I had long wanted to find the grave of Mary E. Slade who died in 1960. I eventually discovered she was buried in the churchyard at Christ Church, but where …

The Swindon Committee for the Provision of Comforts for the Wiltshire Regiment was formed in 1914. More than thirty years later Mary Slade and Kate Handley would still be supporting the soldiers who had survived the horrors of the Great War and the families of those who hadn’t.

Mary Elizabeth Slade was born in Bradford upon Avon in 1872, the daughter of woollen weavers Frank and Susan Slade. Mary and her brother George grew up in Trowbridge but by 1899 Mary had moved to Swindon and a teaching position at King William Street School.

At the outbreak of war Mary headed the team of mainly women volunteers who were based at the Town Hall. Their work was much more than despatching a few cigarettes and a pair of socks to the Tommies on the Front Line and soon became a matter of life and death as the plight of the prisoners of war was revealed.

“When letters began to arrive from the men themselves begging for bread, it was soon realised that they were in dire need, and in imminent risk of dying from starvation, exposure and disease,” W. D. Bavin wrote in his seminal book Swindon’s War Record published in 1922.

The provisions the prisoners received daily was a slice of dry bread for breakfast and tea and a bowl of cabbage soup for dinner.

“Had it not been for the parcels received out there from Great Britain we should have starved,” said returning serviceman T. Saddler.

The team of volunteers co-ordinated supplies and materials with the support of local shopkeepers, schools and hard pressed Swindon families.

In the beginning the committee spent £2 a week on groceries to be sent to Gottingen and other camps where a large number of men from the Wiltshire Regiment had been interned following their capture in 1914. By October 1915 the committee was sending parcels to 660 men, including 332 at Gottingen and 152 at Munster. And at the end of July 1916 they had despatched 1,365 parcels of groceries, 1,419 of bread comprising 4,741 loaves, 38 parcels of clothing and 15 of books.

As the men were moved from prison camps on labour details, the committee adopted a system of sending parcels individually addressed. Each prisoner received a parcel once every seven weeks containing seven shillings worth of food. More than 3,750 individual parcels were despatched in the five months to the end of November 1916.

But their work did not end with the armistice on November 11, 1918. Sadly, the soldiers did not return to a land fit for heroes as promised, but to unemployment and poverty. Mary Slade continued to fund raise for these Swindon families through to the end of the Second World War.

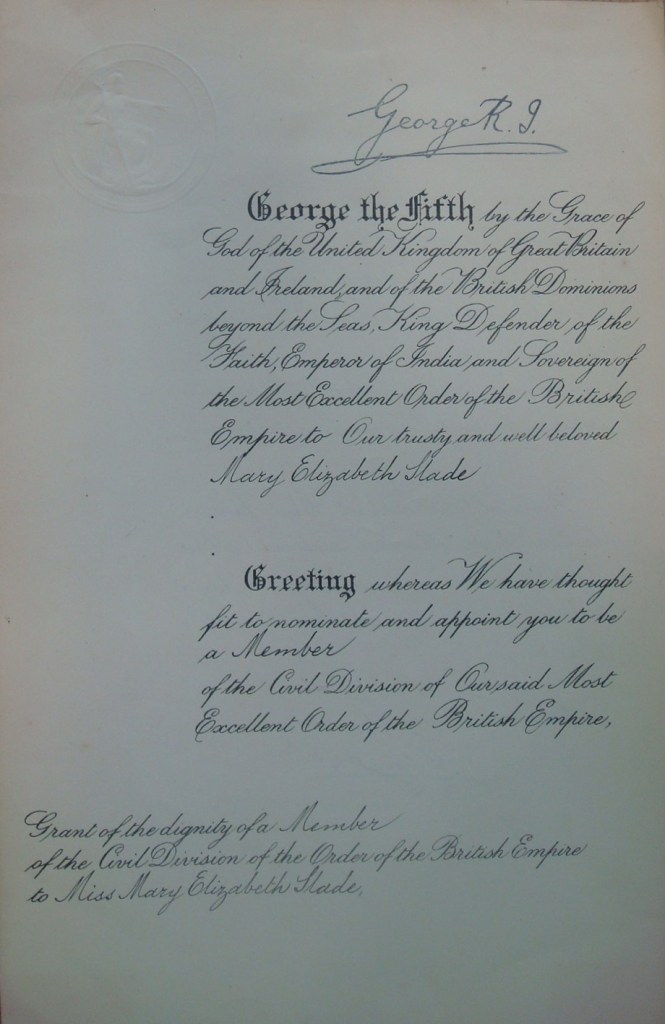

On July 25, 1919 Mary Slade and Kate Handley represented the Swindon Prisoners of War Committee at a Buckingham Palace Garden Party and in 1920 Mary was awarded the MBE.

Mary Slade died suddenly on January 31, 1960 at her home, 63 Avenue Road. She was 87 years old. The previous evening she had been a guest at the choir boy’s party at Christ Church.

Yesterday Noel and I visited the churchyard at Christ Church to pay our respects at the grave of our friend Mark Sutton. As we passed the Rose Garden on our way out I looked down and there was a plaque dedicated to Mary E. Slade. It was through Mark’s lifelong study of the Swindon men who served in the First World War that I first heard the story of Mary E. Slade.

Mary Elizabeth Slade

Mary Slade and Kate Handley