Mark Sutton had a life long interest in the Swindon men who served in the Great War, researching, writing and recording their service and sacrifice in his book – Tell Them of Us.

Mark made numerous visits to the battlefield cemeteries in France and Belgium, laying wreaths on the graves of Swindon men on behalf of their families back home. Mark also worked with Swindon’s schools, showing items from his vast military collection. He knew instinctively how to talk to children about a war that was beyond living memory but intrinsic to our town’s history. For many years he conducted guided walks at Radnor Street Cemetery, visiting the Commonwealth War Graves and remembering the men buried there. He was a popular speaker on the Swindon history circuit, his talks selling out immediately they were announced. He was also co-founder of Swindon Heritage, a quarterly history magazine published between 2013 and 2017. Sadly, Mark died in 2022 but his memory and his legacy will live on, in the same way he made the story of Swindon’s sons who served in the Great War endure.

I begin with the story of Arthur North who is mentioned in Mark’s book Tell Them of Us and is told here in the words of Kevin Leakey, local historian researching the history of Queenstown and Broadgreen.

Arthur was a younger brother of one of my Great Grandmothers – Kate Leakey.

He was 7 months old and living with his family at 62 Bright St. on the

1891 census, so I would guess he was probably born at that address.

By the 1901 census the North family were living at 69 Cricklade Rd and

by 1911, were at 139 Cricklade Rd, where Arthur’s parents lived until

they passed away.

The 1934 funeral of his Mother, Mary Ann, took place at Trinity

Methodist Church (139 Cricklade Rd being a few doors away from the

church), which I think was the church the WW1 memorial came from.

Arthur emigrated to Australia in 1909 and worked as a farmer, living

with his Uncle Samuel North and his family at a small place called

Batchica near Warracknabeal, Victoria.

He joined the Australian Army in January 1915, and after going to

Gallipoli in Sept. 1915, he seems to have been ill from the end of

October until June 1916, then spending the next 7 months in the UK,

before being sent to France in Feb. 1917.

He was killed on the 3rd May 1917 on first day of the second battle of

Bullecourt. As far as I can tell his body was never recovered.

The Red Cross files give info about his death from other soldiers that

saw him on the day it happened. I don’t suppose it was at all unusual, with the men being in the middle of a battle at the time of his death, but their reports as to his

whereabouts etc. seem to contradict each other.

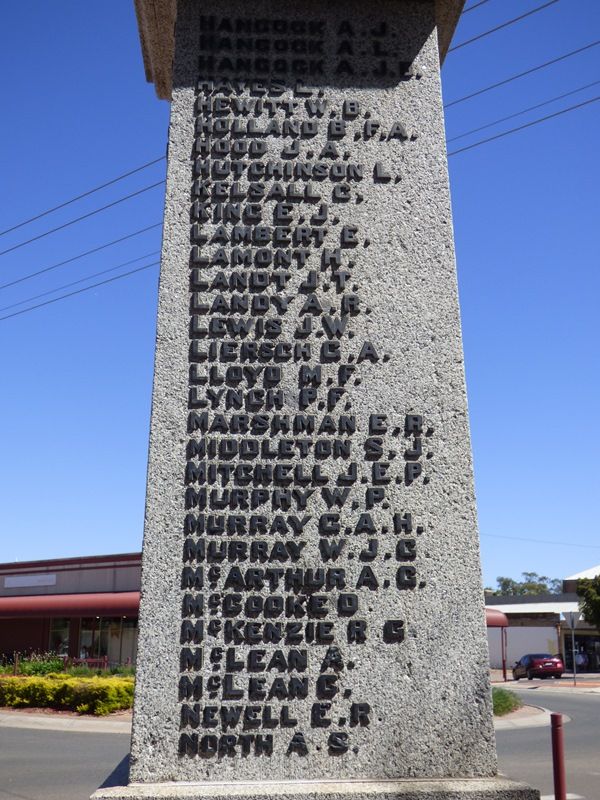

Apart from his name being on the Gorse Hill memorial, it is also on the

Warracknabeal war memorial in Australia.

Sadly, we have no photos of Arthur and aren’t in contact with any of his

brothers and sisters families, but I always put a cross down at the

cenotaph every year in remembrance.