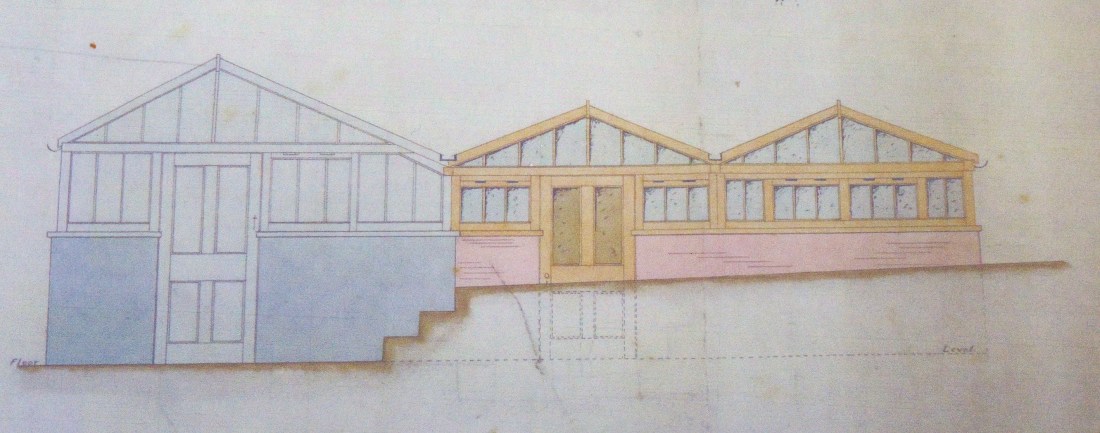

Back in the day there were flowers everywhere, right across the cemetery, displayed beneath glass domes; cultivated in the greenhouses. In 1907 the groundsmen were so busy that planning permission was sought for additional glasshouses to be built behind the caretakers lodge (see above illustration).

For those families who could not afford a headstone the flowers were a monument among the graves so densely arranged with barely a foot’s breadth between each plot.

Every grave was identified by a terracotta marker, sadly an unsatisfactory method. The system had worked well when a caretaker and gravediggers were employed in the busy cemetery but today they lie broken and scattered about. Some graves sport several of the brick like markers, others have none, and when searching for a grave they should be used with caution and only as a rough guide.

So what about the marker pictured here, found on a mound of earth. Is there a fallen headstone buried somewhere beneath? There are no clues, but it is possible to trace who was buried in plot D1083…

The facts …

The Radnor Street Cemetery burial registers reveal that there is only one person buried in plot D1083. His name was William John Molden, a boilermaker at the Works, who died on March 3, 1919 at his home, 145 Clifton Street. He was 44 years old and his funeral took place on March 8. Administration of William’s estate was awarded to his widow, Emily and his effects were valued at £179 5s.

Without applying for William’s death certificate we cannot ascertain his cause of death. Unfortunately we do not have a budget to pay for all the death certificates we need when researching the cemetery.

William was born on February 23, 1875 in Purton, the son of Eli and Hannah Molden. He began a six year boilermaking apprenticeship in the Works on February 23, 1890 aged 15. The 1891 census lists William as a 16 year old GWR Boiler Maker Apprentice living with his parents and older brother Sidney at Battle Well, Purton.

William married Emily Painter in 1898 and at the time of the 1901 census they were living at 65 Redcliffe Street, Rodbourne with their four month old daughter Dorothy.

The family appears on the 1911 census living at 122 Clifton Street where William lists his occupation as Boilermaker Rivetter. The couple have three children, Dorothy Maud aged 10, Muriel Louise Hetty, 8 and Harold Sydney John 2. Another son, Raymond Edward Joseph was born in 1917.

William was a relatively young man when he died. Perhaps he died as a result of the post-war ‘flu epidemic which raged through Swindon as it did everywhere else.

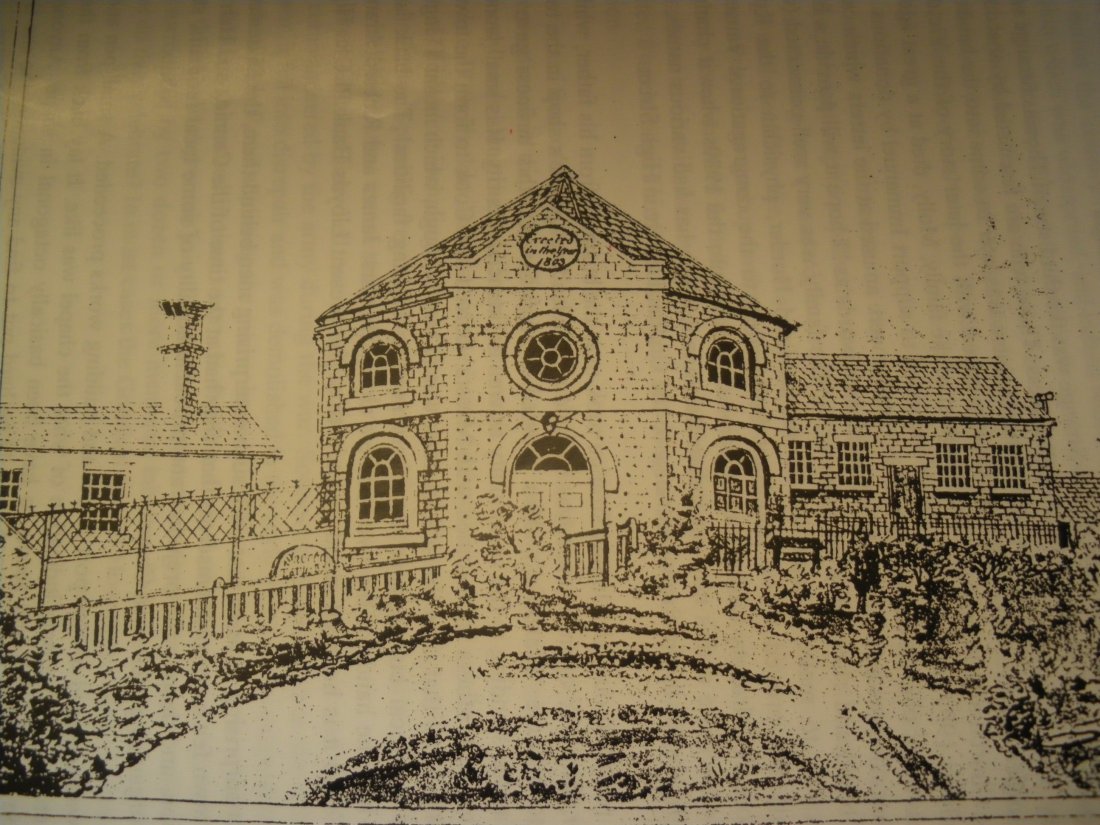

The Strange family were prominent non-conformists in the town and Martha’s father James founded the Congregational Church in Newport Street where members of the family were interred in the small burial ground. The Newport Street Church was demolished in 1866 but the burial ground remained intact for more than 15 years. However, in 1883 the graves of Richard Strange’s immediate family were exhumed for re-burial in Radnor Street Cemetery. The remains of his mother Mary who died in 1829, his father Richard who died in 1832 and his 16-year-old sister Sarah who died in 1820 along with those of Richard’s wife Martha who died in 1858 and a one-day old baby son also called Richard, were re-interred in plots E8463/4/5.

The Strange family were prominent non-conformists in the town and Martha’s father James founded the Congregational Church in Newport Street where members of the family were interred in the small burial ground. The Newport Street Church was demolished in 1866 but the burial ground remained intact for more than 15 years. However, in 1883 the graves of Richard Strange’s immediate family were exhumed for re-burial in Radnor Street Cemetery. The remains of his mother Mary who died in 1829, his father Richard who died in 1832 and his 16-year-old sister Sarah who died in 1820 along with those of Richard’s wife Martha who died in 1858 and a one-day old baby son also called Richard, were re-interred in plots E8463/4/5.