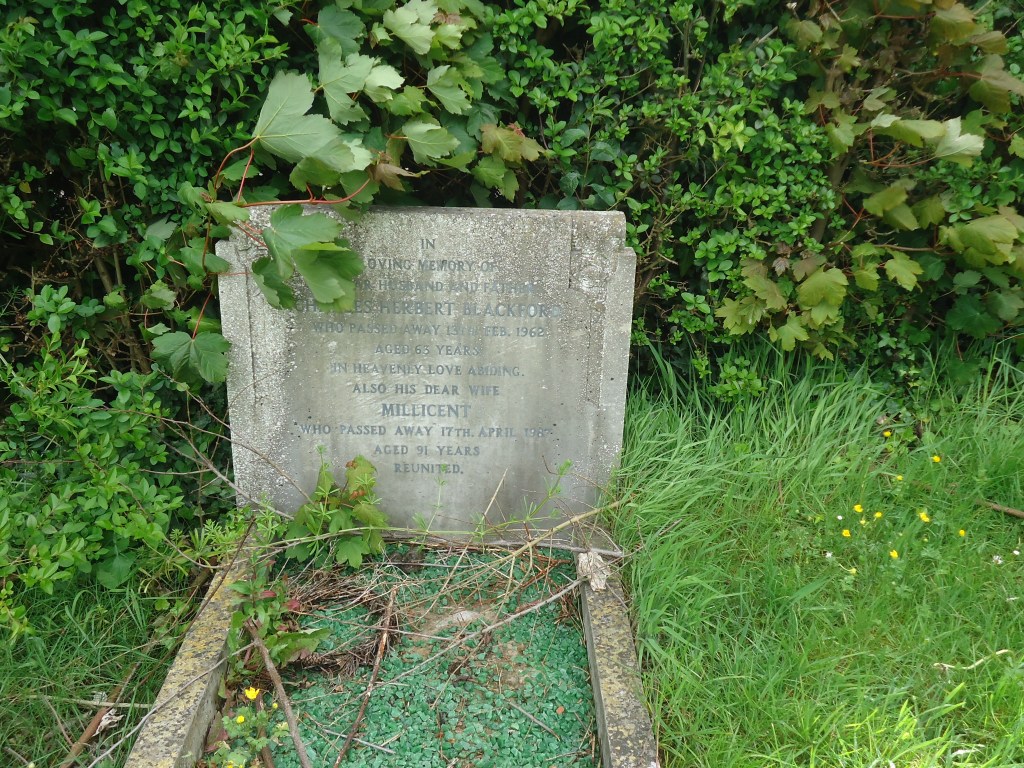

Lydia Elizabeth Fry died aged 69 years at 24 Dudmore Road. She was buried on April 27, 1940 in grave plot D808 she shares with her husband Silas.