Several years ago I joined an ‘expedition’ to discover the abandoned churchyard at Eysey and of course, as invariably happens when I start researching, I found a link to the parish of Lydiard Tregoze. Not this time to the St. John family and Lydiard Park, but the Willis farming family.

The medieval settlements of Eysey and Water Eaton were transferred to the parish of Latton, Cricklade in 1896 when they were by then just a few scattered cottages and farmsteads. The population of Eysey had always been a small one, just 95 adults in 1851 and only 52 in 1901.

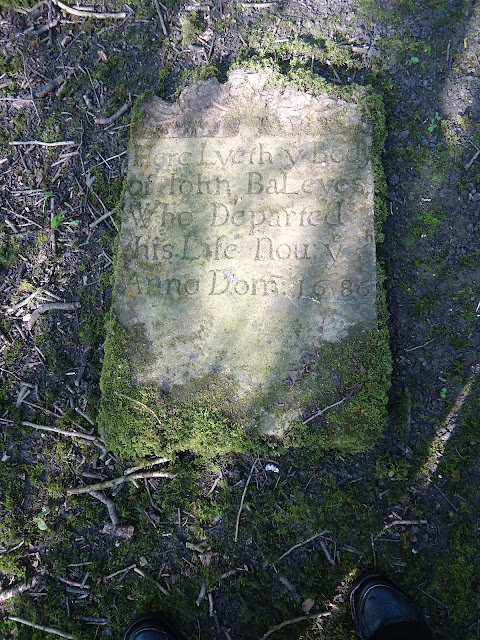

The church of St Mary’s, Eysey dated from the 14th century but was demolished and rebuilt in 1844. The Victorian church that replaced it stood empty for several years before it too was demolished in 1953. The parish registers date from 1571, and end in 1947 so as you can imagine there are a fair few burials in the churchyard. Today there is evidence of the boundary wall and some memorials but the whole area is heavily wooded and overgrown.

Amongst the nettles and fallen trees I found two perfectly preserved pink granite memorials both apparently dating from the 1920s and contained in a large family plot.

The inscription on one of the graves reads: In Loving Memory of Nelly, the dearly beloved wife of Henry John Horton who died at Eysey Manor Dec. 5th 1924 aged 55 years. On the other side of the memorial the inscription reads: Also In Loving Memory of Henry John Horton her beloved husband who died Sept 1st 1924 aged 64 years. The third inscription reads: In loving memory of Charles James Horton a loving brother & uncle who passed away Jan. 24th 1947, Aged 79 years.

In the neighbouring grave is a memorial to a mother and son. The inscription reads: In loving memory of Margaret the dearly beloved wife of Ernest Willis who died 24th July 1958. Aged 95 years.

On the opposite side of the memorial was the inscription that would lead me to Lydiard Tregoze.

In Loving Memory of Ernest Willis dearly beloved younger son of Ernest and Margaret Willis late of Can Court Wilts. July 5th 1891 – Feby 17th 1924 He served in the King’s Own (Royal Lancaster) Regt. & Royal Air Force throughout the Great War.

The Horton family had nipped back and forth across the Wiltshire/Gloucestershire county borders, farming at various times at the Manor Farm, Inglesham, Wiltshire and Broadway Farm at Down Ampney in Gloucestershire.

The Willis family had moved from Stanford in Berkshire to the parish of Lydiard Tregoze where John Ambrose Willis married farmer’s daughter Harriet Ellison and raised a large family at Can Court Farm, owned by The Masters, Fellows, Scholars of Pembroke College, Oxford. (For a history of Can Court Farm you might like to visit).

John Ambrose Willis died in 1886 and is buried in the churchyard at St Mary’s, Lydiard Tregoze. His son Ernest took over the tenancy of the farm and in 1889 married Margaret Fanny Horton at Down Ampney parish church where a host of Horton’s are recorded as witnesses at the wedding. That same year Ernest’s sister Ellen Willis married Margaret’s brother Henry John Horton.

On census night in 1891 Ernest and Margaret Willis are recorded at Caln Court with their one year old son Edward Ambrose and Ernest’s brother Henry L. Willis who was visiting with his two children, Sarah and Robert.

Henry John and Ellen Willis are at Costow Farm, a neighbouring property across the parish boundary in Wroughton.

By 1901 the Willis family had moved to Caversham where Ernest worked as a ‘butcher & purveyor’ at 12 Church Street. The family were still living in Caversham at the time of the 1911 census. Ernest and Margaret had been married for 22 years. Still living at home was Edward Ambrose, their eldest son, who worked at a Clerk for the GWR, and their daughter Margaret Louisa. Younger son Ernest is not recorded with the rest of the family.

Ernest senior died the following year. He may be buried in the large family plot in Eysey, perhaps mentioned on the sunken kerbstone that surrounds the two large memorials.

In 1911 Henry John and Ellen were living at Eisey [Eysey] Manor where Ellen (Nelly) died in 1920 and Henry John four years later. Henry John left £43,648 17s 9d with probate granted to his brother Charles James Horton and his three sons Robert Willis Horton, Henry Horton and Charles Horton.

Margaret, meanwhile, moved to Swindon and a house in Westlecott Road. The son with whom she is buried died at the Sanatorium, Linford, Hampshire in 1924. On the eve of the Second World War Margaret was still living at Southwood, Westlecott Road with her bachelor brother Charles J. Horton. Charles died in 1947 and Margaret in 1958 aged 95.