The re-imagined story …

Mr Sykes asked me to sing All Things Bright and Beautiful. He listened very carefully; his head tilted on one side. There was a brief pause after I stopped.

“Well Ada,” he said, “I’m sure we can find a place for you in the chorus.”

I was so excited I could have given him a big hug, but that would have been entirely inappropriate. You didn’t hug a gentleman like Mr. Sykes.

My ma said I was born to sing. She said that I sang even as a baby in my crib. “You never wailed or screamed like the other babies,” she said, “you sang.”

I’ve been singing ever since. I especially love to sing in church. My favourite hymn is Rock of Ages, I love the rise and swell of the music. And I sing at my work, but I try not to be too enthusiastic as Mrs Morse has delicate hearing and she usually asks me to close the green baize door while I’m in the kitchen.

But I had never sung in public before and I never dreamed I would one day stand on the stage at the Mechanics’ and sing before an audience. I could scarce believe Mr. Sykes might even consider me.

It was my best friend Polly who suggested I audition for the chorus in the Mechanics’ Institution pantomime that year – Babes in the Wood, or Harlequin and the Cruel Uncle.

Opening night was just days away and this was to be our dress rehearsal. “Let’s put you next to Letitia, just follow her lead,” Mr Sykes had said at our last rehearsal. Letitia Jones was one of the principal singers in the chorus. She had a beautiful voice, a bit on the quiet side, I always thought, but melodious none the less.

Polly was waiting in the wings when I arrived. She was in conversation with Letitia and had her back towards me, but I could hear them talking as I approached.

“I hope Ada Firebrace doesn’t stand next to me again. She quite puts me off,” said Letitia.

“I never expected Mr. Sykes would engage her,” I heard Polly say. “I hoped he might tell her … you know … tell her what an awful voice she has. Then perhaps she would stop singing morning, noon and night.”

I stood stock still. Letitia had seen me walk across the stage and was grimacing and nodding at Polly with the intention of warning her that I approached. It was too late.

I never spoke to Polly again and I didn’t take part in the Mechanics’ Institution pantomime that year either. But I did save up my pennies and took some singing lessons with Mrs Sykes.

Ma says my voice is more beautiful than ever now. I have no desire to sing before an audience anymore, but I will always have kind memories of Mr Sykes.

The facts …

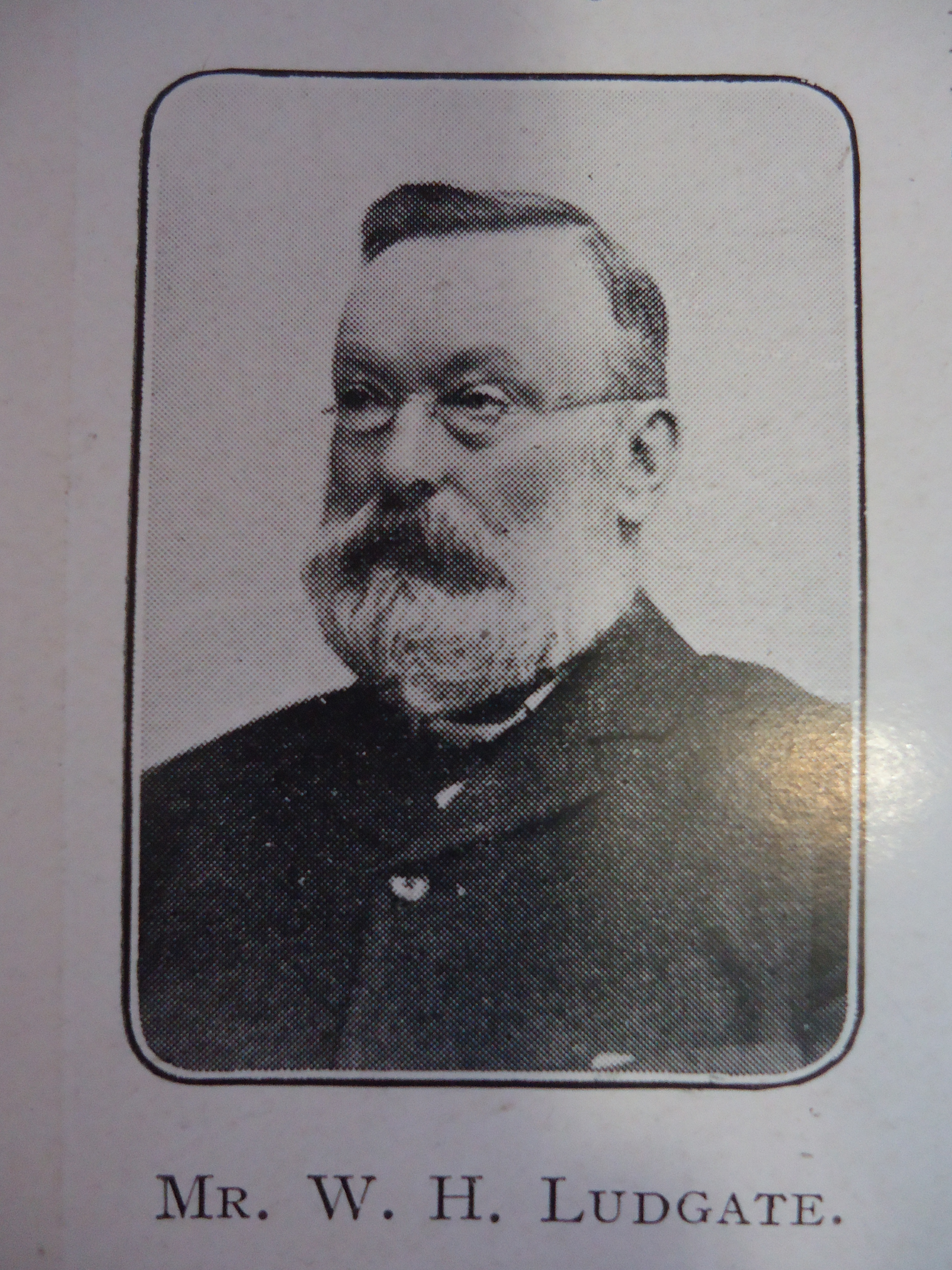

The Late Mr Albert Sykes

In accordance with the recommendation in the report, Mr Spencer proposed that a large portrait be obtained of the late Mr Albert Sykes, and placed in the Reading Room. Mr Sykes, he remarked, was a man who in his day and generation did a great work for New Swindon, and many men had been indebted to him for his musical tuition. Mr. Sykes was a useful man on the Council of the Institute, a capital librarian during the time he held that position, and he was also the father and founder of music in Swindon.

Mr A.W. James seconded the proposition, which was carried unanimously.

Mr Morris said he was pleased to know that the Council were thus going to recognise Mr Sykes’ services, and he hoped the same course would be adopted with regard to the late Mr J.H. Preece and the late Mr F.G. O’Connor.

The Swindon Advertiser, Saturday, May 5, 1894.

The two Sykes brothers were born in Leeds – Albert in 1823 and Joah in 1824. On the 1841 census they are living in Hunslet where their father John worked as a surveyor of roads. Albert was working as a mechanics’ apprentice while Joah was a potter’s apprentice.

Albert began work as a fitter and turner in the GWR factory in September 1847 later working as a shop clerk.

The 1851 census shows Joah still living in Hunslet with his wife and baby daughter. He is working as a whitesmith (someone who works with tin). Joah joined his brother in New Swindon around 1853 where he worked as a blacksmith in the railway factory. At the time of the 1861 census he is living with his wife and their five children at 1 East Place in a property they share with Peter Vizard, his wife and two daughters; Thomas Toombs, his wife and their three children and a lodger by the name of Jeremiah Walker!

By 1871 Joah and his family are living at 25 Reading Street, which remained his home until his death in 1910.

On first coming to New Swindon Albert lived in Westcott Place. Then he spent 20 years living in Fleet Street before moving to Victoria Road where he and his wife opened a music school.

Both Joah and Albert were talented musicians. Joah played the oboe and both brothers were involved with musical events at the Mechanics’ Institute where Albert conducted the Mechanics’ Institutes’ Choral and Orchestral Union.

The two Sykes brothers are typical of those early settlers who left their home, their family and friends to move to New Swindon and once here immersed themselves in the life of the community.

Albert died on February 27, 1894. His funeral took place on March 3, 1894 and he is buried in plot E8362 with his wife Mary Hannah, son Albert and nephew Herbert Francis Sykes – Joah’s son.

Joah was elected to the Council of the Mechanics’ Institution in 1870. He was a member of the Liberal Association with a reputation for being a radical and he was a member of the Methodist Chapel in Faringdon Road.

Joah died on February 17, 1910. He is buried in plot E8364 close to his brother Albert, with his wife Ellen and two of their daughters. Emily is described on the 1901 census returns as being an ‘imbecile from birth’.