At 13 years and 8 months of age William was working as a ‘slipper.’ A ‘slipper’ was a young lad who assisted with the movement of wagons by horses. He would place the chocks to ensure that the wagon did not move when parked. They were called slippers because the chock looked like a slipper.* As one of the jurymen remarked during the inquest – ‘he thought it a great shame that the Co. should employ lads at such work. It was very dangerous for the lads so employed.’

William Hall had a short life. You could easily miss him on the 1881 census returns where he is recorded as James William Hall aged 4 years old. He was then living in Llanelly, Carmarthenshire with his parents John and Ellen, and two brothers. William was born in Swindon in 1877 but by 1881 the family had lived in Wales for a few years. His younger brother Thomas was born in 1879 in Llantrisant while Frederick was born in Llanelly in 1883. By 1890 the family were back in Swindon living at 166 Rodbourne Road, handy for the Works where John worked as a Stationery Engine man and where William would soon join him.

The Fatal Accident at the GWR Station

On Saturday, Mr W.E.N. Browne, coroner, held an inquest at the Cricketers’ Arms, New Swindon, on the body of the lad William Hall who received fatal injuries at the GWR Station, New Swindon, on the previous Thursday. Mr T. Wheeler was chosen foreman of the jury, who then proceeded to view the body, which was lying at the GWR Medical Fund Society Hospital. Inspector Wheeler was present to watch the proceedings on behalf of the GWR Co. The following evidence was taken:-

John Hall sworn, said: I am father of deceased, whose age was 13 years and 8 months. He had been only two days in the employ of the GWR Co., but he was at the same work for three days a fortnight ago, but left and did nothing till he was taken on again during the past week.

Henry Roach, shunter, in the Loco. Dept., said he was standing near the E Box in the afternoon. He heard someone call out, and on looking round he saw the second wheel of the van go over the deceased. Witness went to the lad’s assistance and picked him up. He asked deceased how he got under the van, and he replied, “My foot caught in the points, and it threw me down.” Deceased was quite sensible when picked up. The driver was at the horse’s head.

By a juryman: – It was a general practice for boys to be employed in “slipping coaches.”

(A juryman here interposed with the remark that he thought it a great shame that the Co. should employ lads at such work. It was very dangerous for the lads so employed).

Albert James Ford, said he was a driver in the employ of the Great Western Railway Company. Deceased was working with him as a “slipper.” On the day of the accident he was at work with the deceased, as usual. The first he heard of the accident was when the boy, being caught under the wheel, cried out. He went to the lad, and found the wheel had passed over him, and his shoe was left in the points. It was a horse box that was being drawn, but the boy was not riding on it at all. Witness had that same morning cautioned the deceased against walking on the rails, and he was not doing so when the accident happened. If the lad’s foot had not caught in the points the accident would not have occurred.

Mr Cailey, assistant to Messrs Swinhoe, Bromley, & Howse, said deceased was admitted to the hospital about 2.30 p.m. on Thursday. He was suffering from severe injury to the thigh and one arm. Deceased had his boots on when brought to the hospital. He lingered till six o’clock, when he died from exhaustion.

The Coroner having briefly summed up, the jury returned a verdict of “Accidental death.”

The Swindon Advertiser, Saturday, Feb. 15, 1890.

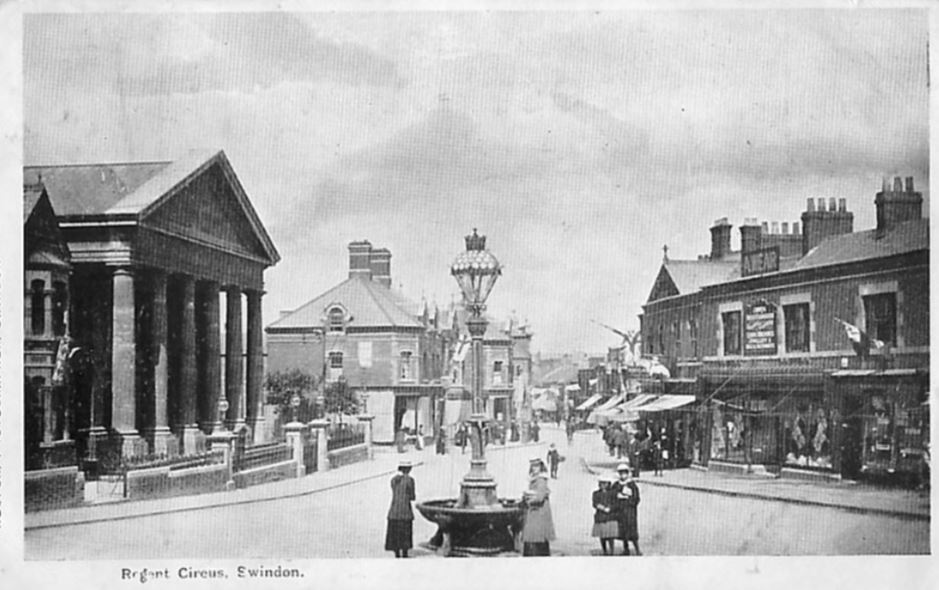

c1886 View of Swindon GWR Works from railway line published courtesy of Local Studies, Swindon Central Library.

Today there is no one left to remember the young boy who was doing the work of a man. No one to remember that William Hall was 13 years and eight months old when he was killed at work.

William was buried on February 18, 1890 in grave plot B1778 – a public grave that he shares with two others.

*Many thanks to David Robert for correcting a previous error.