The re-imagined story …

I was in my last year at school in 1983, trying to decide what I wanted to do with the rest of my life. I knew I definitely didn’t want to go into the Works like my dad, but then it looked as if the days of the mighty railway factory were numbered anyway. It had to be something interesting, something exciting.

What I would really have liked was to join XTC. For those of you who missed the 70s and early 80s for whatever reason, there was punk and prog pop, new wave and New Romantics and, if you came from Swindon, there was XTC.

What was it about them I liked? Was it their sense of fantasy and psychedelic wonderment, to steal a quip from founder member Andy Partridge? Or was it because they were cool and came from Swindon? It was exciting to know that the members of the band had walked the same streets I had. As Andy once said, ‘Swindon was a bit shit but there are worse places and everyone has to come from somewhere.’

I knew I didn’t have any musical talent, but I was sure there was a job I could do as part of the XTC entourage; a technician or press officer, or maybe a photographer, something like that.

In the summer of 1983 word went around school that the members of XTC would be filming a music video somewhere in Swindon for a track on their upcoming album. It came as no real surprise that they should chose the old cemetery, just the crazy kind of thing they would do. Here was my opportunity.

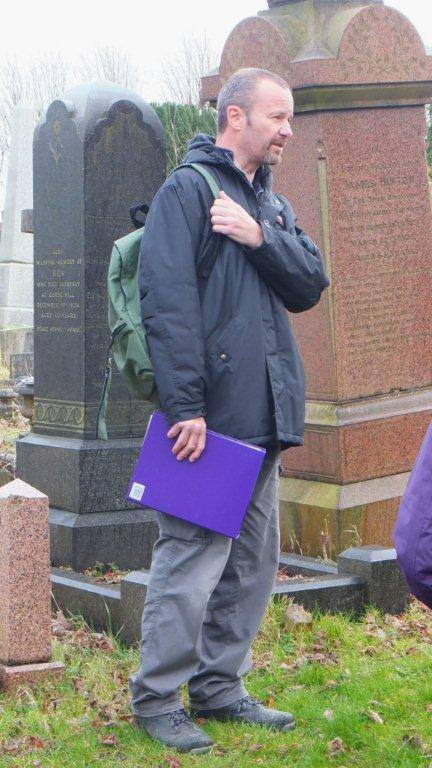

There was no special treatment for the guys the day they filmed at Radnor Street Cemetery. I was among a handful of fans there and as long as we kept out of the way, no one seemed to mind.

This would be my first foray into photography. I had a goodish camera, a present from my granddad. I got what I anticipated would be a couple of good shots of Colin wandering among the graves, looking contemplative and rock starry and several of Dave and Andy dressed in military uniforms and misbehaving in the background.

The cameraman spent a long-time getting shots of individual headstones and memorials, in particular a magnificent guardian angel, which became the opening shot of the video.

It was several weeks before my film came back from Boots the Chemist.

Even now, more than 30 years later, I can remember the heart squeezing disappointment as I opened the envelope and looked at the prints. My first photographic assignment, a total disaster. But as Colin blurred across the foreground, an image appeared in the background, close to the old mortuary building. At first, I assumed it must be the indistinct image of another fan, out for a glimpse of the band, but I began to see the outline of what looked to be a soldier, head bowed, wearing an old-fashioned army uniform and a tin helmet. He carried a kit bag on his back and held a rifle at his side. It was the silhouette of a Tommy from the First World War, there, but not there.

No one could see what I could see, not my parents, not my friends. And after a time I could no longer see the invisible soldier.

In Loving Memory of Name was written by Colin Moulding, but it turns out it wasn’t among his favourites in the band’s back catalogue. He was to later describe it as being about “moping ‘round a graveyard and just remembering the lives of the people there.”

It was several years before I returned to Radnor Street Cemetery. I stood in the place where I had watched Dave Gregory and Andy Partridge and taken my photographs. And then I walked around to the old mortuary building where I imagined I had seen the First World War soldier, there but not there.

I noticed for the first time the official Commonwealth War Graves headstone, discoloured and dirty. The inscription read Sapper A.C. Ellis, Royal Engineers, 24th September 1918 Age 19.

The Mummer album came after a long XTC hiatus. I recently returned to the cemetery after my own period in the wilderness. The guardian angel still looks good. And someone has propped up against the war grave headstone a small photograph of the young soldier.

There, but not there. Photograph published courtesy of Andy Binks.

The facts …

Arthur Cecil Ellis was born in Swindon in 1899 the only surviving son of Thomas George Ellis, an engineer in the railway works, and his wife Annie Maria. He was baptised at St. Mark’s, the church in the railway village, on February 20, 1899 and for all his young life he lived at 38 Farnsby Street.

Arthur Cecil Ellis served in ‘C’ Company of the 6th Reserve Battalion of the Royal Engineers. The 6th Reserve Battalion was located at Irvine and was formed in January 1918 from what had been the reserve Field Companies grouped in Scottish Command.

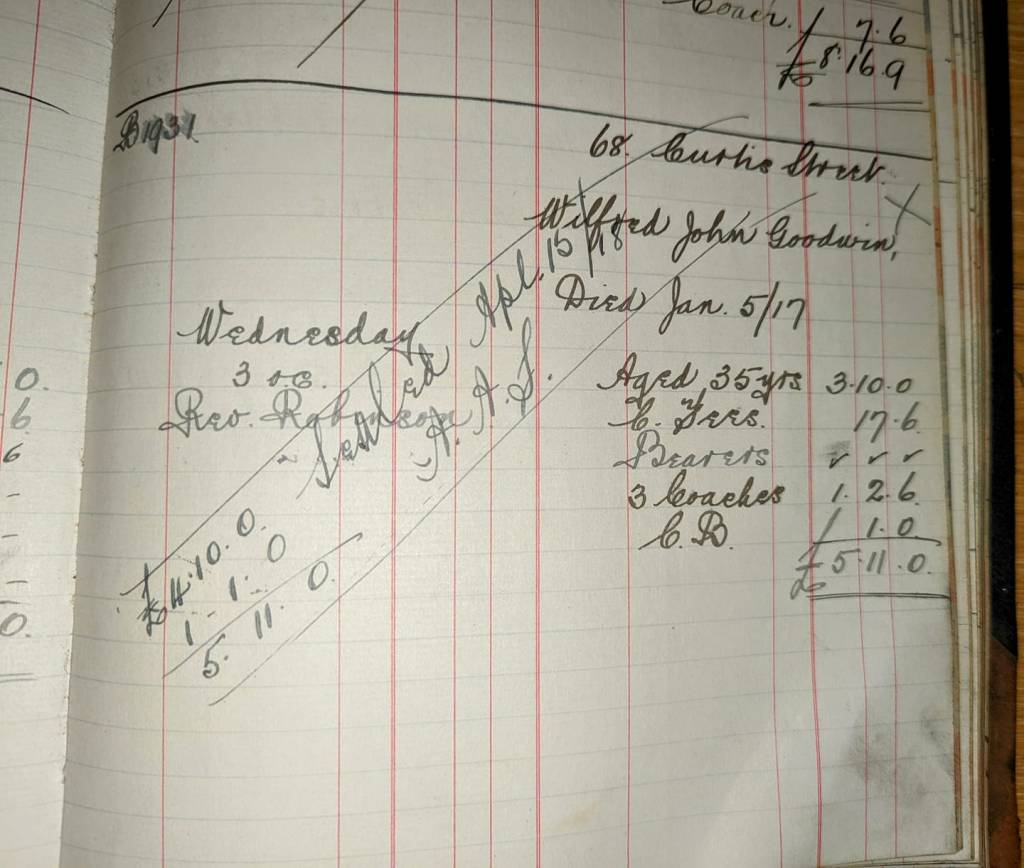

Arthur died on September 24, 1918, according to the UK Register of Soldiers’ Effects 1901-1929 at Kilmarnock Hospital where he had £3 2s 9d (about £3.20) in pay owing to him, which would go to his mother Annie.

His body was returned to the family home at 38 Farnsby Street and he was buried at Radnor Street Cemetery on October 1st.

More than 50 years later, in the summer of 1969, Arthur’s sister, Dorothy, who worked as a dressmaker when Arthur went to war, died aged 74 and was buried with the teenage brother lost during the final weeks of the First World War.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qC-PxpywwjA&list=RDqC-PxpywwjA&start_radio=1