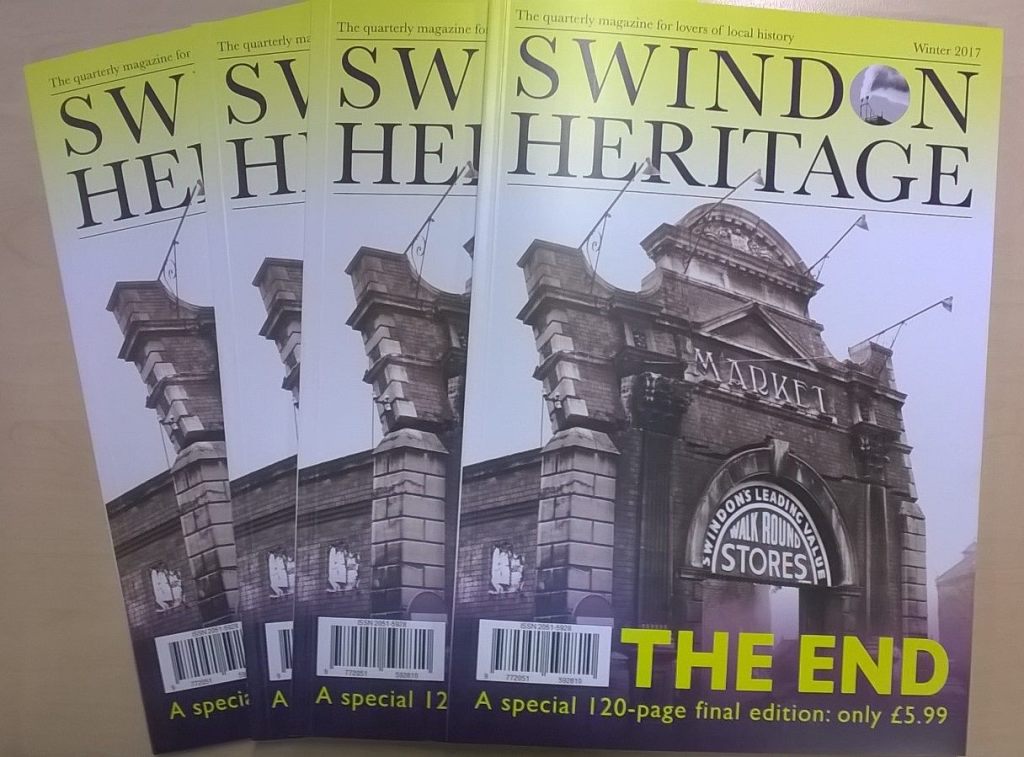

This article was written by Graham Carter, Swindon Advertiser columnist, and published in the Autumn 2016 edition of the Swindon Heritage Magazine.

Grandpa, the man who saved the Medical Fund

Swindon’s GWR Medical Fund was famously a blueprint for the National Health Service when it was introduced in 1948, but what is often overlooked is the crisis that seemed destined to destroy the organisation during the First World War.

And while the name of George W. Brunger isn’t often remembered as one of the visionaries of a railway town with a health service more than a century ahead of its time, as chairman for 29 years and its last, then he deserves a special place in Swindon’s history.

And George’s granddaughter, Maggie, along with her elder brother Alan, who spent hours recording ‘Grandpa’s’ oral memoirs’ before his death in 1964, have been piecing together the family history.

It tells of how George, who had previously only been an ordinary member of the Medical Fund, stumbled on a crisis meeting at Milton Road Baths – now the Health Hydro – and took control of its destiny.

“Grandpa was returning home from a union meeting in London,” said Maggie. “After disembarking from the train in Swindon, he was walking home when he heard a commotion coming from the Medical Fund building, and decided to go in.”

Formed in 1847, the Medical Fund provided a comprehensive ‘cradle to grave’ service and operated its own hospital, but exactly a century ago, in the last weeks of 1916 faced a huge dilemma because of the First World War.

Many local men were occupied with the Railway Works’ contribution to the war effort, George himself working as a fitter in AE Shop, making heaving guns. But many of the town’s men were away on active service, so subscriptions were critically low, and the crisis meeting was called to find solutions for an organisation that had exhausted its credit at the bank, so its cheques for doctors’ salaries were bouncing.

With the management committee and members arguing over a proposal to increase subscription rates, the closure of the Medical Fund altogether was a very real prospect.

“Grandpa entered the meeting, which was in uproar, and pointed out that they would stay there all night and still not get anywhere. So he suggested that a special committee be appointed to investigate their problems, and report back to members.

“His motion was passed unanimously, with seven people nominated; and Grandpa was the seventh.”

After a few weeks’ deliberation, the special committee reported in February 1917, in a hall that was packed to overflowing.

Surprisingly, it recommended only a penny-a-week increase in subscriptions, rather than the threepence suggested by the management committee, whose view was backed up by the Medical Fund’s lawyer.

When the members overwhelmingly supported the penny plan, it was effectively a vote of no confidence in the management committee, and most of them resigned.

George felt obliged to stand for election to the new committee of 15, and after the man he proposed as chairman refused the post, he put himself forward, and was elected.

Then aged 35, he would remain chairman until the Medical Fund was dissolved to make way for the introduction of the National Health in 1948, apart from when he took a year off and was vice-chairman in 1924.

In interviews with his grandson, Alan, in later years, he revealed that many of the ideas adopted by the Medical Fund during his time as chairman were his own.

Aneurin Bevan, the Minister of Health who was in charge of introducing the NHS, naturally interviewed George during visits to see how the Swindon model worked, and they must have had discussions about the handling of doctors, which was a key issue when the NHS was eventually formed.

A major cause of the Medical Fund’s financial problems were the huge salaries commanded by the three senior doctors they employed who were based at Park House in the Railway Village. George’s novel solution was actually to increase the salaries of junior doctors, while slashing those of the senior ones, including Dr Swinhoe, at the top of the pyramid.

His dealings with the Medical Fund inevitably brought George into contact – but also conflict – with management.

As a humble fitter – his union activities prevented him from progressing up the managerial ladder – he found himself in meetings with the railway company’s Swindon top-brass, but stood his ground.

He was once ordered to remove his hat when meeting FW Hawksworth, but told the Chief Mechanical Engineer: “I haven’t come here to undress!”

George had come from humble beginnings, but showed himself to be a committed and fearless young man.

Born in Maidstone in 1881, when he was 17 he lied about his age, claiming to be 18, so he could enlist in the Royal Engineers.

He quickly found himself in South Africa with the outbreak of the Boer War, the following year, and, apart from a long spell recovering from dysentery, fought much of the campaign, receiving clasps on his medals from six key battles, including the reliefs of Mafeking and Ladysmith.

After the war he stayed in South Africa to work in the diamond-mining boom, but returned to Britain in 1906, and soon married a local Maidstone girl Lillian Price.

They were married on Boxing Day 1906, but instead of honeymooning, after the ceremony they took the train to Swindon to begin a new life.

Arriving at 9.30pm, with snow on the ground, they walked from the railway station to their lodgings in Rodbourne, with a canary in a cage among the wedding presents they carried with them.

They later set up a permanent home at 40 Kingshill Road.

Always a union man, and an official for the Amalgamated Engineering Union (now the AUEW), George was also one of the founders of the Labour Party in Swindon, and served the party on the Town Council from 1919 to 1932.

As Chairman of the Housing Sub-committee in 1922 he oversaw the building of Swindon’s first (and one of the country’s first) council housing estates, at Pinehurst.

Such was the demand for houses that the queue of people outside the Brungers’ home in Kingshill, applying directly to George to move them up the list, led to the family calling the front room ‘the office’.

“He would have been mayor,” said Maggie, who lives in the United States but has been on an extended visit to her home town. “But my grandmother, who was very retiring, wouldn’t have it.”

He retired from both the Railway Works and the Medical Fund in 1947.

Maggie was 16 when he died, and missed the funeral because she was taking O Level exams on the day. Remarkably, his death occurred the day after Maggie’s brother Alan left Swindon to emigrate to Canada.

“He was a lovely old man,” said Maggie. “And of course to me he was always an old man. He was not a big talker, but he was well respected.

“I remember his black leather boots, which he kept by the fireplace, his red hair and his big hands. Every time I go up the beautiful stairs in the Health Hydro, I like to think of him grasping the rails.”

These days the committee room where George presided is often empty, while the smaller of the building’s two swimming pools is also closed, perhaps permanently.

The building was once a jewel in Swindon’s crown, and says as much about the vision and approach of Swindon’s leaders in past times – men like George Brunger – as the Mechanics’ Institute.

With its washing baths, swimming baths and even Turkish and Russian baths, it represented arguably the best leisure facilities enjoyed by any British workers at the time, as well as the medical facilities and services also available to members of the Medical Fund and their families.

But the building faces an uncertain future, just as it did, exactly a century ago, when destiny brought George Brunger, with perfect timing, to its doors.

Graham Carter

George Brunger died at St Margaret’s Hospital in June 1964 and is buried in grave plot C956, which he shares with his wife Lillian who died in 1955.

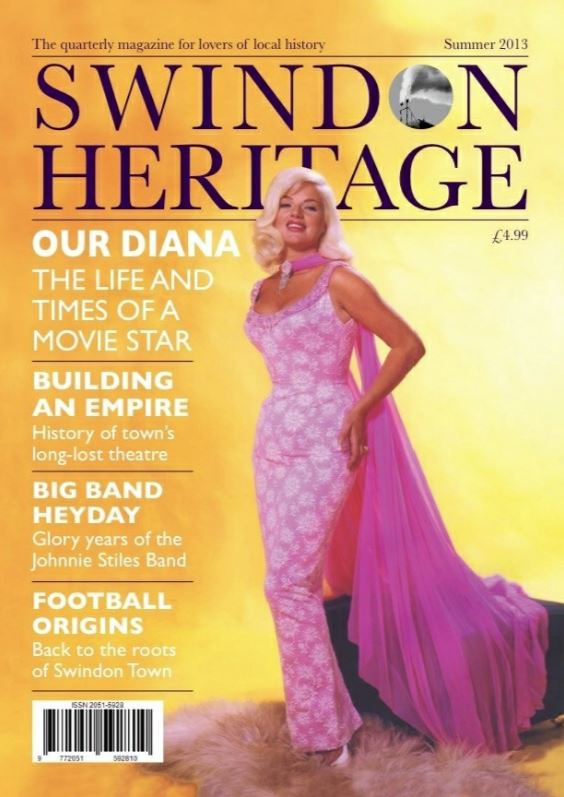

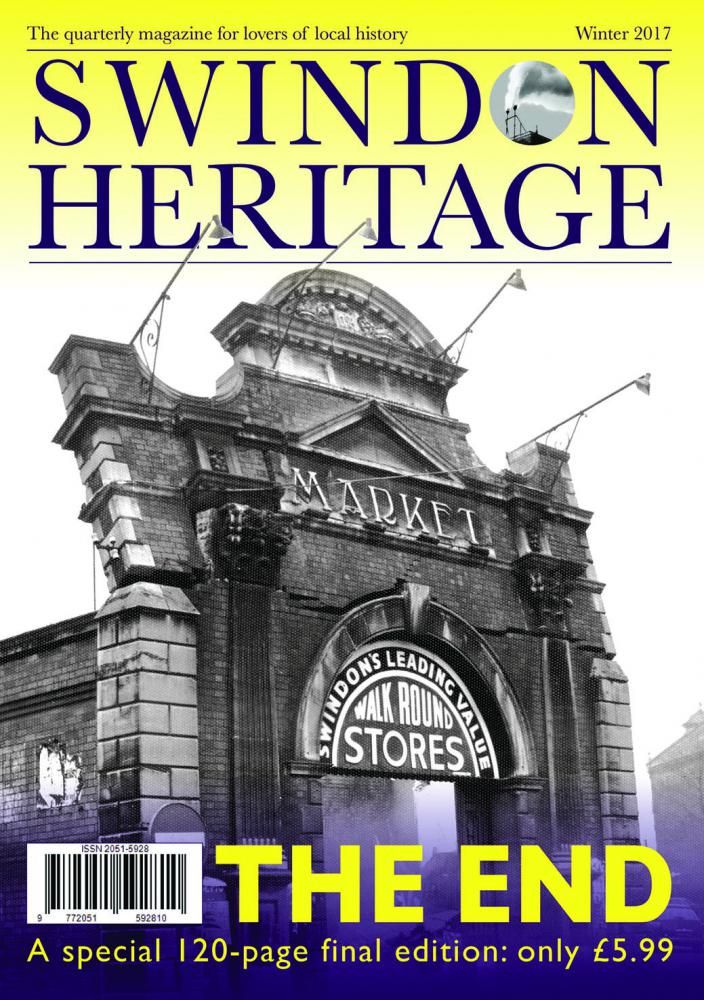

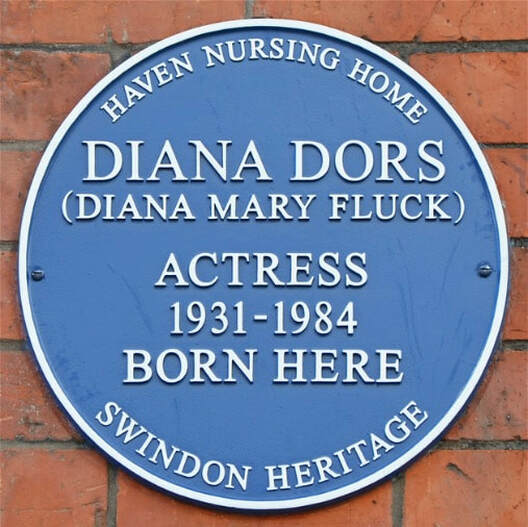

Swindon Heritage was a quarterly local history magazine co-founded by Graham Carter, the late Mark Sutton and myself and was published from 2013-2017. Back copies are still available at the Swindon Library Shop, Swindon Central Library and at the cemetery chapel during our guided walks.