It is seldom possible to read the words of our working-class ancestors, after all, what time was there to write diaries or even letters, but there is one source where occasionally we can hear their voice and that is in contemporary local newspapers.

In 1874 Richard Renwick Pattison retired from the Great Western Railway Company after a career spanning more than thirty years and the men with whom he had worked all that time had a whip round.

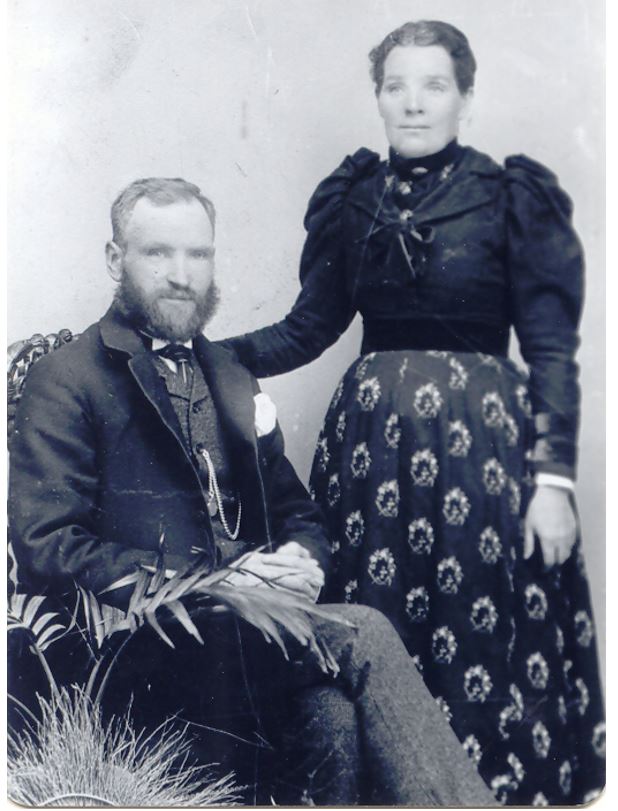

Richard Renwick Pattison was born in Houghton le Spring, Durham in 1819, the son of Christopher and Jane (Renwick) Pattison. He married Sarah Bellwood in Heighington, Durham on December 31, 1839 and by 1843 they had moved to Swindon, the new railway town in Wiltshire.

The GWR records state that Richard R. Pattison, engineer and fitter, was the third foreman of the Erecting Shops appointed in 1843 alongside Thomas Atkinson and Walter Mather. He is recorded as being a member of the team who erected the first engine built at the works, the “Premier,” completed in under two weeks in 1846 and later renamed the Great Western.

When Richard retired in 1874 the Swindon Advertiser covered his testimonial in some length:-

‘On Saturday week, the workmen employed in the B Shed, over which Mr. Pattison had been foreman, presented him with a silver inkstand and a very handsome writing desk, nearly all the men and lads in the department having contributed to the testimonial fund.

The subscribers and friends having been assembled in the B Shed, at the close of the day’s work, the desk and inkstand were duly presented to Mr Pattison by Mr Evans, accompanied by a few brief remarks expressive of the feelings which had dictated the offering, and hoping that the recipient of it might be spared to enjoy it, retaining always the good-will of those over whom for so many years he had acted as foreman.’

Richard then took to the floor and gave the following address:

‘I need not tell you how pleasing it is to my feelings to have this mark of respect shown to me on our separation, for it is really more than I could have expected, for I have done nothing more than to fulfil my duty as a foreman between master and man, and which duty I have endeavoured to fulfil impartially, and without favour. If I have in any way failed in this it has been an error in judgement. But, really, a foreman’s position is the most difficult to properly fulfil that I know of, for what with engines, masters, men, and those confounded boys – a toad under a harrow has a more comfortable life.

However, I may truly tell you all one thing, and that is, that I have never made one favourite in the shop, and those amongst you who have been promoted or raised one step higher up the ladder, have been promoted entirely through your own merit; at least so far as my judgement and conscience enabled me to judge fairly between you. And I am proud to say that there is not a shop in the kingdom that can surpass us for steady good workmen.

Another thing I should like to refer to, and it is this; we have had less change of men than in any other shop, and I sincerely hope this state of things will continue. And I have every reason to believe it will, for I have no doubt my successor will do all he can to pursue the same path; and I hope this splendid testimonial will be an inducement to him so to act, that should the day come when he shall be enabled to retired from his work, he also may receive a similar reward or mark of respect.

Now, fellow workmen, let me once more seriously thank you for this splendid testimonial and mark of respect which I shall highly prize, and which I hope may be handed down by my children for generations to come. But before we part I should like to ask one favour of you all, and that is forgiveness for past hard words, which perhaps was my greatest sin. But then, when you had the word you had the worst. There was no after sting or malice, for that is a thing unknown to me; and I am pleased to be able to say that I take farewell of you all with the best and kindest feelings and wishes, and I assure you I feel the separation more than I can express.’

That same evening the members of the testimonial committee entertained Richard at the Queen’s Arms Hotel. Following a toast to his health Richard spoke a few words, reminiscing on his time in the Works, saying ‘there were one or two things he should like to refer to, because they formed the foundation of his success.’ He went on to say that he had always kept his time in the works and that he could honestly say that for the first two years of his being at New Swindon he never lost ten minutes, and when, after he had been there about three years he lost his first quarter, he thought it would have broken his heart. He and a companion were talking and did not hear the bell ring, and this put him behind, and he could assure them he had never forgotten the circumstance.

He continued – another thing was this: whenever he had a pound he put it by – he put it in a building society, and in fourteen years it became two. This was a point he had always carried out: whenever he could save a pound he saved it, and when he had once saved a pound he never afterwards spent it, but left I to make more.’

The Works foremen had huge power and influence and were not the best loved of colleagues, but it would seem that Richard Pattison might have been of a different mould, for he received not just one, but two testimonials.

‘On Saturday afternoon last, after the day’s work in the shop, the boiler makers employed in the same department, but under another foreman, presented Mr Pattison with another testimonial, consisting of a silver goblet, and a pair of gold eye glasses.’

Again, we have the opportunity to read the words of Richard:

‘Mr Amos, Mr Sharps, and fellow workmen: This mark of respect is truly more than I could expect of you, for it is no secret that we have been continually at war with each other – my shop against the boilersmiths’ shop. But then it was only a friendly war in our effort to get the company’s work forward. You all know that your esteemed foreman (Mr Sharps), always liked to steal a march over the fitters, and then he quietly enjoyed a laugh at us. But then, we not unfrequently had our laugh at the blessed boilermakers. However, it is very gratifying to find that in our struggle to get the company’s work done we have preserved good fellowship, which is due in a great measure to your good and valuable foreman, Mr Sharps, whom you ought all to esteem, for he is truly a good man.

Now, my friends, you will not expect a long speech from me, but I must again express my sincere thanks for this splendid testimonial and mark of respect, and I wish the goblet had been full of wine so that I might have drunk all your healths. However, I hope you will all have an opportunity of drinking out of it yet, for I hope to have many a quaff from it in memory of bye gone days in the B shop, and of my kind friends there. (Loud and long continued cheering).’

Sadly, after so many years hard work, Richard Pattison did not enjoy a long retirement. He died aged 60 at his home in Sheppard Street on December 4, 1879 and was buried in the churchyard at St Mark’s.