In the Summer 2016 edition of Swindon Heritage Noel Beauchamp told the story of the man who drove the GWR’s first train and was a personal friend of no fewer than three railway pioneers, and lived and died in the Railway Village. Here is an extract from that article – Colourful career of the man they couldn’t sack.

He was a personal friend of Sir Daniel Gooch, but there is no getting away from the fact that Jim Hurst was a difficult character.

Official GWR reports reveal a catalogue of arguments, rows, conflicts, accidents and even fights throughout the career of the man who became the company’s first driver.

His first accident occurred in 1836 while he was still working for the Liverpool & Manchester Railway.

Sacked, he was almost immediately hired by Daniel Gooch, then Locomotive Superintendent of the GWR – although when recounting the story to the company magazine, many years later, he gave an entirely different explanation of the circumstances.

He also told the GWR magazines that he had had “some very narrow escapes”, including in 1855 when the engine he was driving exploded and “I was blown up through the air and my mate was killed.”

The first blot on his GWR career came in 1840 when he was reported for driving his engine in a careless manner and colliding with the engine Wildfire, which was severely damaged, along with the tender of the engine he was driving.

The following year he was reported for refusing to work a train with a particular guard he had taken a dislike to: a policeman called Burton.

Jim was fined £2.

In 1842 he was accused of taking passengers for a joyride, and charging them for the privilege.

‘Sundry policemen’ reported him for the offence, one claiming Jim was “in the habit of taking people on the engine to and from Kemble and Cirencester, as many as three at a time … but stopped the engine about three-quarters of a mile from Cirencester and set them down.”

Not for the last time, his friend Gooch stepped in, and Jim was able to produce a leter from one of the ‘passengers’, denying that any payment was made.

So he was off the hook.

The same year he was involved in a serious accident at Kemble in which an engine called Meteor overturned, and the passenger train that Jim was driving ended up in a siding. He later claimed it was caused by a switchman.

In 1854 he was in trouble again.

This time he threatened to take a policeman into a nearby field for a fight and after the matter came before the GWR Board, they fined the hapless driver ten shillings (50p).

Two years later it looked like Jim’s employment with the GWR was over when the Board sacked him for fighting with a porter at Newnham.

However, Gooch had been away at the time, and 10 days after his friend’s sacking he intervened and Jim was reinstated.

At the hearing it was noted by one GWR man that “You can do nothing with Hurst. He follows Gooch’s order.”

Then, in 1858, Jim found himself fined another £3 for damaging a horse box after running past a danger signal at Farringdon Road, London.

Another bad year in Jim’s career was 1859, when he ran into two engines in two separate incidents.

First he hit the tender of Dart, a Firefly Class loco, for which he was fined 14s 3d (71p), then he wrecked the buffers of Alma, an Iron Duke Class engine.

This time he was ordered to pay the cost of repairs, which would have been carried out at Swindon and amounted to £3 6s 10d (£3.34).

Then, in August 1862, there was another incident, the details of which are not recorded. But it was serious enough for him to be removed, at last, from the footplate, and permanently transferred to Swindon Works. Even Gooch seemed unable to save Jim’s driving career this time, but he still had a job – and would eventually receive a generous pension.

Although drivers were often moved around the GWR, in Jim’s case it seems successive managers at Paddington, Taplow, the Forest of Dean, Cirencester, Totnes, Swansea and Leamington all found that if they couldn’t dismiss him, there was always the option of transferring him to another part of the vast network.

For the last 30 years of his life Jim was a Swindonian, living in the Railway Village and earning, through his pension, more than most of the general workers ‘inside.’

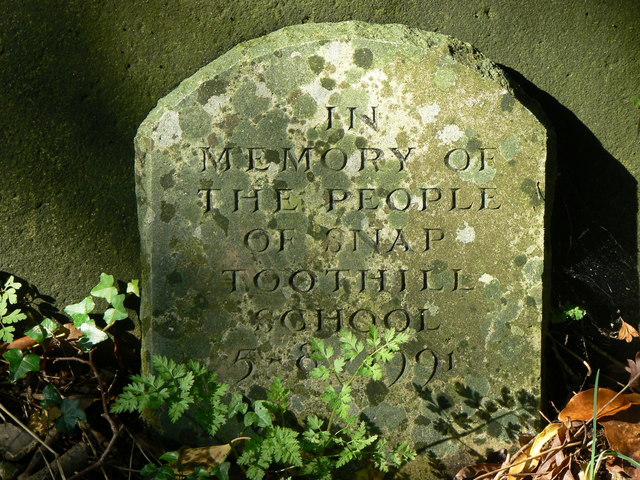

Time ran out for him in August 1892 when he died in his 81st year, and he was buried with his wife in Radnor Street Cemetery.

Strangely, considering he and his family would have been able to afford a memorial, the grave is unmarked, and was only recently rediscovered by the Swindon Heritage team. (Summer 2016).

The burial took place on August 15, 1892 of James Hurst, 80 years old, of 30 Taunton Street. He was buried in grave plot B1641.

![20240807_143421[4011]](https://radnorstreetcemetery.blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/20240807_1434214011.jpg)