And then there were those who came back – to a home fit for heroes.

Ernest Abraham Rivers was born in 1882 the second youngest child of James and Elizabeth Rivers’ large family. Ernest worked as a bricklayer and builder and married Eliza Painter on August 5, 1903. Eliza was born in 1882, the middle child of John Painter and his wife Hannah. Ernest and Eliza went on to have their own large family; their eldest son George Rivers (sometimes known as Painter) was born on October 13 1902, ten months before they married.

The family lived at 23 Prospect Hill when the 1911 census reveals they had five children, George 8, Raymond 7, Lancelot 5, Avis 3 and six months old Edna. They would go on to have another four children – Eileen born in 1913, Myrtle in 1915, Winifred in 1916 and Eric who was born in the summer of 1918.

On August 4, 1914 Britain declared war on Germany and at the end of 1915 Ernest joined the Royal Engineers leaving a wife and seven children behind in Swindon. Unfortunately, his service records are incomplete but it seems unlikely that he ever saw service overseas. Following his attestation he was sent to the army reserve before being mobilised to the Royal Engineers Depot W. Lancs. It was here that he served for 1 year 108 days before being discharged as no longer physically fit for War Service, suffering from a prolapse rectum, apparently a pre-existing condition that dated back to 1913.

Ernest returned to Swindon and his job as a bricklayer but in 1918 tragedy hit the family with the death of Eliza aged just 37. She left behind nine children including a baby just a few months old. There was no money for a private grave plot and Eliza was buried on November 13 in a public grave in Radnor Street Cemetery with four other unrelated people.

In 1939 war loomed large again. Ernest was living at 23 Prospect Hill with his two unmarried daughters. He had never remarried. That same year, youngest son Eric married Emily F. Gadd but sadly they would not have a happy ever after ending either. Gunner Eric Rivers, a member of the Field Rgt Royal Artillery, was killed on February 21, 1945. He was buried in Jonkerbos War Cemetery, Nijmegen Part 2, Belgium.

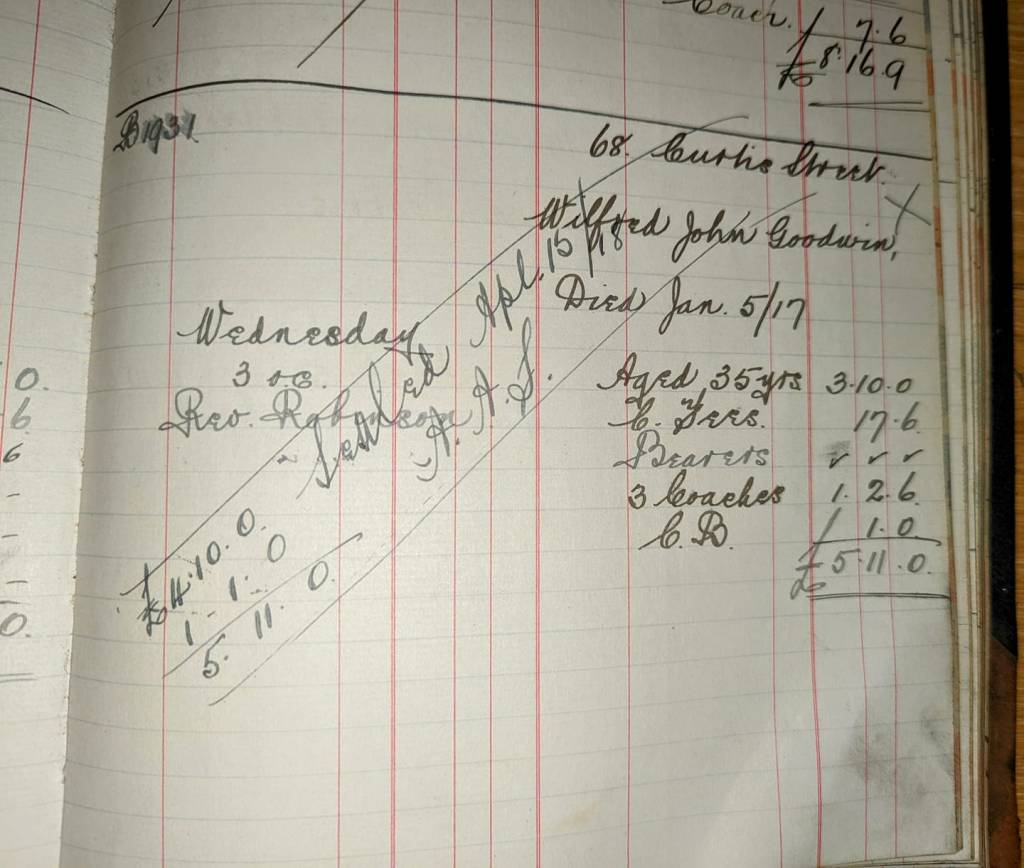

Ernest Abraham Rivers died in February 1951 aged 68. His last address was 23 Prospect Hill, the home he had shared with Eliza all those years ago. He was buried on February 24, 1951 in a public grave plot B1940, with four other unrelated people.

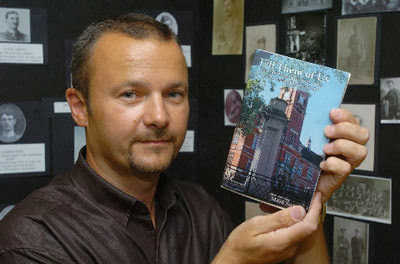

We continue to gather around the Cross of Sacrifice in Radnor Street Cemetery each Remembrance Day to remember those who sacrificed their lives in two world wars and those who died in more recent conflicts. And we remember those who returned but whose lives were never the same again – Tell Them of Us.