In previous years Andy and I have conducted the occasional guided churchyard walk at Christ Church. Built in 1851 the churchyard is the final resting place of many of Swindon’s Victorian entrepreneurs and, of course, the ordinary, working class people as well. Our much loved and sadly missed Radnor Street Cemetery colleague Mark Sutton rests here.

By the 1840s the medieval parish church of Holy Rood, close to the Goddard family home at The Lawn was proving inadequate to cater for the needs of the rapidly growing industrial Swindon.

A church had stood on the site since the end of the 12th century, possibly longer, but with the arrival in 1847 of an energetic young clergyman Rev. H.G. Baily came the impetus to build a new church.

Fashionable architect Gilbert Scott received the commission to design the new church hot on the heels of his success at St. Mark’s in the Railway Village.

The new church was built at a cost of £8,000, funding was originally sought through the Church Rate, a tax imposed on all householders whether or not they attended Church of England services. Unpopular, especially among non-conformists, this was eventually abandoned and the debt remained outstanding until 1884.

The consecration ceremony at Christ Church took place on November 7 1851 officiated by the Rt. Rev. Dr. Ollivant, Bishop of Llandaff, a mere 17 months after the foundation stone was laid on land at the top of Cricklade Street donated by Ambrose Goddard.

Pew listings for the newly opened church record that Ambrose Lethbridge Goddard paid for the first two pews on the south side of the Nave to seat twelve family members and another nine sittings in the South Transept for his servants.

The Goddard family are remembered in many of the fixtures and fittings in the church. In 1891 the reredos (panelling behind the altar) was presented by Pleydell and Jessie Goddard in memory of their brother Ambrose Ayshford Goddard. In 1906 the brother and sister dedicated the pulpit to the memory of their parents while the previous year Edward Hesketh Goddard presented the font in memory of his wife.

Despite the grandeur of the building, the people of Swindon preferred their order of service to be plain and simple. While Rev. J.M.G. Ponsonby battled to maintain unpopular High Church ritual at St. Mark’s, at Christ Church there was an absence of all pomp. Documents reveal that there was no surpliced choir, that altar lights were never used and that the preacher dressed in a black gown.

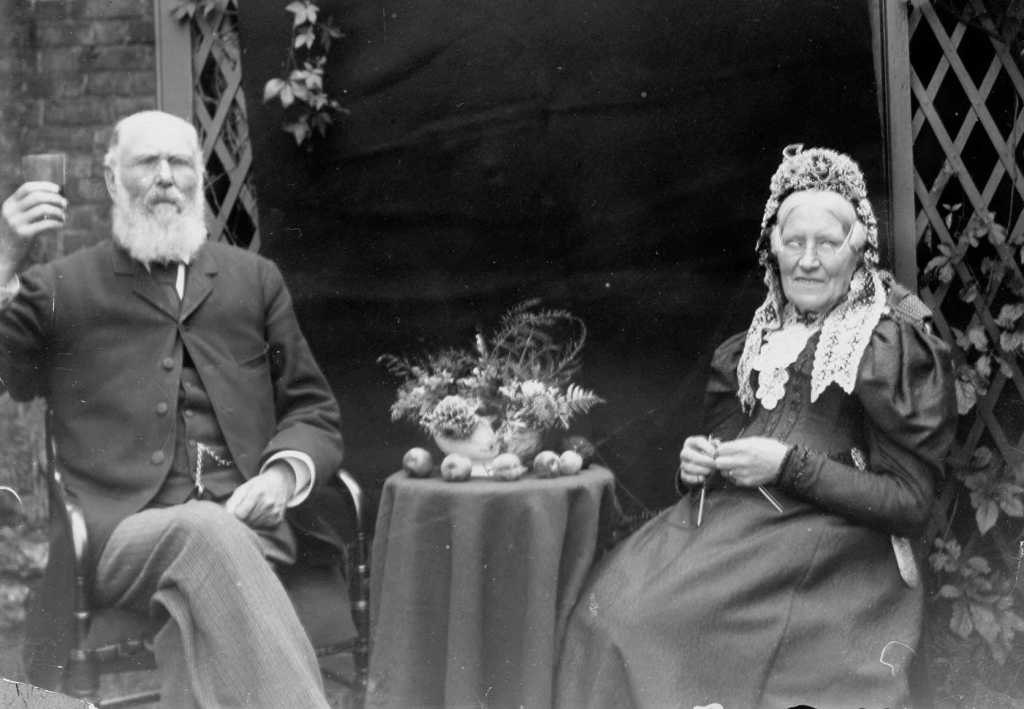

Builder Thomas Turner and his wife Mary. The Turner home is now the site of Queen’s Park.

The Toomer family memorial. The Toomer family home was the former Swindon Museum and Art Gallery in Bath Road.

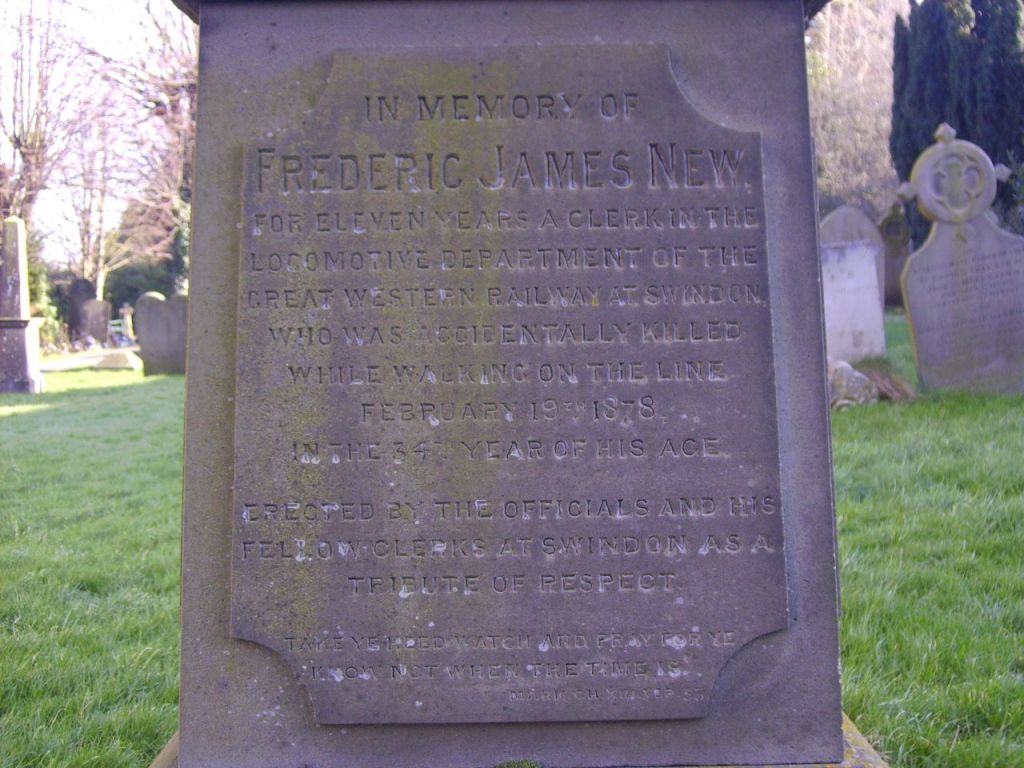

This is the New family memorial. Swindon school teacher Edith Bessie New moved to London and joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) becoming an active, militant Suffragette, continuing a personal campaign for women’s rights throughout her lifetime. She is buried in the cemetery at her last home Polperro, Cornwall.

The Morris family memorial. William Morris was the founder of the Swindon Advertiser.