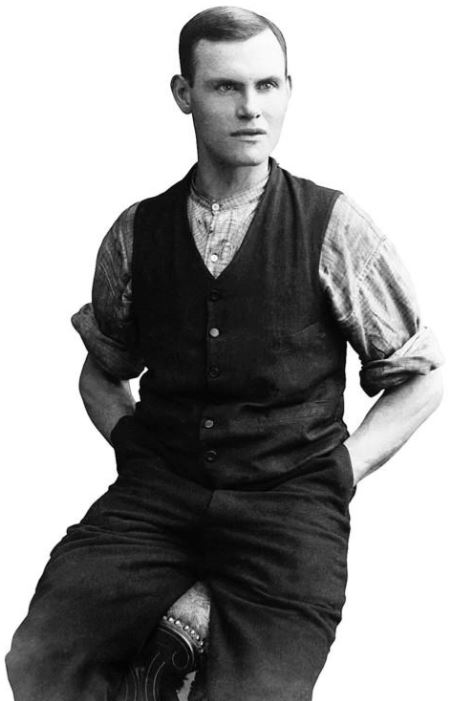

When William ‘Wally’ Richardson died suddenly in 1911 he was known to have a collection of football memorabilia including his own medals and team photographs of Swindon Town FC. Wally’s football career as left back with Swindon Town began in 1890/1 and spanned the teams’ transition from an amateur club to a professional one in 1894/5.

William ‘Wally’ Richardson was born in Edinburgh in 1869 and came to Swindon in around August 1889 – not as a professional footballer but as an engine fitter and a job in the GWR Works. At the time of the 1891 census he was lodging with Charles E. Chappell and his family at 17 Marlborough Street and was already playing with the Swindon team.

The 1911 census taken shortly before Wally’s death records him living at 8 Marlborough Street with his wife Kate. The couple had been married for 20 years. Sadly, two of their three children had died in childhood.

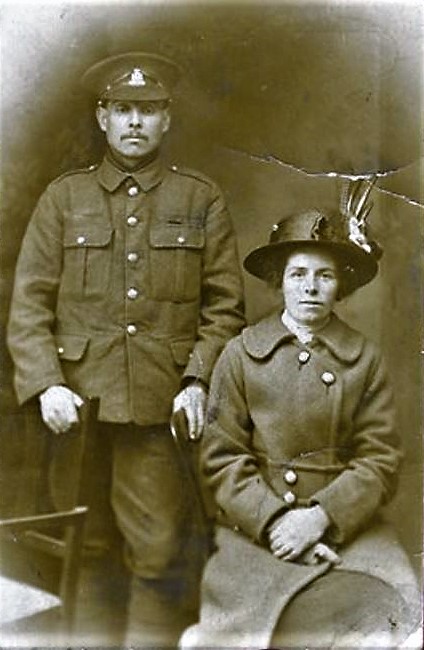

Photograph published courtesy of Swindon Town FC

Death of Mr. W. Richardson

A Well-Known Local Footballer

Funeral on Wednesday

On Wednesday afternoon the mortal remains of the late Mr William Richardson, who was a popular member pf the Swindon Town F.C. in the old amateur days, and for the first few seasons after the Club embraced professionalism, were interred at the Swindon Cemetery amidst many tokens of sympathy and respect.

“Wally” Richardson, as he was known to his intimates, was by birth a Scotsman, and it was in his native City of Edinburgh that he served his apprenticeship as a fitter. Twenty two years ago last May he came South, and after working for the GWR Co. at Newton Abbot, until August of the same year, he was transferred to Swindon. As soon as he came to the railway town, Mr Richardson commenced playing for the Town Football Club, and very soon made himself indispensable to the team in the left full-back position. Wally Richardson’s first season with the Club commenced in 1890, and when the Club became a professional Club, he signed forms for them and continued playing for several seasons. It was exactly 19 years ago, last Easter that “Wally” went down to Warminster to play in a six-a-side contest for a silver shield. The Swindon party won the shield, and, if we remember rightly, the trophy was given to the Swindon Schools’ League to be played for annually by the boys. Mr. Richardson had a most interesting collection of photographs of Swindon football teams for various seasons, and the medals won in his favourite pastime. Everybody regarded “Wally” as an excellent sportsman in the best sense of the word, and his rather sudden death on Saturday, after an attack of dropsy, will be regretted by a large following of friends.

Extracts from the Swindon Advertiser Friday July 7, 1911.

William ‘Wally’ Richardson was buried on July 5, 1911 in plot E7317, a grave he shares with his daughter Daisy who died in 1903.